Although their name implies there are only a dozen of them (“dodeka” being the Greek word for “twelve”), the Dodecanese Islands, a distinct archipelago in the southeastern Aegean, consist of fourteen main islands and numerous other isles, islets and prominent rock formations long familiar to Mediterranean seafarers. Located in the midst of the most important East-West sea lane in antiquity, the Dodecanese mark the crucial “corner” where, as the protective southern Anatolian coastline falls away on the starboard side, westbound sailing ships entering the Aegean had to turn and face (during optimal May-to-September sailing conditions) the full brunt of northern/northwestern winds, known as the Etesians or Meltemia. Time and again, these islands Dodecanese have played an important role in the history of the wider region.

© Visualhellas.gr, Ministry of Culture and Sports/Ephorate of Dodecanese

STRATEGIC OR REMOTE?

Rhodes, Karpathos and Kasos lie at the southeastern-most edge of the island group, with lonely Kastelorizo situated far away (127 km) to the east, just opposite the modern mainland Turkish port of Kas (ancient Antiphellus). Moving northwest from Rhodes, in consecutive geographical tiers, are Symi and Tilos; Nisyros and Astypalea; Kos; Kalymnos; Leros; the Lipsi (a sub-group of 27+ islets) and Patmos; and finally Agathonisi. Smaller islands and rocks to be found around these primary places include, respectively: Alimia/Alimnia, Chalki, Saria; Strongyli, Ro; Nimos; Syrna; Gyali, Pserimos, Telendos, Levitha, Mavros, Kinaros; Farmakonisi; the Arki (13 islets, including Marathi); and many more.

The sheer number of islands constituting the Dodecanese is almost inconceivable, but important to come to grips with, as both their profusion and location (the latter sometimes considered strategic, at other times remote) have greatly contributed to their frequent exploitation and occasional neglect through the eons, since Neolithic humans first disembarked on their shores.

© Visualhellas.gr

SWIMMING ELEPHANTS

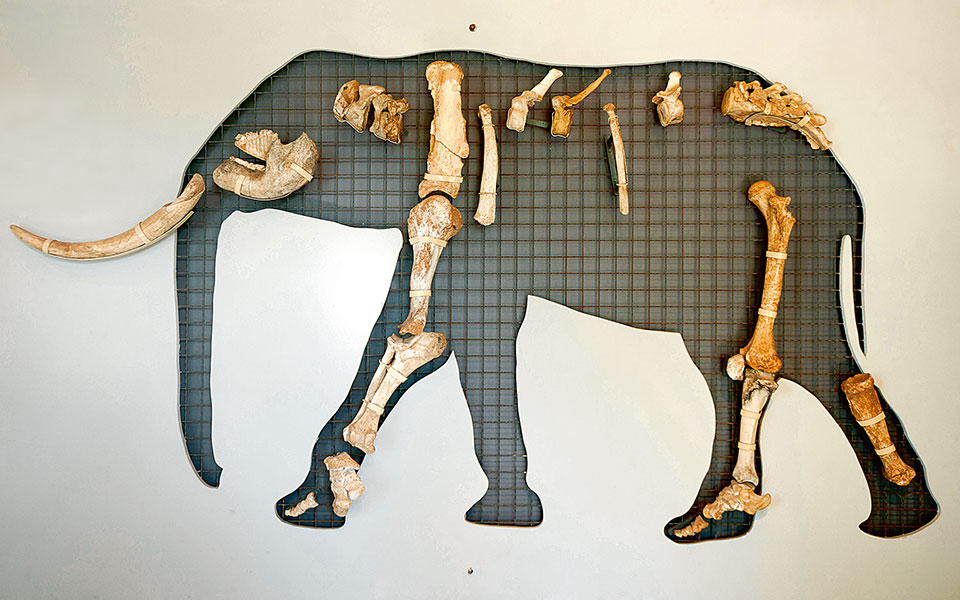

The earliest inhabitants of the Dodecanese were not people, but fauna – the birds, deer and other animals of mainland Asia Minor that flew, swam, crossed then-existing land bridges, or floated on fortuitous “rafts” of driftwood to reach the near-shore islands. Among them, beginning some 45,000 years ago, were Middle/Late Pleistocene dwarf elephants – essentially small-to-medium-sized versions of the animals we know today, which, surprisingly, were very good swimmers (naturally equipped with their own proto-snorkels!). Their fossilized teeth and bones (dating before ca. 4000 BC) were first found in Harkadio Cave on Tilos in the early 1970s, but since then also in Rhodes, Kasos, Kalymnos and beyond, in Crete, Naxos and Delos. This Pleistocene faunal migration set a pattern that Neolithic humans, and later sea travelers, would subsequently also follow, using the Dodecanese islands as stepping-stones to increasingly explore and inhabit the Aegean.

© Ministry of Culture and Sports/Ephorate of Dodecanese

© Ministry of Culture and Sports/Ephorate of Dodecanese

ARCHAEOLOGICAL FRONTIER

Many archaeological excavations and surveys have been carried out in recent decades, by Greece’s Ephorate of Antiquities of the Dodecanese as well as non-governmental Greek and foreign missions. Nevertheless, archaeology in the Dodecanese Islands is still a work in progress. Rhodes and Kos have received the greatest attention; but the “future of the past” is bright, as more and more work is also being done in smaller places such as Kalymnos, Astypalea and Gyali. Informative local museums now exist in many places – including Astypalea, Kalymnos, Karpathos, Leros, Nisyros and Symi. A number of them are recent constructions, while others have been freshly renewed with striking exhibits – for instance, the Kalymnos museum, with its impressive, over-life-size Hellenistic bronze statue, the “Lady of Kalymnos,” recovered from the sea in 1994.

Each Dodecanese island, large and small, has its own individual character and story. Generally, however, the archipelago’s members have experienced similar historical rhythms; with waves of powerful outsiders – from Minoans, Persians, Athenians and Alexander the Great or his successors, to the Romans, Byzantines, Crusaders, Venetians, Turks and ultimately Germans, Italians, British and Greeks – all marching over them and leaving their respective traces. It is this diverse yet familiar blend of nature, history and hardy, charming subsistence that makes these islands worth exploring.

ON EVERY HILL…

By ca. 7000 BC, Neolithic settlers from Anatolia, already competent in sea travel, had crossed the Aegean to reach Crete. In Rhodes, the Erimokastro and Kalythies caves were inhabited in the late 6th and 5th millennia BC (5300-4000/3700 BC). Overall, however, the Dodecanese – endowed with fewer natural advantages than Crete – remained only sparsely populated until the 4th millennium BC, when new settlers (again probably Anatolians) began flooding in. All the major islands and some of the smaller ones (e.g. Halki, Alimia, Gyali) became increasingly inhabited. Nearly every ridge overlooking the islands’ natural ports, according to archaeologist Andreas Vlachopoulos, and every defensible hill rising above arable countryside was occupied by Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age fishermen, farmers and herdsmen. On many sites, obsidian for chipped-stone tools, originating from either Milos or Gyali, points to the importance of seaborne trade. On Gyali itself, archaeologists have discovered Neolithic crucibles for smelting copper, an imported material for which the island’s residents likely exchanged their obsidian.

© Clairy Moustafellou

TOWNS AND TRADE

Proto-urban settlements first appeared in the Dodecanese in the Early Bronze Age (EBA), such as Asomatos (2500 BC-2050/1900 BC) in northwestern Rhodes. Neighboring EBA Cycladic culture extended southward at least as far as Astypalea, where finds include a typical white-marble, violin-shaped figurine and spiral rock-art representations. With their high level of shipbuilding technology, the island people of the East Aegean, observes archaeologist Aleydis Van de Moortel, were innovative, accomplished sea travelers – the first in the Aegean to use the sail. Through subsequent Middle Bronze years (2000-1600 BC), although Minoan Crete exerted an expanding influence in the Aegean, the robust native culture of the Dodecanese remained predominant, archaeologist Toula Marketou notes, as seen at Trianda/Ialysos, in Rhodes, and Serayia (or “Serraglio”) beneath present-day Kos Town.

As Minoan and eventually Mycenaean exchange increased in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (ending ca. 1100 BC), evidence for these western traders shows up in numerous Dodecanese islands, including Karpathos, Kasos and Symi. Just as the archipelago’s earliest, Eastern settlers had used the Dodecanese to move westward, so the Cretans and mainland Greeks now island-hopped eastward as they sought to open up new commercial contacts with southwestern Anatolia and beyond. Marketou and others have pointed to the striking similarity between the natural and manmade features of the “Departure Town” in the Fleet Fresco at Akrotiri (Santorini) and the real-life landscape, wild fauna and architectural remains of Ialysos in Rhodes. Behind Ialysos, a Mycenaean citadel has been detected on Mt Filerimos, as well as at Pigadia/ancient Potidaion (Karpathos) and Poli (Kasos).

© N.E. Toli Collection

MARITIME POWERS IN PEACE AND WAR

The years surrounding Santorini’s catastrophic eruption (ca. 1625 BC) mark a transitional era, when Dodecanese ways finally “hybridized” with those of outsiders. Mycenaean imports increased, settlements were established (or revitalized), local workshops producing Mycenaean pottery appeared and chamber tombs were introduced. Rhodes’ leading towns, Ialysos, Kameiros and Lindos, later became the settings for the great Dorian-founded cities of the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic eras. Homer’s retrospective verses (Iliad 2.653, 2.676) refer to the southern Dodecanese as the Calydnian islands and record that Rhodes had sent nine ships to the Trojan War (1218 BC); Symi three ships; and Nisyros, Karpathos, Kasos, Kos and others collectively thirty ships.

© Shutterstock

© From the book “Rhodes-one-jundrend years of photography 1850-1950”, Simeon Dontas

FRIENDS, FOES AND FICKLE FORTUNE

Through their history, the Dodecanese people on their scattered, vulnerable islands often had to choose sides, form alliances and suffer lengthy servitude under foreign masters, while on a path to eventual freedom. Kos and Rhodes joined forces in the Archaic period, but were subjugated by the Persians in the early 5th c. BC. Nisyros and Symi, too, were pressed into Persia’s ranks, compelled, like their neighbors, to supply Xerxes with ships. Following the encroaching Easterners’ final defeat at Salamis and Plataiai (480/479 BC), Rhodes’ major cities, Kos and all other Dodecanese centers became tributary Athenian allies within the Delian League.

In Classical times, during the Peloponnesian War (431- 404 BC), and in the contentious early years of the Hellenistic era (late 4th-2nd c. BC), many of the islands found themselves equipped with signal towers, garrison outposts and fortresses, while outlying residents occasionally fortified their farmsteads. Today, the ruins of these installations can be viewed almost anywhere one looks, on Agathonisi (Kastraki), Arki, Patmos (acropolis), Lipsi (acropolis), Leros (Partheni Valley, Xirocampos), Kalymnos (Empolas, etc.), Tilos (Kastellos), Karpathos (Brykous), Ro and notably Nisyros, where Vlachopoulos describes Palaiokastro – with its six towers and over 200m of wall – as “one of the most impressive, best-preserved fortification works of the ancient world.” Castle lovers will also delight in Byzantine, Crusader and later fortresses on Rhodes, Kos, Kalymnos, Leros, Patmos, Nisyros, Alimnia, Chalki and Kastelorizo (“Castello Rosso”).

The Dodecanese reached a peak when Hellenistic Rhodes emerged as a major, far-reaching sea power, whose code of maritime law ruled the Eastern Mediterranean. Commerce and resulting prosperity flourished, until the Romans, eager to exert their own expanding imperial authority, moved into the area, suppressed Rhodes and opened Delos (166 BC) as a competing free port. Affluent Romans built luxurious villas, baths and temples, while Julius Caesar, a prominent investor in the region, once endured an infamous kidnapping by pirates (74 BC), records the biographer Plutarch (Jul. Caes. 1,2), near the Dodecanese island of Pharmakoussa (Farmakonisi). Ultimately ransomed after thirty-eight days, during which he calmly wrote poetry and speeches, Caesar promptly hired a ship, tracked down his former captors and had them crucified.

As the Roman Peace waned in the 3rd c. AD and the Empire was sub-divided, the Dodecanese, initially ruled by Byzantium, entered a long period of alternating turmoil and quietude. After the Crusaders’ capture of Constantinople (1204) and during the Frankokratia (13th-16th c.), the islands intermittently fell under the authority of either Byzantine or Western rulers, particularly the Knights of St. John. They seized Rhodes in 1309, converting it into the seat of a mini-empire that soon encompassed the entire archipelago. Evocative traces of their regional command are widely evident, especially in the castle, Grand Master’s Palace and medieval city of Rhodes. In 1522, however, the Dodecanese succumbed to the Ottoman Turks. Their rule was briefly interrupted by the Venetians (1570) and the Greek independence movement (1820s), but the Dodecanese were left out of the new Greek State that formed after the 1821 Revolution and remained under Turkish control until Italy took over the group in 1912 – without Kastelorizo.

© Visualhellas.gr

RECLAMATION, RAVAGES AND REVIVAL

With the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War (1911) and the Dodecanese’s subsequent takeover, the islands once again suffered invasion by forces from the Italian peninsula. Although initially welcomed as liberators from the Turks, and ruling relatively benignly until the 1930s, these latest Italians, with the rise of fascism, eventually ratcheted up their authority – heavy-handedly imposing Italian culture on the Greek islanders; redirecting children’s education away from Greece towards Italy; levying taxation without political rights; attempting to cut ties between the Greek Orthodox Church and Constantinople; and banning or regulating Orthodox-related activities including festivals, pilgrimages, weddings and funerals. The Dodecanese economy stumbled, as shipping, trade and local industries were also restricted. Leros’ deep natural port at Lakki (“Portolago”) became a major Italian naval base. On the positive side, Italian archaeologists conducted numerous excavations, restored important monuments and greatly expanded their era’s knowledge of the islands’ rich past.

Perhaps no individual island’s history is more iconic of the Dodecanese’s tumultuous struggle and foreign exploitation in the first half of the 20th century than that of Kastelorizo. World Wars I and II encouraged successive occupations of Kastelorizo by the French (1915-21), Italians (1921-43) and British (1943-47). The Dodecanese generally were used by the Allies as a staging area in both conflicts, which led to repeated enemy bombardments. German bombing of Kastelorizo (1917-18) and Leros (1943) were particularly destructive and deadly. Not until 1947 were the Dodecanese islands finally incorporated into the modern state of Greece.

Today, with war’s harrowing echoes swept away, the tranquil Dodecanese offer untold opportunities for history-seeking adventurers.