On May 18, 2015, the very first day of breaking earth on a five-year excavation program, Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis, a husband-and-wife team at the University of Cincinnati, made a breakthrough, along with their team of 35 archaeologists and archaeology students.

Outside Pylos in Messenia, on the southwestern coast of Greece, they found the walls of an undisturbed grave beneath an olive grove surrounding the Mycenaean-era site of Nestor’s Palace. Ten days later, they realized it was the tomb an undisturbed Mycenaean tomb, now known as the grave of the Griffin Warrior. But stumbling on a very rare grave shaft and stirring a warrior from his slumber after 3,500 years was anything but luck. It was the fruit of Stocker and Davis’ 25 years of research and excavations.

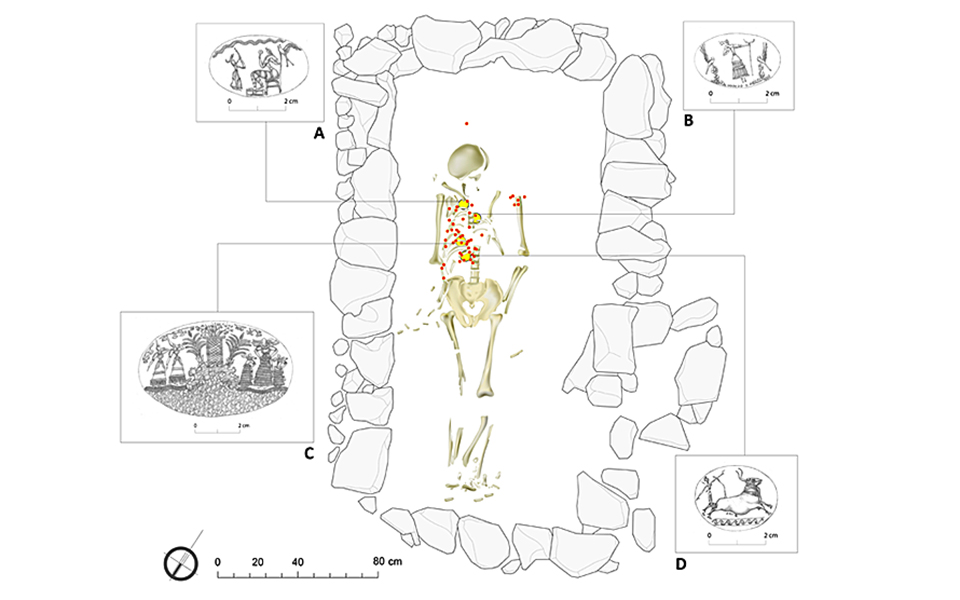

The grave, dated to 1450 BC, contained 1,800 artifacts, including spectacular weapons, ivory combs and four gold seal rings engraved with Minoan scenes.

“So many gold rings in one grave! Τhis was unusual and unexpected,” Stocker says.

At their first public presentation on the Griffin Warrior grave, which will be held tonight at the American School of Classical Studies of Athens (of which Davis was director from 2007 to 2012), the two archaeologists will focus on the four rings.

Before heading off to present their findings in Cambridge (October 10) and London (October 11), the archaeological couple spoke to Greece Is about the hard work that followed the excavation. Much of it was devoted to the very slow, painstaking, detailed and expensive process of conservation, which at times involved a piece of cotton on a souvlaki stick!

“The grave, dated to 1450 BC, contained 1,800 artifacts, including spectacular weapons, ivory combs and four gold seal rings engraved with Minoan scenes.”

The unearthing of the rings

“I can definitely recall the moment I found the gold rings. Jack had been saying for a while that he hoped we would find a ring, because signet rings are very special. He’d ask me about this every day and one day, there actually was one! The following day I found the outline of the second, which was very large and very complex. The other two came later and were a complete surprise,” recalls Stocker.

Andreas Karydas and Vicky Kantarelou of Demokritos, the Greek national scientific research center, who were working on the excavation, then used X-ray fluorescence (XRF) to determine the composition of the metals in the grave. This technique can determine the elemental composition of materials. “They analyzed the four gold rings and we now understand better their construction. They are not solid gold, and the pieces (the top, bottom and band) were manufactured separately and then joined. In some cases, the purity of gold is different for different parts.”

The engravings

“The workmanship and detail on all of the rings are incredible. They were likely manufactured by Minoan craftsmen in Crete and then brought to the mainland. The iconography is very significant because it offers new images of Minoan religion. One ring shows a female, probably a goddess, descending to the earth. She is holding a staff and is flanked by birds. Another shows a seated woman, probably a goddess, holding a mirror, and being approached by a smaller woman who is carrying an offering,” says Davis.

“On the largest ring, a group of three women appears to be dancing and the larger figure is perhaps a Minoan goddess. The smaller figures are likely young worshippers. In the other group, two women have their hands raised to their heads in what is called the “adoration gesture,” which is thought be a way to approach the goddess (rather like putting your hands together when you pray). All five women are approaching a shrine flanked by palm trees.” says Davis.

“The workmanship and detail on all of the rings are incredible. They were likely manufactured by Minoan craftsmen in Crete and then brought to the mainland. The iconography is very significant because it offers new images of Minoan religion.”

The restoration

Kathy Hall, senior conservator at the Institute for Aegean Prehistory Study Center for East Crete, made impressions of the design and undertook a preliminary cleaning. Then Wendy Reade did a more thorough cleaning after the XRF analysis.

“The process is very slow and painstaking because we do not want to leave any modern scratches on the surfaces. The conservators use cotton on souvlaki sticks dipped in ethanol or water for the cleaning so that no harmful chemicals will be left behind. Since gold does not tarnish or decompose, they are as beautiful now as they were during the life of the Griffin Warrior,” says Stocker.

The project involves significant costs, a major one being the salary and board of the conservators.

“This was a very focused project, so the cost was about 7,000 euros for 10 weeks”. We hope the rings will eventually be displayed in the Hora museum (near the site) along with the rest of the artifacts from Nestor’s Palace.”

“The process is very slow and painstaking because we do not want to leave any modern scratches on the surfaces. ”

Facing the warrior

This past summer, the two archaeologists excavated around the grave in order to determine how it was built. They expect to publish their results in a paper in January. They also removed the large stone and cleaned around it but didn’t find more artifacts.

“Lynne Schepartz, a human bone specialist at the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa, came to Pylos for a few weeks in February to help excavate the Griffin Warrior’s skull and pelvis region. Before that, we took them to Kalamata for X-ray. That was quite a production!” says Stocker.

“Schepartz’s colleague, Tobias Houlton, worked on a facial reconstruction so that we now have an idea how our warrior might have looked.”

The team has also made impressions of all the sealstones and had them illustrated by archaeological artist Tina Ross. The sealstones have also been photographed and are under study for publication. Christina Margariti, a textile conservator with the Greek Ministry of Culture, has performed some analysis of the fibers that were found in the grave to determine the type of cloth and how it was woven. “She recently sent the sample for dating, and we hope to have the results soon,” says Davis.

Now the team is preparing additional samples for dating that will hopefully be transported during the winter. They are also planning to apply for a permit for DNA analysis, which will hopefully be conducted in the spring.

Ηοpes and expectations

“Our hopes are to get people interested in the Griffin Warrior, the Mycenaean world, modern Messenia and Greece in general. We would like to attract more tourists to the archaeological site of Nestor’s Palace and the surrounding area. We also hope to raise funds to help with the cost of conservation, preservation and display. These will be ongoing for many years and the cost will be astronomical,” Stocker points out.

She is also trying to raise funds to purchase an X-ray machine, but these are very expensive.

“X-raying artifacts before conservation is a modern technique that allows one to see the surface of the artifact before cleaning. It makes decoration or writing visible before the conservator begins.”

“Our hopes are to get people interested in the Griffin Warrior, the Mycenaean world, modern Messenia and Greece in general.”