Τhe power of those journalists who are political cartoonists lies in the establishment of a specific code of communication with part of the public. It takes time and hard work to develop that code and to give it stability, but once it’s in place the results are easily comprehensible and reception is traightforward and therefore powerful. The success of that reception, however, rests on a few fundamental presuppositions.

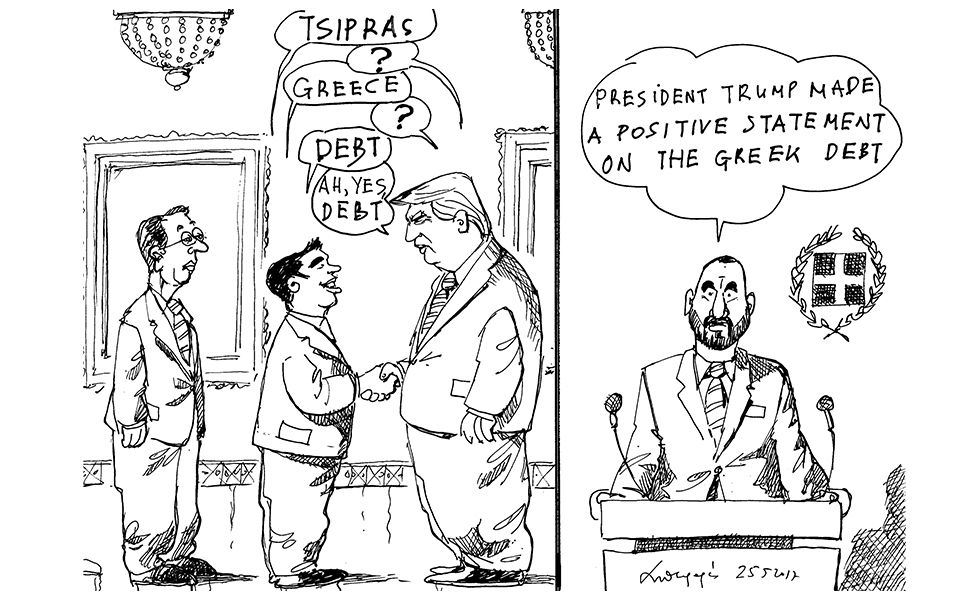

The language in which we cartoonists converse with our public is enigmatic, laconic, full of allusions and, we hope, witty. Our communication with the reader is instantaneous, the fruit of an everyday moment, and yet there is always the danger that it will be overlooked; that the message won’t get through. Only a particular sort of reader will luxuriate over a daily cartoon, examine it in detail and invest time in solving the riddle the cartoonist is posing (particularly if it’s trickier than usual).

Most people love cartoons for their immediacy; they want a cartoon to be easy to understand. They enjoy being surprised by it in a passive sort of way – and if all these conditions aren’t fulfilled, they abandon it. If their expectations are met, however, the cartoon can become unstoppable, a way for the public to express itself, a common trope. Then it becomes a language with unspeakable power.

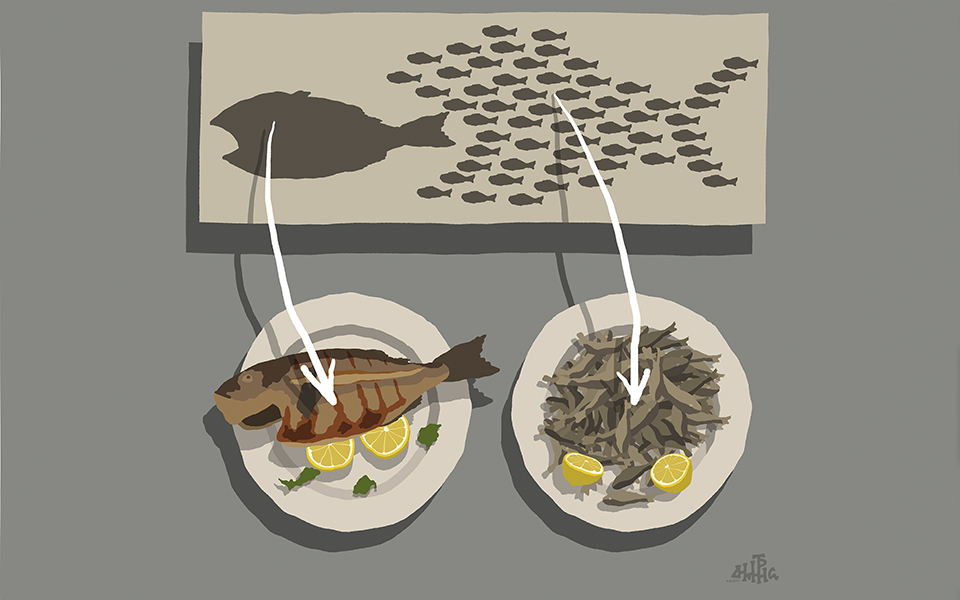

A cartoonist gives the news back to the reader as a funny image, a subversive point of view, a satiric commentary. He does this in a way that must be clear and uncomplicated, as easily intelligible as possible, but not in an explanatory fashion. It’s like when someone tells you a joke: if they have to explain it to you, the joke doesn’t work. The cartoonist should never write more than the drawing requires; he counts his words like a poet, because otherwise he runs the risk of the cartoon going soft. Comprehension is key in our work – not explanation.

Let’s pause for a moment on the term “reader.” It’s a trap for a journalist to imagine or invent a particular sort of reader, one who agrees with his own views, and to try to cultivate a consistent, steady relationship with him, in the belief that both parties will be mutually satisfied by that identification. This sort of imagined reader will lead him astray.

As we all know, a reader isn’t a collective subject; therefore, it’s impossible for him to desire any particular thing. For each person who agrees with your opinion, there is another who disagrees. Meanwhile, society is more divided than ever before, with no-go areas, fanaticisms and unlikely alliances. So which reader are we talking about? The Everyman who reads the newspaper; which is to say, a public that presumably shares similar political views and perhaps also cultural references?

But every journalist’s ambition, particularly in the internet age, is to have the widest possible audience and not to be defined by the profile of the presumed average reader of the medium in which he works. This is even more the case for a cartoonist who strongly believes that a sense of humor has no limits – that, if you find the key, your work will spread and be welcomed, even by parts of the population that don’t agree with your political views.

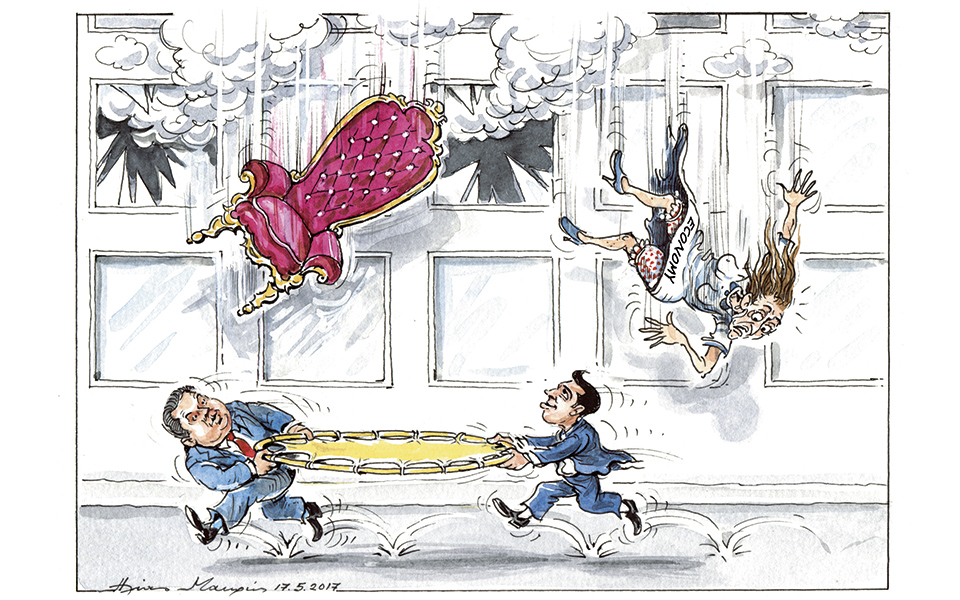

A cartoon reflects the talent of the cartoonist, his sensitivities, his education, his aesthetics, his hard work and his instincts. The reader chooses to follow the cartoonist or cartoonists who suit him. The relationship that is forged between them over time is usually a tacit one, testified to by sharing on social media or over email, or mentions during phone calls.

On those rare occasions when we happen to meet our readers face-to-face, we realize that each of us has a readership that isn’t limited by party positions, a readership in which our efforts find a response, as does our sense of humor, our perspective, our knowledge and the aesthetics that are implicit in our cartoons. A cartoonist is closely tied to this readership, not as regards their respective political views, which can change and shouldn’t in any case be allowed to ensnare us, but as concerns a certain cultural plane and a shared taste. This is the segment of society over which the cartoonist has influence, and it is in this audience that he finds himself reflected.

A political cartoonist should never allow himself to be paternalistic or didactic. It is against the nature of his work to try to give lessons to society – he wants to make people laugh. But that laughter always springs from a sense of some political lack, contradiction, mistake, inconsistency or subversion. Therefore, the only way for him to operate is to make his own political and personal views his starting point.

If, instead, he makes it his goal to flatter what we call common sentiment, his work will be cheapened over time and will eventually betray him. Common sentiment is, in my opinion, often just what shouts the loudest. If cartoonists allow themselves to begin catering to it, they soon find themselves simply hopping from trend to trend, losing their unique identities and becoming playthings of the merciless stream of current events.

Adherence to one’s own values and beliefs should be a cartoonist’s constant guide, while the antenna of his sensitivity to social injustice should always remain raised. The dangers of populism and simplicity on the one hand and of elitism and self-isolation on the other are always there – we journalists have to keep in mind that we are neither union leaders responsible for representing a particular public nor novelists who are allowed the luxury of departing from reality. The power of our work – autonomous, unprejudiced, and mature – arises from the reasonable balance each of us must discover.

A cartoonist is constantly judged because he is entirely exposed. His readership may not know what he looks like, but the faces in his drawings are familiar and reflect him with precision. No one who addresses himself to the public for years can keep his intentions hidden, or his cultural or educational background, or his talent and its limitations.

For many, political views play a secondary role in how they view a journalist – they pay more attention to the quality, the honesty, the openness and the validity of the weapons he uses to defend his position. Cartoonists, like all journalists who practice the satiric arts, have one great advantage: humor. Humor can become the passport that allows us to enter whatever political and social space hasn’t already been closed off by prejudgment.

If one believes that mature individuals have the ability to make fun of themselves, then they can easily accept the satire of a third party and laugh along with him. This is the greatest strength of the work of the political cartoonist: to break down society’s ideological and political walls, and to send his little inky people everywhere.

Andreas Petroulakis is a prominent Greek political cartoonist. Self-taught, he started his career in 1985 and has been working for the newspaper Kathimerini since 2000.