Athens: A Guide to the City’s Holiday Festivities

From Christmas markets to New Year’s...

Christmas in Greece arrives quietly, yet always with a touch of magic. The festive season begins on December 6, the name day of Saint Nicholas, and lasts until January 6, Epiphany. While most Greeks celebrate Christmas on December 25, some Old Calendarists follow the Julian calendar and mark it on January 7.

Visiting Greece at this time of year is especially rewarding. Towns and villages are calmer but beautifully lit, with festive markets, the scent of roasting chestnuts and rakomelo in the air, and traditions that stretch back centuries. Alongside Christmas trees, you’ll see illuminated boats, hear children singing carols, watch Yule logs burn in fireplaces, and witness pomegranates smashed for good luck on New Year’s Day. Even a short stay offers a glimpse into the heart of Greek Christian life.

In many Greek homes, Christmas starts with the Christoxylo, or “Christ’s firewood,” a large log carefully chosen from an olive or pine tree and brought indoors well before the holiday – a tradition especially popular in the mountains and upland villages of northern Greece. Once lit on Christmas Eve, its flame is meant to warm the newborn Jesus in his manger and, according to folklore, keep the mischievous “kallikantzaroi” – goblins said to roam the earth during the Twelve Days of Christmas – at bay (more on those cheeky tricksters below).

Families often “season” their Christoxylo with almonds, walnuts, and a sprinkle of cinnamon, carefully tending the fire throughout the festive period. The scent of the burning wood fills the house, creating a cozy, rustic atmosphere for family gatherings and quiet winter evenings. For visitors, it’s a small but enchanting ritual that offers a glimpse into the blend of age-old faith and folklore that shapes many Greek Christmas traditions. Sitting by the Christoxylo with a mug hot chocolate in hand is a perfect introduction to the Greek holiday spirit.

A festive nod to Greece’s rich seafaring heritage: twinkling “karavakia” light up town squares and harbors, bringing Christmas cheer to islands and coastal villages.

© Shutterstock

While the Christmas tree has become the most familiar symbol of the season, in Greece you might also spot “karavakia,” or decorated boats, in homes, marinas, and town or village squares. The tradition harks back to Greece’s ancient seafaring past, the god Dionysus and the Athenian winter festival of “Anthesteria,” and to Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of sailors, who inspired families to honor loved ones at sea with miniature – or even full-sized – vessels adorned as festive tributes.

In some coastal towns and on the islands, it’s common to find small caiques – traditional fishing boats – festooned with fairy lights alongside classic Christmas trees, creating a uniquely Greek tableau; a blend maritime tradition, community, and festive cheer. Seeing these illuminated boats, you’re reminded of how deeply the sea is woven into everyday life here – even at Christmastime.

Kourabiedes

© Shutterstock

No Greek Christmas is complete without “melomakarona” and “kourabiedes,” the country’s signature festive cookies. Every year, these mouthwatering treats inspire passionate debates over which reigns supreme (a bit like the Italian “pandoro versus panettone” rivalry): the buttery, almond-studded kourabiedes, blanketed in powdered sugar, or the soft, honey-syruped melomakarona, sprinkled with crushed walnuts. The answer? Both, of course!

Families spend days baking together – “yiayiades” (grandmothers) waxing lyrical as to why their recipe is the best – the kitchen filling with the warm aroma of cinnamon, cloves, and roasting nuts. Unsurprisingly, there are plenty of modern twists, from chocolate-dipped versions to orange-infused syrup, but the old school classics remain unbeatable.

To try making these at home, click here for our recipes.

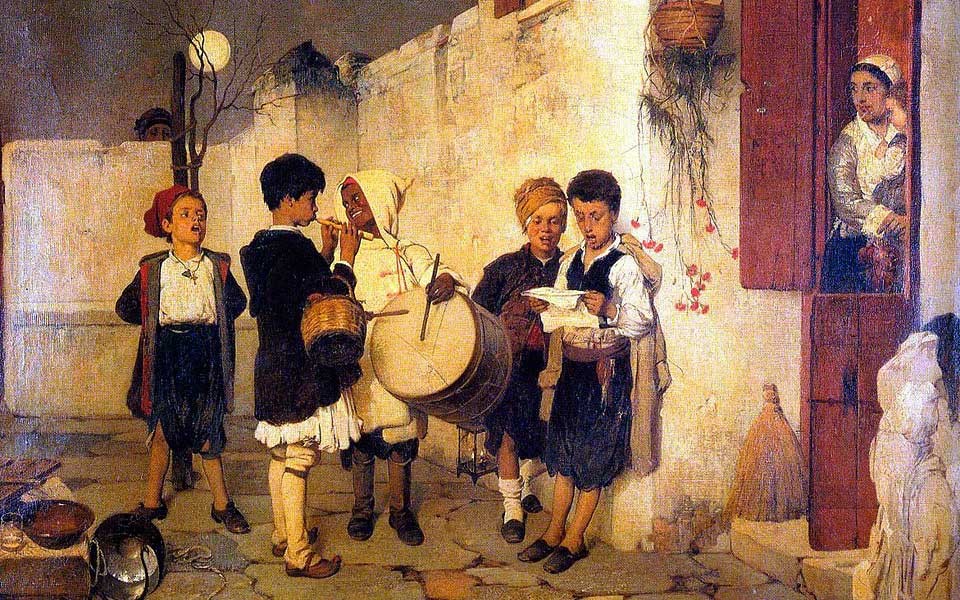

The oil in canvas painting "Carols" (1872) by Nikiforos Lytras, depicting children with different origins singing all together

We often think of carol singing as a distinctly Northern European – particularly British – tradition (think Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol”), but, as usual, Greece has put its own spin on the classic festive ritual. Visitors will likely encounter gaggles of children, roaming the streets with triangles, tambourines, or even sometimes guitars, loudly singing “kalanta Christougenon,” the traditional Greek carols.

On the mornings of Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, and Epiphany, kids will dress up in Santa hats and festive outfits and visit neighbors, friends, and relatives, spreading cheer and wishing everyone health, happiness, and good luck for the year ahead, in exchange for a few euros or sweets, dropped into a hat or collecting tin. The money is then used to buy gifts. The songs themselves are recited in “katharevousa,” an older, more literary form of modern Greek that developed in the 18th century, but the tradition of caroling is believed to have ancient roots.

While caroling may have faded somewhat in the larger urban centers, in villages and small towns it remains a big event. But even in the big cities, you might hear children entering shops or cafés, asking to sing: “Na ta poume?” (“Shall we sing?”), always to the delight of customers.

If you’re in Greece between Christmas and Epiphany, you might hear whispers about the “kallikantzaroi” – tiny goblins that, according to folklore, emerge from below the earth during the Twelve Days of Christmas to cause mischief. They aren’t terrifying monsters so much as playful troublemakers: stories tell of them creeping into houses down chimneys or through cracks in the walls or floorboards, snatching sweets, souring milk, snuffing out fires, overturning chairs, and generally making a nuisance of themselves while everyone is fast asleep.

The lore says these creatures spend most of the year underground, sawing away at the mythical World Tree that supports the earth. When Christmas arrives, they abruptly abandon their task, climb to the surface, and wreak havoc until Epiphany, when a priest’s blessing of holy water – and the start of a new cycle – sends them scurrying back below.

Over generations, Greeks have devised playful ways to keep them at bay: hanging garlic or a colander by the door (they’re said to be compelled to count the holes all night, never going past three, a holy number), keeping the Christoxylo burning, or drawing crosses on doorframes.

The tradition is particularly strong in rural areas, where communities still pass down tales of these cheeky tricksters with a grin – part folklore, part festive reminder to keep a watchful eye on hearth and home.

For more on the kallikantzaroi, click here.

Christopsomo – “Christ’s bread” – is traditionally prepared on Christmas Eve.

© Christina Georgiadou

Every Greek Christmas table is crowned by a “Christopsomo,” or “Christ’s bread,” a large, round loaf of bread, often decorated with dough patterns representing crosses, vines, or more intricate festive motifs. Unlike everyday bread, this loaf is baked with care and reverence on Christmas Eve and reserved for the main Christmas feast. It’s both a culinary centerpiece and a symbol of blessing for the household.

Traditionally, raisins, nuts, and holiday spices are added to the dough, infusing it with a sweet, fragrant warmth, often with a whole walnut (in its shell) placed at the center. Of course, different regions offer their own twists. In Crete, only the finest and most expensive ingredients are used, including rose water, honey, cloves, and sesame, with a white nut tucked into the middle.

In the Ionian Islands, families gather at the home of the eldest member on Christmas Eve. The bread is placed near the hearth, and everyone rests their right hand on the Christopsomo. The senior family member then pours olive oil and wine over it, cuts the bread, shares it among the family, and the feast begins.

If you’d like to try making Christopsomo at home, click here for our recipe.

In Greece, the gift-bringer of the season isn’t Santa Claus as most know him, but Aghios Vasileios, or Saint Basil the Great.

A 4th-century bishop from Caesarea in Cappadocia (in today’s Turkey), he was renowned for his generosity and care for the poor. According to one tradition, he gave away his possession and secretly delivered gold coins to families in need, hiding them in sweetened loaves of bread.

Traditionally, children in Greece – and across much of the Orthodox world – receive their gifts from Aghios Vasileios on New Year’s Day, which marks the saint’s feast. Many households now also exchange presents on Christmas morning, blending in Western traditions associated with Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker, himself of Greek origin from Lycia.

Walk through festive markets or busy town streets today and you’ll still spot the familiar, red-suited figure with a bushy white beard. In Greece, though, the story behind him points less to Lapland or the North Pole and more to ancient Cappadocia – and to a tradition rooted in quiet acts of kindness.

The vasilopita, a sweet-bread cake, hails the arrival of the New Year.

© Kostis Sohoritis

As the clock edges toward midnight on New Year’s Eve, Greek households turn their attention to the vasilopita, a large, round New Year’s cake baked in honor of our aforementioned friend, Agios Vasileios/Saint Basil. Whether it’s a rich, buttery sponge or a bread-like cake scented with orange and vanilla, one thing matters more than the recipe: hidden inside is a single lucky coin, the “flouri,” echoing the saint’s legendary habit of hiding gold coins in loaves of bread.

The cutting of the vasilopita follows a careful order. The head of the household makes a sign of the cross across the cake with a knife, then cuts the first slices. The first is dedicated to Jesus Christ, the second to the Virgin Mary, the third to Saint Basil, followed by slices for each of the family members, youngest to oldest. When the lucky recipient finds the coin, there’s usually a small cheer – and the promise of good fortune for the year ahead.

For visitors invited into a Greek home at New Year, this simple ritual feels quietly magical. Today, the cutting of the vasilopita isn’t limited to family households; it has spilled over into offices and workplaces across the country, usually in the first weeks of January, offering colleagues a cheerful way to bond and welcome the year ahead with hope.

Once the vasilopita has been cut and the New Year officially arrives, attention now turns to “podariko,” the tradition of “first footing.” The idea is simple but taken seriously: the first person to step into a home in the New Year should bring good luck – and must enter with the right foot first.

In many households, this moment is carefully choreographed. A family member or close friend believed to be lucky – or especially kindhearted – is invited to step outside just before midnight, then re-enter as the clock strikes twelve. In some places, the host steps on iron for strength in the year ahead, while the “first footer” is welcomed with kisses and small treats like nuts or sweets. A similar tradition can be found in Britain, particularly in Scotland, where “first footers” are offered a dram of whisky and a traditional cake.

On islands such as Amorgos, the ritual takes on a more symbolic rhythm, with spoken blessings, the turning away of bad luck – and, finally, the dramatic smashing of a pomegranate on the threshold (more on that below). On Crete, some families hang an onion above their front door, symbolizing renewal and growth.

Often following straight on from the podariko, the New Year in Greece is sealed with a wonderfully dramatic gesture: the smashing of a pomegranate on the doorstep. The fruit has long symbolized prosperity, fertility, good health, and abundance, with roots stretching back to hallowed antiquity.

Its meaning is closely tied to the myth of Persephone, who ate pomegranate seeds in the Underworld after being taken there by Hades – a story that can still be traced today at the ancient site of Eleusis, near Athens, where pomegranates are often left as offerings near the Ploutonion, the mythic entrance to the underworld.

Traditionally, the head of the household carries a pomegranate home from church on New Year’s Day and enters the house with the right foot first. Then, with a decisive throw, the fruit is smashed on the threshold. The more the seeds scatter, the better the luck promised for the year ahead – a joyful, slightly messy ritual that sends hope flying in every direction.

Epiphany - Greek style.

© Shutterstock

New Year’s Day may mark a fresh beginning, but in Greece the festive season doesn’t truly end until January 6, the Epiphany – also known as Theophany or Ta Fota (“The Lights”). The day commemorates the baptism of Christ and the revelation of God’s presence, bringing the Twelve Days of Christmas to a meaningful close.

Once again, children head out to sing the “kalanta,” this time recounting the story of Christ’s baptism. The heart of the celebration, however, unfolds by the water. Across Greece – from rivers and lakes to harbors and even municipal swimming pools – priests perform the Great Blessing of the Waters, casting a cross or Crucifix into the cold water as crowds look on.

Young men then dive in to retrieve it – although an increasing number of girls are joining in – braving icy temperatures for the honor and blessing that come with it. The ritual washes away the old year, banishes lingering bad energy (not to mention those mischievous kallikantzaroi), and sends the new one forward, renewed and full of light.

If you want to learn more about this sacred ritual and other traditions that unfold across Greece in January, click here.

From Christmas markets to New Year’s...

Just an hour from Athens, Kea...

Step off the beaten path this...

Discover festivals, beaches, food, and hidden...