Ιf you look at photographs of Athens from the first half of the 20th century, you’ll realize that of all the capital cities of the Western (at least) world, this is the one that has changed the most dramatically in the course of recent decades. For the worse.

The small town that extended around the rock of the Acropolis (and on top of it too, since during the Byzantine period the Parthenon was transformed into a church – Our Lady of Athens – while in Ottoman times a mosque held services between its columns), this Athens of 5,000 residents was proclaimed the capital of the newly established Greek state in 1833.

The young King Otto and his Bavarian functionaries, as well as those Greeks who embraced European aesthetics and perspectives, envisioned a city with neoclassical mansions and wide boulevards. The Royal Palace – which today houses the Parliament – was erected in the shadow of pointy Lycabettus Hill. Just down the road, Heinrich Schliemann – the excavator of Troy – built his mansion and named it Iliou Melathron (“Palace of Ilium.”) Along the same stretch of road, three emblematic sanctuaries of the spirit were founded: the University of Athens, the National Library and the Academy of Athens.

Queen Amalia expropriated 25 hectares of land next to the palace, imported trees and bushes from all over the world – even from the Antipodes – and created the Royal Garden so as to amuse herself during her endless hours of childless leisure. Very wealthy ethnic Greeks from Istanbul, Odessa and Alexandria offered hospitals, orphanages and educational institutions to the center of Hellenism.

By the end of the 19th century, Athens was home to 150,000 souls who worked in factories, ran small businesses or comprised the local elite as lawyers, doctors, owners of tanneries or beverage factories, and investors in the local stock exchange, which operated out of a coffee house and experienced its first crash in 1874, when shares in the Lavrio mines came tumbling down.

Today, metropolitan Athens begins at Elefsina and stretches all the way to the vineyards of Mesogeia. It covers the greater part of Attica and has a population of 3.5 million. One-third of the permanent residents of the country are settled here – composing a vast mosaic of city natives and first and second-generation immigrants, the middle-classes, the newly rich, but also once-comfortable-but-now-struggling families as well as people surviving on the fringes of poverty. No, there are no favelas in Athens. The despair of social exclusion does not prevail, even in the unplanned settlements around the capital’s enormous landfill; on the contrary, what is “breathing” is the expectation of a better life.

The population explosion in Athens began in 1922, following Kemal Ataturk’s rise to power in Turkey, when almost all of the Greeks in Asia Minor were uprooted. It peaked in the 1950s and 1960s, when the countryside – bloodstained from the Nazi occupation and the subsequent civil war – ousted its offspring en masse.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

In order to house the myriads of refugees and economic migrants, the face of the capital was literally swept away. The little two-story houses in the center of town and in neighborhoods were demolished. In their place rose five and six-story apartment buildings – each one stuck next to the other. As a rule, these were built using cheap materials and had no surrounding garden or parking space. Apart from the central avenues, the sidewalks and streets grew depressingly narrow. Piraeus came to join with Athens, as the farmland separating them – with its olive groves and fruit and vegetable plots – gave way to construction.

Most of the villages in Attica, where sheep grazed until the 1970s, were integrated into the urban structure. The Ilissos and the Iridanos, two of Athens’ three rivers celebrated in song, were covered over with asphalt, while the city’s dozens of streams – which kept the region cool but also attracted swarms of mosquitoes – were filled in. Even the slopes of the surrounding mountains – Ymittos, Penteli and Parnitha – were dug up and denuded of most of their forests.

A panoramic view of Athens today is an elegy to cement. From the balcony of my apartment, which is situated on an elevation in the center of town, I could count non-stop, from dawn to sunset, the white and gray matchboxes with television antennas and solar water heaters screwed into their flat rooftops. Here and there you see some groves, patches of green, or an opening where a square or hospital is located. In the distance, there is the enormous Ferris wheel of the largest amusement park in the city, and the lofty chimney of the Electric Company, which ceased to spew smoke years ago. When the visibility is really good, I can make out cruise ships heading into and out of Porto Leone – as Piraeus was once called – and even further away the mountainous masses of Aegina and the northern Peloponnese. Athens has only two skyscrapers, and these are relatively low at that, as a law forbids any buildings taller than the Acropolis to be constructed. I cannot see the Parthenon, however; three apartment buildings are enough to block my view.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Strolling through Athens, I remember images from my childhood, 40 years ago. And I am able to confirm the rapid, continuous transformation of the city.

I got to see my neighborhood, Kypseli, when it was still middle-class and bohemian. Over time, I saw its better-off residents steadily abandon it for the suburbs. Immigrants, mostly from Africa, then made it their home, opening Rastafarian hair salons, sitting on stools on the sidewalk in their colorful national dress. Then the Polish and Pontic Greeks came, the consumption of vodka soared and bakeries started selling piroshki. When the next wave came, of Arabs, the cafés started offering narghile.

The deep financial crisis that broke out in 2010 cast a pall over the colorful face of this multiculturalism. Almost half the shops closed; people milled about, unemployed, in the squares. During the winters of 2011 and 2012, many apartment buildings could not afford to buy heating oil for their furnaces; people burned whatever they could find in the hope of getting some warmth, and the atmosphere became suffocating.

Recently, Kypseli seems to – timidly – be making a recovery. Apartments are being renovated and rented through Airbnb. The metro station that – they promise – will be open sometime in the decade to come will signal a new, blossoming era.

As I walk through the center of Athens, I can say that my fellow citizens have certainly lost the ostentatiousness – the arrogance, almost – that the Greek belle epoque of the years 1995-2010 imparted to them, back when members of the middle class competed to see who among them could buy the most expensive cigars and who would go on vacation in the most exotic locales. But now they seem to be acquiring, slowly but steadily, an incomparably more substantive cosmopolitanism.

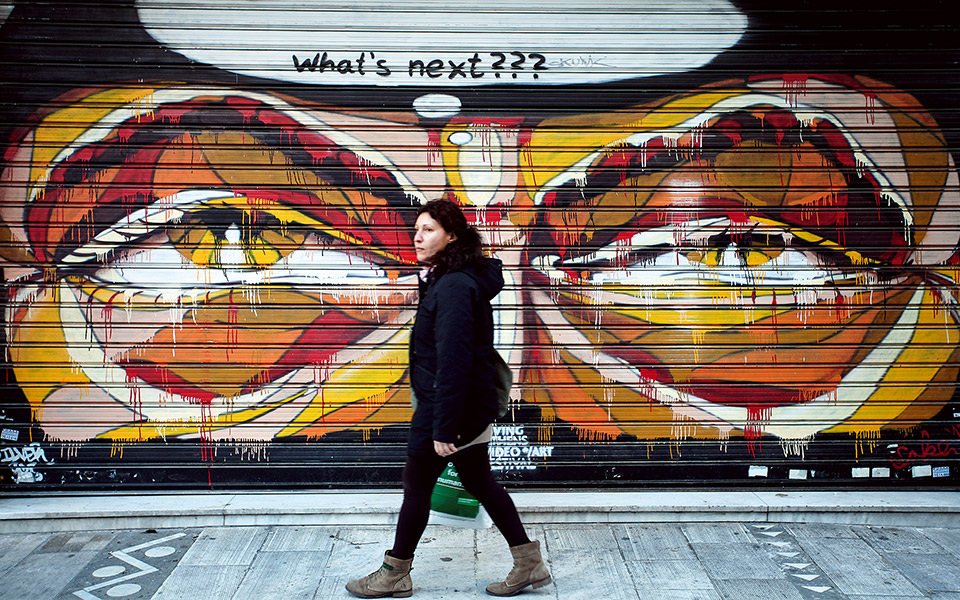

© Stephe Grape

Nowadays, few people’s eyes come to rest on a Chinese family – who you can tell are now permanently settled here by their shopping bags. Practically no one conceives of expressing displeasure at the sight of a homosexual couple – after all, impressive progress has been achieved recently in the recognition of the rights of the LGBT community. The magazine Shedia (Raft), published and distributed by homeless individuals, sells out quickly. The number of cyclists is increasing with impressive speed, as are the ethnic restaurants, alternative cafés and bars, as well as the apps that guide visitors around the sights of the city. A new generation, which swears by innovation, plays with technology at its fingertips and speaks English incomparably better than our prime minister, is barreling ahead.

Do not take me for someone exaggeratedly optimistic, however. A large percentage of Athenians in their most productive years, between 20 and 40, have emigrated, seeking work and prospects primarily in Western Europe. An even greater number – in the millions – are those who persist in reacting negatively, and even violently at times, to the cataclysmic changes of recent years and the tremors Greece has suffered and continues to endure. These people are nostalgic for a bloated state apparatus maintained by external borrowing and subsidies from the EU, for a closed society of civil servants and small landowners. The neo-fascist Golden Dawn party solidly ranks third in the polls.

Yet life gallops on and imposes its own terms. It is a matter of time until those most stubbornly nailed to the past adapt to the present and the future, in order to survive. Our emigrants will repatriate and – thanks to their international experiences – will provide a new vigor. Why? Because Athens is a magnet. No matter how far you travel, you will always be in orbit around it.

In order to evaluate people or places well, you must remember them not at their best, but at their worst. Athens, in the 50 years that I have known it, has gone through plenty of difficult – and even humiliating – phases. From 1967 to 1974, the military dictatorship strove to transform it into the capital of Greek Christian tackiness. During the decades of the 1990s and 2000s, pompous contractors and publicists aspired to fill it with malls, pushing it into a frenzied consumerism that made it look like Pompeii just before the catastrophe. In 2008, Athens was set alight by gangs, in a parody of a popular uprising. In 2011, the central squares were occupied by post-Peronists (who presented themselves as radical leftists) and by neo-fascists.

And yet, even at its worst, my city never for an instant lost its sun – that unique light it has that becomes relentless in the afternoons, consoling and caressive in the evenings, and hopeful in the mornings. It has never been deprived of its breeze, which rustles girls’ skirts, and carries even to its cement houses pollen from Ymittos and a salty tang from the Aegean. Or its sudden downpours, which wash the marble of dust and people of their delusions. Or its language – Homeric words spoken of late with both African and Asian accents. Or, finally, the feeling that it subjects you to: that you are at the same time transient and eternal, unnoticed in the crowd but simultaneously totally unique and impossible to duplicate. Whether with thorns or with flowers, Athens was and will be through the ages one big embrace.