In a post by the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA) currently circulating on social media, an ancient bronze helmet has caught the attention of the public.

The well-preserved helmet was first uncovered in 2007 by a Dutch dredging ship in the bustling Mediterranean port of Haifa. The ship’s owner, Mr Hugo van de Graaf, reported the find to the Marine Archaeology Unit of the IAA, where it underwent meticulous cleaning and conservation.

Subsequent analysis of the extraordinary artifact, now on display in Haifa’s National Maritime Museum, revealed it to be a helmet of the so-called “Corinthian type”, named after the ancient Greek city-state that first produced and distributed it around the Mediterranean basin in the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

While news of the discovery is not new, the fact that is has resurfaced on social media has raised questions regarding its historical context. What was a bronze helmet of Greek origin doing so far from home?

© Staatliche Antikensammlungen (Inv. 4330)

© Jona Lendering - Livius.org

Underwater discovery

The helmet is the first of its kind to be found off the coast of Israel, preserved by the soft marine sediments at the bottom of Haifa Bay. Based on its style, archaeologists have dated it to around 600 BC.

One of the most striking aspects of the helmet is its elaborate decoration, including lions and snakes, and the intricate pattern of a peacock tail (or “palmette”) around the eyes. Even more remarkable are traces of gold leaf on its surface. Few soldiers could have afforded such an expensively-made helmet, so the owner must have been a wealthy, high-status individual, perhaps in a command role.

“The gilding and figural ornaments make this one of the most ornate pieces of early Greek armor discovered,” commented Kobi Sharvit, director of the Marine Archaeology Unit.

A similar example was found off the coast of Giglio, a small Italian island in the Tyrrhenian Sea, by a British diver in the early 1960s. The area where it was discovered was later surveyed by a team of underwater archaeologists in the 1980s, who determined it was the site an ancient Greek or Etruscan shipwreck, also dated to around 600 BC.

The helmet in question was intricately inscribed with snakes and wild boars – “a masterpiece of ancient art and technology”, remarked Mensun Bound, leader of the expedition. In a cruel twist of fate, following its recording and conservation, the helmet disappeared and its whereabouts remain uncertain.

An Iconic Helmet

The Corinthian helmet was the most widely used and iconic design in the ancient Greek world. Frequently depicted in vase paintings, often with characteristic horsehair crests, it is notable for the all-round protection is gave the wearer. It was expertly made from a single sheet of bronze by means of repeated heating and hammering, with almond-shaped holes for the eyes and a narrow slit for the mouth.

Corinthian helmets were an essential part of the hoplite panoply, the archetypal heavy-infantry solider that dominated the battlefields of Archaic and Classical Greece. Other weapons included a large circular shield called an aspis or hoplon, a long spear for thrusting and throwing, reinforced linen or bronze body armor (cuirass), bronze greaves (shin guards), and a sword.

The hoplite’s armor would have been prohibitively expensive for many in ancient Greek society. As such, only men from the wealthier middle classes would have served their city-states in the rank and file of the heavy infantry.

© National Etruscan Museum, Villa Giulia, Rome (inv. No.22679)

Soldiers for hire

Lying submerged for over two and half thousand years on the seabed, one theory is that the helmet may have belonged to a wealthy Greek mercenary in the service of a foreign army on campaign in the coastal southern Levant (modern-day Israel) towards the end of the seventh century BC.

It is widely known that many Greeks fought in the service of foreign empires at this time, notably the Egyptians. Their experience in overseas campaigns and their development of effective military tactics, including the massed phalanx formation, made them highly sort after as mercenaries.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Oblomov2

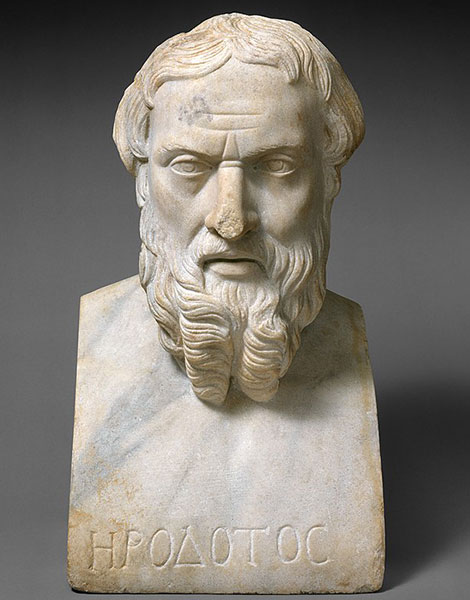

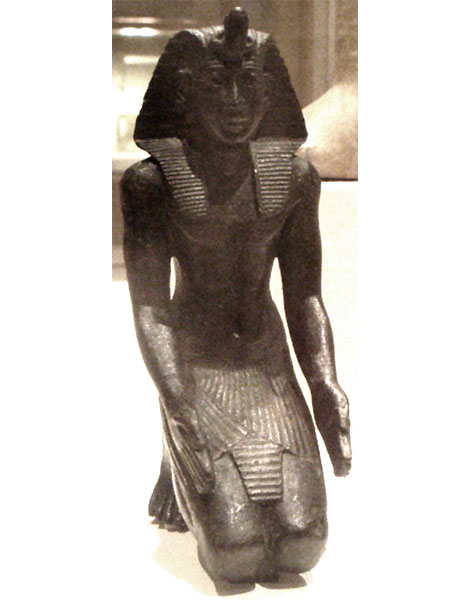

In Book 2 of his Histories, Herodotus recounts how the Egyptian Pharaoh Psamtik I (664–610 BC) invited Greeks to colonize parts of the Nile Delta. In return, they joined his military expeditions against the Assyrian Empire towards the end of his reign.

Herodotus refers to mercenary troops from the Greek colonies of Caria and Ionia (Anatolia) who fought in these expeditions as “bronze men from the sea”.

© Metropolitan Museum of Art

© Patrick Gray - https://www.flickr.com/photos/136041510@N05/22472068136/

Military campaigns in the Levant

Egyptian intervention in the Levant continued under Psamtik’s successor, Necho II (610–595 BC), who sought to counter the westward advance of the emerging super-power of the time, the Neo-Babylonians. He launched a successful military campaign in support of the now ailing Assyrian Empire, Egypt’s former nemesis, becoming the first pharaoh to cross the river Euphrates since Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC), nearly a thousand years before.

Necho’s first campaign culminated in the Battle of Megiddo (609 BC), mentioned in the Bible (2 Kings) and the Jewish Talmud. The battlefield of Megiddo is on a large elevated plateau close to the coastal plain in northern Israel, big enough to accommodate thousands of troops. Incoming mercenaries from Greek colonies in the eastern Mediterranean in support of the Egyptians and their Assyrian allies would have landed nearby, along the Carmel coast.

© Keith Schengili-Roberts

© Daniel Baranek

The late 6th – early 5th century Greek geographer, Scylax, recorded a coastal city in that area, which may be a reference to Tel Shikmona (ancient Sycamine), near the modern-day city of Haifa. It is here that ships carrying troops and supplies may have landed, and it is in this area offshore that the ornate bronze helmet was found in 2007.

The Egyptian pharaoh launched a second campaign against the combined forces of the Babylonians, Persians, Medes, and Scythians a year later, reasserting his power further north in Syria. At the Battle of Carchemish (c. 605 BC) against Nebuchadnezzer II, the longest-reigning, most powerful ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the Egyptian forces and their allies were finally routed. The battle, again mentioned in the Old Testament Bible (Ezekiel 30), signaled the end of the Assyrian Empire as an independent power and brought a halt to Egyptian intervention in the Near East.

© Patrick Gray - https://www.flickr.com/photos/136041510@N05/22497968145/

Ancient Greek Marines

The owner of the helmet that ended up on the seabed off Haifa may well have been a Greek mercenary in the service of the Egyptian pharaoh in either one of these campaigns. The helmet itself could have been lost in a naval engagement off the coast, either in a sinking ship or the mercenary himself falling overboard. Alternatively, the helmet could have simply been accidentally dropped over the side.

Naval operations likely took place along the southern Levantine coast during these campaigns in support of the land troops. Herodotus mentions that Necho II built oared warships in the Nile Delta for service in the Mediterranean. As such, squadrons of ships manned by Greek crews would have sailed in support of the Egyptians and their Assyrian allies.

Oared warships in the late seventh century carried around 10 to 20 “marines” (epibatai) on the upper deck, heavy infantrymen (hoplites) adapted to naval warfare. When ships came alongside each other in battle, the marines would attempt to board and spear the enemy, or cut them down with their swords.

© Shutterstock (Elenarts)

It is interesting to note that the unit insignia of the 32nd Marines Brigade – the modern-day Greek marines – depicts the Argo (Ἀργώ), the famous ship of Jason and the Argonauts. Ancient authors imagined the Argo as an early type of warship, the first to go on a long-distance sea voyage.

The Marine Archaeology Unit of the IAA is keen to initiate a survey in the area of its discovery in search of other archaeological materials, perhaps even the remains of a sunken Greek warship.