Disability in Ancient Greece: Myths, Facts, and Accessibility...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

Like the courtyard of an ancient Greek villa, the AMK’s central atrium is a dynamic space alive with light, color, elegant ladies and respected gods, including Artemis, Hermes and Hygeia.

© Dionysis Kouris

For insight into the rich history and impressive artistic legacy of ancient Kos, the first stop for sightseers should be the Kos Archaeological Museum. Originally founded in 1936 by the Italians, the island’s rulers at the time, the museum is among the most recent of Kos’ archaeological monuments and infrastructure to be refreshed, restored and made more “visitor-friendly.” After a series of largely EU-funded improvements to local archaeological sites and facilities stretching back over a decade (including improved signage, re-erection of fallen columns and the opening of new exhibitions at the Casa Romana and the small Epigraphical Museum beside the Asclepieion), the Archaeological Museum of Kos (AMK) has had its turn. Closed for more than four years while undergoing major works, the distinctively styled museum officially reopened its doors in September 2016.

The AMK’s pre-WWII architecture is in itself one of the museum’s most historically evocative exhibits. Its façade, with three tall, attenuated arches, bears a unifying resemblance to other historic buildings in Kos Town (e.g., Aghios Nikolaos Church) and brings to mind that period of great archaeological activity when Italian authorities undertook large-scale excavations in the center of the modern town, which had recently been reduced to complete ruin by the devastating 1933 earthquake. Although a disaster for the people of Kos, that earthquake also represented an opportunity for the island’s ancient heritage to be brought to light. Today, for the first time, as archaeologist Stamatia Marketou of Greece’s 22nd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities points out, artifacts previously out of sight in storerooms, together with information gleaned from the investigations of the Italian excavators into Kos’ numerous sanctuaries, are being presented publicly among the AMK’s newly organized permanent displays.

It cannot be forgotten, however, that Italian authorities in the late 1930s were also responsible for what locals still consider a cultural tragedy for the island, when many exquisite ancient mosaics and statues from Kos were removed and installed as decorations in the Italian governor’s palace in Rhodes – an action reminiscent of ancient Greece and the wealthy Roman collectors who similarly shipped Greek works of art back to Italy to adorn their country villas.

Two Roman women in flowing robes face each other across the museum’s central atrium; Dionysus with a satyr and Pan, left background.

© Dionysis Kouris

A spirited symposium (party) scene, with musicians playing a flute (foreground) and lyre (background) for reclining guests, Roman era.

© Dionysis Kouris

On entering the AMK, the visitor is immediately struck by its charm. Just beyond the foyer, a small atrium (illuminated from above with natural light) is the setting for a magnificent polychrome mosaic (2nd-3rd c. AD). This pleasant space is lined with elegantly carved statues of mythical figures standing on a low socle framed between decorative pillars. At each side, two Roman-era ladies in flowing drapery stand beside the mosaic, as if they have just entered the atrium through the rectangular arches behind them. In another doorway, the god Hermes, seated on a rock and wearing a petasos (a distinctive cap) and winged sandals, presides over the entire scene, a small ram beside him looking up inquisitively. Here we also find Dionysus (with Pan and a satyr), Artemis, Asclepius, and his daughter Hygeia.

All seven of these statues originate from a long-inhabited city villa (House of the “Rape of Europa,” 3rd c. BC – 3rd c. AD) in Kos Town. The unusually fine condition of the figures’ sculpted details is worth appreciating; one of the Roman ladies (1st – 2nd c. AD) wears two rings, while Hygeia carries an egg in her left hand with which she tempts a large, writhing serpent gripped in her right. The mosaic, brought from another nearby villa (House of Asclepius), depicts the healing god first arriving on the island, greeted by a standing Koan who gestures in welcome. Hippocrates, an anachronistic onlooker seated opposite, may represent a harbinger of the great medical achievements and tradition of healthcare soon to be established on Kos by the pioneering physician and his followers (the Asclepiades).

To the left of the atrium, a long gallery holds more sculptural works; these highlight the women of ancient Kos and the island’s close connections with Egypt. These objects, along with an oversize standing figure of a bearded Asclepiadic physician (“Hippocrates,” ca. 330-300 BC), were recovered from the town’s Roman Odeon. The opposite, eastern wing is devoted to displays concerning the urban and rural sanctuaries of Heracles, Asclepius, Athena, Demeter, Aphrodite, the Nymphs and Pan. Votive human and animal figurines, sculpted goddesses, lamps, small vessels and protomae (molded busts) are all displayed here, as are medical instruments and potion bottles.

“In the mosaic from the House of Asclepius, Hippocrates may represent a harbinger of the medical achievements and tradition soon to be established on Kos by the pioneering physician.”

The AMK’s west gallery showcases Hellenistic sculptures of aristocratic women and Ptolemaic Egyptian leaders.

© Dionysis Kouris

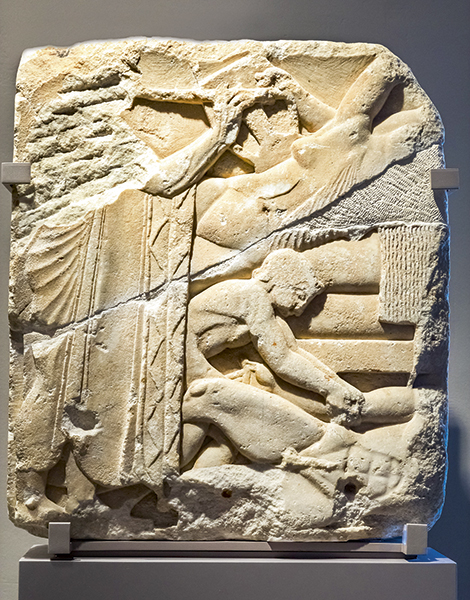

On the museum’s upper floor, thematic exhibits detail the geology of Kos and illustrate the span of Koan history and archaeology, from Neolithic through Roman times (4th millennium BC – 1st c. AD). Minoan, Mycenaean and local artifacts from rescue excavations of the Bronze Age settlement of Serayia near the port of Kos are innovatively presented, some against a backdrop of the archaeologists’ hand-drawn stratigraphic profiles from their excavations. Aspects of the life and death of ancient Koans are reflected in cooking and table wares, children’s toys, boudoir items, loom weights, carved grave steles and a range of grave goods. Transport amphorae and an array of Eastern Mediterranean coins recall the major commercial role and economic prosperity of wine-rich Kos in Hellenistic-Roman times. Other trade goods include a large cache of carbonized figs, while local industry is stunningly represented by balls of brilliant blue pigment discovered in a workshop in Kos’ Agora (marketplace). The vitality of life in ancient Kos is demonstrated by an abundance of evidence for symposia (feasts, drinking parties), including plates, wine pitchers, large two-handled cups and — in one of the museum’s most extraordinary artifacts — a party scene of wild abandon carved on a grave stele that depicts an aulos (flute) player, a nude courtesan lying on a couch with a lyre player behind her, and an ithyphallic male figure on the floor, attended by a young servant boy.

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

A once-mighty city-state overlooking Souda Bay,...

Archaeologists at the site of Aghios...