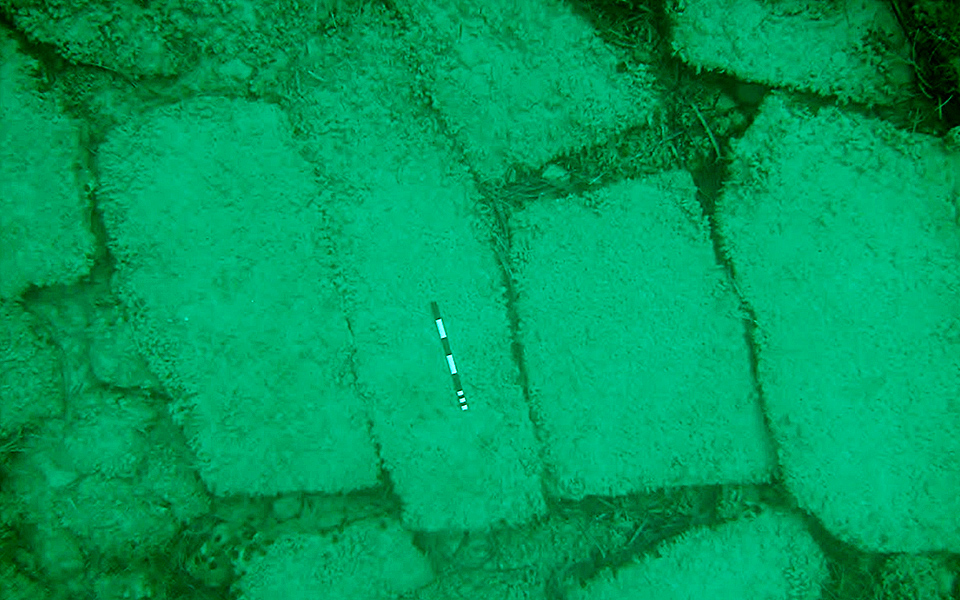

Greece’s seabed is known for its endless array of ancient treasures, so when some snorkelers swimming in Alikanas Bay in Zakynthos observed what looked like large circular colonnades, courtyards and paved floors – but mysteriously no pottery or other ruins indicating a former settlement – at a depth of around 2-5m, they were convinced they had discovered an ancient port city that had been lost to the sea.

The site was soon examined in situ by the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities of Greece, with Archaeologist Magda Athanasoula and diver Petros Tsampourakis, together with Professor Michael Stamatakis from the Department of Geology and Geoenvironment at the University of Athens (UoA).

This took place in 2012, when the Greek authorities initiated a scientific cooperation to examine the phenomenon together with The University of East Anglia (UEA). The research team went on to investigate in detail the mineral content and texture of the underwater formations in minute detail, using microscopy, X-ray and stable isotope techniques.

Working on the joint project, the universities have now determined that despite its startling resemblance to a man-made ancient city, the site is in fact made up of formations that have occurred naturally over the course of thousands of years.

“Despite its startling resemblance to a man-made ancient city, the site is in fact made up of formations that have occurred naturally over the course of thousands of years. ”

© University of Athens

“As geologists we are always excited to find out more about how the Earth works.” Professor Julian Andrews, from UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences, said. “I suppose a new archaeological discovery would have been seen as very, very exciting by everyone, but you can’t win them all!”

It has now been officially confirmed that the disk and doughnut morphology, which appeared like column bases, is typical of mineralization at hydrocarbon seeps. Professor Andrews said: “We found that the linear distribution of these doughnut-shaped concretions is likely the result of a subsurface fault which has not fully ruptured the surface of the sea bed.

“The fault allowed gases, particularly methane, to escape. Microbes in the sediment use the carbon in methane as fuel. Microbe-driven oxidation of the methane then changes the chemistry of the sediment, forming a kind of natural cement, known to geologists as concretion. In this case the cement was an unusual mineral called dolomite which rarely forms in seawater, but can be quite common in microbe-rich sediments. These concretions were then exhumed by erosion to be exposed on the seabed today.”

“This type of concretion is known all over the world from the Pacific to the North Sea and the Mediterranean,” Professor Andrews continued. “These ones are a bit unusual in that they are found in very shallow water. Most are found in hundreds or thousands of meters of water.”

“We found that the linear distribution of these doughnut-shaped concretions is likely the result of a subsurface fault which has not fully ruptured the surface of the sea bed”