Canadian sailor Lawrence Lemieux was racing at full speed towards an Olympic medal in the Finn class, off the coast of Busan, South Korea, in September 1988. Although he was in second place near the halfway point of his race, he never placed. Spotting two athletes from Singapore whose boat had capsized, Lemieux changed course and pulled them out of the water; one of them, in fact, had been injured. He waited with them until a rescue boat arrived and only then did he rejoin the race, finishing in 11th place.

By responding the way he did, Lemieux demonstrated that he fully embodies the Olympic ideal, as summed up by the International Olympic Academy (IOA), which aims to study, enrich and promote Olympism: “Olympism is a way of life based on respect for human dignity and fundamental universal ethical principles, on the joy of effort and participation, on the educational role of good example, a way of life based on mutual understanding.”

Lemieux’s is not the only example. Recall the North and South Korean athletes at the opening ceremony of the Sydney Olympics, who marched under a common flag, briefly setting aside the differences that had separated their countries for decades. Recall the romantic story of Olga Fikotova, a discuss thrower from Czechoslovakia who, at the Melbourne 1956 Games, met, fell in love with and eventually married US hammer thrower Hal Connolly – a happy side story in the prevailing Cold War climate. Recall Ethiopian Abebe Bikila, the barefoot marathon runner who competed in the Rome Olympics, embodying the “joy of effort” and winning the gold medal despite numerous adversities.

“Olympism is a way of life based on respect for human dignity and fundamental universal ethical principles, on the joy of effort and participation, on the educational role of good example, a way of life based on mutual understanding.”

© Getty Images/ Ideal Image

© Bridgeman Images

© Getty Images/ Ideal Image

“The joy of participation is obvious every four years during the opening ceremony, in which thousands of athletes, some famous and others not, walk beside one another with their eyes reflecting one thing they share: the awe of the supreme honor of continuing an ancient tradition as ambassadors of the highest ideals.”

The value of participation

As Pierre de Coubertin, the man who revived the modern Olympics, said: “The most important thing is not winning, but taking part.” Marathon runner Abdul Baser Wasiqi could have given up when he suffered a serious muscle injury in his leg just before the start of the race in 1996 in Atlanta. Instead, the Afghan runner limped for 42 kilometers and finished last after 4 hours 24 minutes, about an hour and a half after his fellow athletes had completed the race. He knew there was no chance of winning and he risked a possible relapse of his injury. But he will always be able to say that he took part in the Olympics; that he ran and finished.

A similar story is that of Britain’s Derek Redmond, a talented but unlucky sprinter who had won gold in many world championships, but whose injuries prevented him from adding an Olympic medal to his collection. In 1992 in Barcelona, he suffered a torn right hamstring about halfway through the 400m semifinal. Writhing in agony and unable to believe his misfortune, Redmond found the strength to continue the race at a limp, though his opponents had already finished. A few seconds later, a man emerged from the crowd and ran to this side, putting his arm around the athlete and helping him to continue. It was his father. Holding each other and with tears in their eyes, the two men finished the race together while thousands of spectators hailed them with a standing ovation.

The joy of participation is obvious every four years during the opening ceremony, in which thousands of athletes, some famous and others not, walk beside one another with their eyes reflecting one thing they share: the awe of the supreme honor of continuing an ancient tradition as ambassadors of the highest ideals. The Olympic goal, quoting again from the IOA, “is to contribute to building a peaceful and better world by educating youth through sport practiced without discrimination of any kind, and in the Olympic spirit which requires mutual understanding with a spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play.”

Recall African Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos, in Mexico in 1968, who made a plea for a world free of discrimination with their bowed heads and raised fists, as the US national anthem was being played at the medal ceremony for the 200m race. Remember the legendary Jesse Owens, who, without necessarily trying to, challenged Hitler and his theory of Aryan supremacy by winning four gold medals before the Nazi dictator’s eyes in Berlin in 1936 (100m, 200m, 4 x 100m relay and the long jump). Recall the Croatian sailors in Beijing who, having been eliminated, lent their boat to their Danish fellow athletes when theirs was damaged just before the start of the final. The Danes subsequently went on to win gold.

© Getty Images/ Ideal Image

© Getty Images/ Ideal Image

© Getty Images/ Ideal Image

The value of symbols

The spirit of the original Games at Olympia is also transmitted to the present through the symbols of the modern-day events. Recall the sacred truce that allowed athletes from near and far to travel and take part in the Games without trouble along the way. At the same time, allies and enemies competed in honor of the unity of the people and of human beings, just as many centuries later, the same unity was reflected through the five intertwined circles on the Olympic flag. All of the symbols have their own meaning.

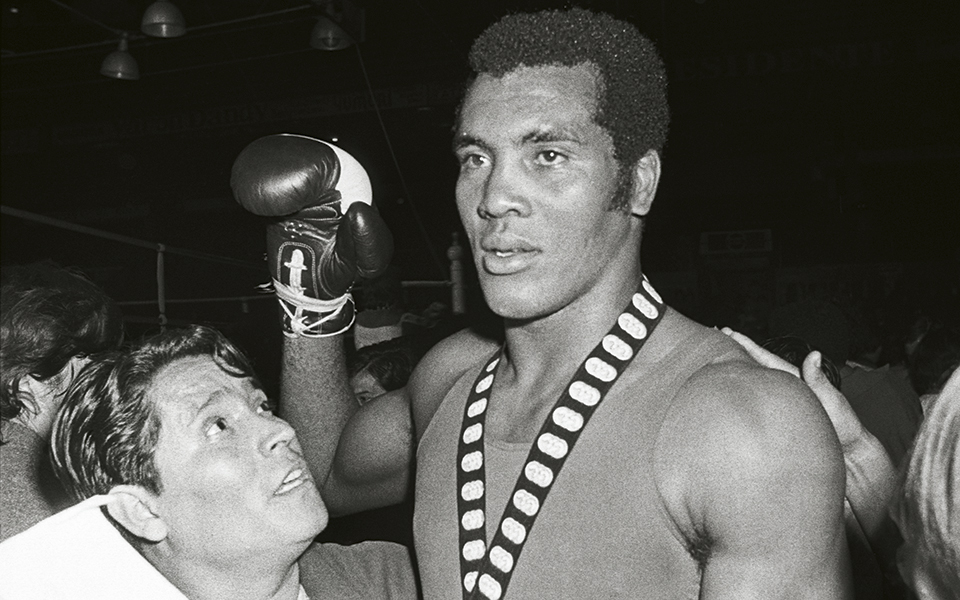

Recall the kotinos, the olive wreath used to crown the ancient Olympic champions. The reward is purely moral and cannot be measured. Cuban boxers Teofilo Stevenson and Felix Savon proved it when they refused – the former in the 1970s and the latter 20 years later – multimillion-dollar offers to turn professional and fight in the American rings against the boxing stars of their time. They chose instead to compete for their country and for the ideals of the Olympic Games. Along with a Hungarian, the two Cubans are the only boxers to have won three Olympic gold medals in the sport – Stevenson in 1972, 1976 and 1980, and Savon in 1992, 1996 and 2000. “O Ancient immortal Spirit, pure father of beauty, of greatness and of truth,” wrote Greek poet Kostis Palamas in the Olympic Hymn.

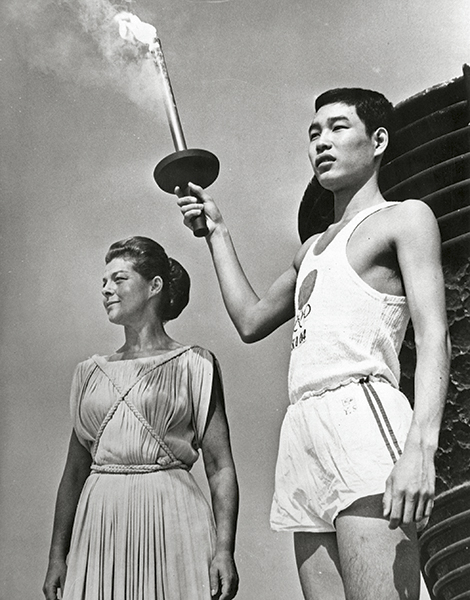

And, of course, there is the Olympic flame. Have you ever wondered why it burns throughout the Games, just as it did at the Olympian Prytaneion in ancient Greece? According to the myth, Prometheus gave fire to humans to teach them about civilization. The Games remind us of that gift; they remind us that civilization is our responsibility and our duty. Recall what happened in Tokyo in 1964, when the last torchbearer entered the stadium to signal the start of the Games. He was a young amateur runner named Yoshinori Sakai, who had been born in Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the day the atomic bomb fell on his city. Sakai carried more than just the Olympic flame that day. He carried the message of the high priestess’ call during the flame lighting ceremony: “And you, Zeus, give peace to all peoples on Earth.” He carried the message of life.

“Recall the kotinos, the olive wreath used to crown the ancient Olympic champions. The reward is purely moral and cannot be measured.”