The picturesque islands of the Northern Sporades in the northwest Aegean are renowned for their secluded beaches, crystal-clear seas, and lush green forests. They are also home to hundreds of endangered species of plants and animals, both terrestrial and marine, including the reclusive Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus), and colonies of precious red coral (Coralium rubrum), heavily exploited to make jewelry, and much-prized in antiquity for its healing properties.

Archaeological investigations in the area in recent decades have also revealed an astonishing array of historic underwater finds, including the sunken remains of a 5th century BC shipwreck off the islet of Peristera, immediately east of Alonissos island.

Dubbed the “Parthenon of Shipwrecks” due to its enormous size and well-preserved cargo of amphoras, the 2,500-year-old wreck has become the focal point for Greece’s first underwater archaeological museum, which, after years of planning and collaboration between the National Center for Marine Research, the Ministry of Culture and Sports, the Municipality of Alonissos, and private sponsors, was first opened to the public in August 2020.

© NOUS

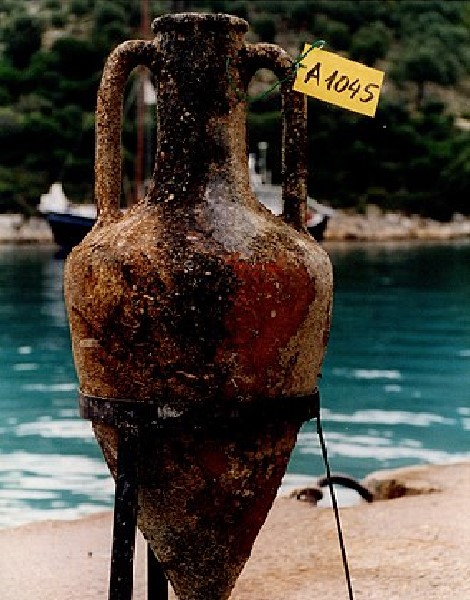

The Peristera wreck, with its cargo of some 4,000 wine amphoras (two-handled ceramic storage jars), is the largest known cargo ship of the Classical period yet discovered. Lying on the seabed at a depth of between 19 and 28m, the site features 22 exhibit areas arranged in a circular pattern, including ballast stones, anchors, ceramics, and other artifacts.

The site is accessible to Advanced Open Water-certified divers or equivalent (qualified to dive to 30m), and is equipped with underwater signposts that provide information on the exhibits and their historical context. Visitors to the underwater museum must book guided tours with an accredited dive center (see below).

© Intime News

Greece’s First Underwater Museum

Until recently, Greece’s rich underwater cultural heritage was strictly off-limits to all but a handful of highly specialized maritime archaeologists. This policy was initially designed by the country’s Ministry of Culture to protect the potentially thousands of submerged sites from would-be looters. With the vast potential for dive tourism, restrictions were steadily relaxed in 2005, opening a select number of sites to the scuba-diving public. A list of the currently accessible wrecks can be found here.

The Sporades islands have long been a popular draw for visitors from elsewhere in Greece and from around the world, threatening not only the fragile ecosystem but also the rich archaeological heritage. To that end, the National Marine Park of Alonnisos and Northern Sporades was established by Presidential Decree in 1992, the first marine park in Greece, covering an area of 2,260 square kilometers; currently the largest marine protected area in Europe. The least populated of the four main islands (the other three being Skiathos, Skopelos and Skyros), Alonissos has become a world renowned ecotourism destination. In 2015, it was the first island in Greece to ban plastic bags.

Located in the heart of the National Marine Park, Greece’s first underwater museum is an important step towards the conservation and management of the country’s maritime cultural heritage, with the aim of serving as a model for sustainable cultural tourism in the post pandemic era. Accessible by boat from Alonnisos, the museum offers visitors with the necessary dive qualifications firsthand experience of underwater antiquities, and a chance to explore the vibrant marine life that inhabits the area.

© Ministry of Culture / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

All tour operators, including dive centers, have a stake in preserving the islands’ unspoiled beauty. Since its inception, the Marine Park’s management and research staff have undertaken the systematic monitoring and preservation of vulnerable wildlife, as well as the protection of underwater cultural heritage. To that end, the museum has recently deployed a state-of-the-art, 24/7 surveillance system to guard the Peristera shipwreck from looters, partly funded and supported by US tech giant Microsoft. Using a network of five underwater cameras streaming real-time video data, the uNdersea visiOn sUrveillance System (“NOUS” for short) uses a combination of image processing and artificial intelligence (AI) to determine whether the wreck site is being disturbed.

The brainchild of George Papalambrou, a professor at the School of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering at the National and Technical University of Athens, NOUS, which means “mind” or “intelligence” in Greek, operates at the Peristera wreck site at depths of 23 to 33m over an area of 300 square meters. The wreck is providing a pilot study for the system, and it is hoped that similar surveillance systems will be applied to other at-risk underwater archaeological sites in Greek territorial waters in the future.

© Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / Public domain

The Parthenon of Shipwrecks

The Classical-era wreck was first reported to the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in 1985 by local fisherman Dimitris Mavrikis, who noticed a large number of amphoras on the seabed off the west coast of the islet of Peristera.

Subsequent archaeological survey and excavation from 1992 to 2000, led by Greek maritime archaeologist Elpida Hadjidaki, revealed an extensive cargo of 4,200 wine amphoras, with a combined weight of at least 126 metric tons. A host of other artifacts were also discovered amid the tightly packed storage jars, including black-glazed bowls, drinking cups and plates, a small wine jar, oil lamps, a cooking pot and elegant bronze tableware. Analysis of the amphoras and accompanying artifacts indicate the ship sank sometime in the last quarter of the 5th century BC.

Much of the wreck site remains in situ on the seabed, its cargo of amphoras forming a large mound, some 25m by 12m, indicating the original shape of the hull. During the archaeological excavations, small fragments of the wooden hull were discovered, buried in the deepest layers of the site under the mass of amphoras and other artifacts – highly unusual for a wreck of this age, as wood almost always perishes. In total, the archaeologists recovered 82 pieces of preserved wooden planks, including 14 treenails (wooden pegs or pins), within which were found large copper nails, providing important clues as to the construction of the ship.

© Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / Public domain

It is estimated that the length of the wooden hull would have been around 25 to 30m, making it considerably larger than any known wrecks from the Classical period (5th through 4th centuries BC) in the eastern Mediterranean. By comparison, other Classical-era wrecks in the region, including the Kyrenia wreck, discovered off the northern coast of Cyprus, and the Ma’agan Michael wreck from Carmel coast of northern Israel, are only around 11-14m in length. Until the discovery of the Peristera wreck, scholars maintained that much larger vessels, capable of transporting cargoes of up to 150 tons, did not appear in the Mediterranean until much later in the Roman period, from the 1st century BC.

Another fascinating aspect of this wreck is the personal effects of the crew. The finely glazed stemless cups and elaborate tableware are reminiscent of the kind of high-quality items seen at lavish banquets or symposia (all-male drinking parties), suggesting the captain and perhaps senior members of the crew were quite well off. Analysis of the clay used in the manufacture of the drinking cups indicates they originated in Macedonia.

© Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / Public domain

© Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities / Public domain

Amphoras, the “jerrycans” of antiquity

Amphoras are often described as the “jerrycans” of antiquity. They were both durable and easily portable, holding up to 30 liters of wine, olive oil, honey, or other organic products. To the trained eye, the shape of the jars and any visible markings – handle stamps, for example – can help to identify their place of manufacture. As such, amphoras recovered from wreck sites have been invaluable in building up a comprehensive picture of the seaborne trade routes that crisscrossed the ancient Mediterranean.

Many of the amphoras on the Peristera wreck were found intact, although the clay stoppers protecting their liquid contents have long perished. At least half were manufactured in the Macedonian port of Mende (Chalkidiki), a region famed for its viticulture in antiquity, while many others came from ancient Peparethos (Skopelos). The orientation of the amphora mound points to the southeast, offering clues as to the ship’s intended direction of travel during its final voyage. Peparethos was most likely the last port of call before disaster struck.

The ship sank in the time of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC), when the city-states of Athens and Sparta vied for supremacy of the ancient Greek world. Scholars have speculated that the ship belonged to a wealthy Athenian merchant, and may have run into stormy weather while sailing near the coast. Some fragments of the wooden hull appear blackened and charred, suggesting that a fire had broken out onboard at some point, but the circumstances of the ship’s sinking remain unclear. Was it an act of piracy? Or was it simply overloaded with cargo?

© Shutterstock

Useful information

Following its successful pilot season in 2020, which ran from August to October, the Alonissos Underwater Museum reopened to the public on June 1st, 2021, for the duration of the summer dive season. Bureaucratic issues quickly ensued, however, with the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities citing a lack of available personnel to safely monitor the site from the surface.

Nevertheless, at present, recreational divers who want to explore the Peristera wreck this summer must do so under the strict supervision of experienced and accredited dive instructors, specially trained by members of the Ephorate.

There are currently three dive centers on Alonissos that organize guided visits to the site:

Alonissos Seacolours Dive Center

Ikion Diving Center, Alonissos

Divers must book their Peristera dive at least one week in advance, as a list of the participants must be sent to the Underwater Museum’s operating body. There are four time slots to visit the site per day. The maximum number of divers for each slot is eight, split into two groups of four.

More information can be found on the Museum website.

For non-divers, a modern information center has been set up in Alonissos’ main town, Chora, giving visitors the opportunity to virtually explore the ancient shipwreck through the NOUS cameras, installed on the seabed.

As a summer vacation destination, Alonissos enjoys a relaxed, laid-back atmosphere, ideal for those seeking to escape the crowds. Famous for its greenery, the island boasts picturesque villages, hiking trails, traditional tavernas, and many beautiful beaches. For more information on Alonissos and the National Marine Park, click here and here.