In Search of Odysseus

Archaeologists at the site of Aghios...

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

If you haven’t been to the new museum at Aigai (modern Vergina) yet, you should put it immediately on your list of must-see Greek historical destinations. Northern Greece, and particularly the Veria area southwest of Thessaloniki that represents the heartland of ancient Macedonia, is a treasure trove of archaeological sites, lush landscapes and fascinating history, featuring most prominently the Temenid (or Argead) royal dynasty and its unforgettable kings Philip II and his son Alexander the Great. But what of the ladies or queens of ancient Macedonia?

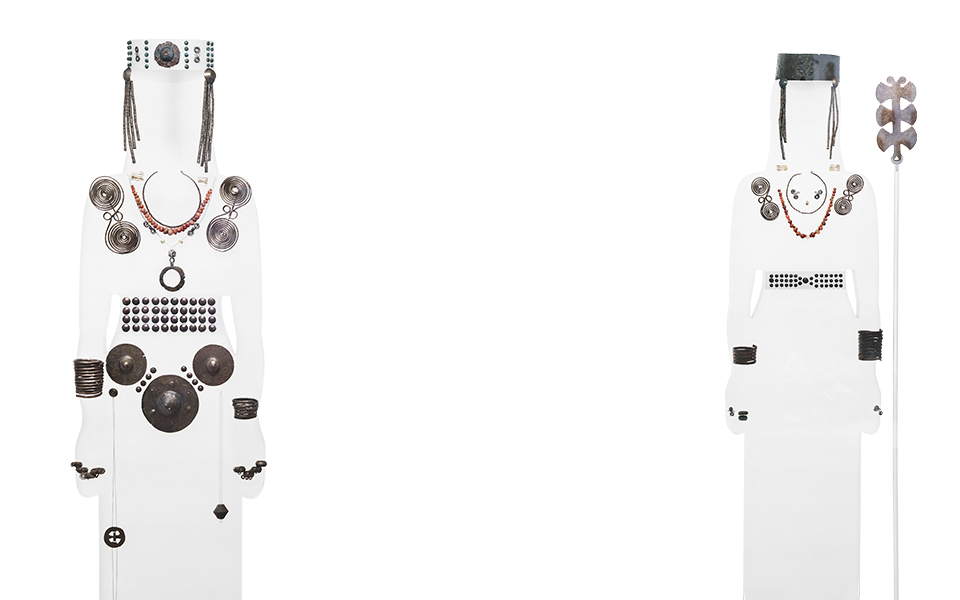

One of the most intriguing, perhaps little-considered historical revelations highlighted by the new Polycentric Museum is the presence at Aigai of clearly high-status women richly adorned with once-gleaming bronze jewelry who are presented as “Queens of Macedonia” – and who date from the early Iron Age (10th through 8th centuries BC) – an era beginning hundreds of years before the appearance of the Macedonian Temenids (about 700 BC). The exact identity or role of these ladies remains a mystery, but what they can tell us is that the splendid metals-rich culture we identify with Philip II and his empire was already a characteristic of this northern Greek region long before Philip was even a twinkle in his mother Eurydice’s eye.

The mysterious pre-Temenid "queens" of Aigai reveal that wealth and power were already a fact of life in what would become the heartland of Philip II's Macedonia.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

In the 5th century BC, Herodotus and Thucydides wrote that the inhabitants of Macedonia were descendants of Temenus, the legendary king of Argos. Their primogenitor in northern Greece was Perdiccas I, who left Argos about 700 BC, eventually establishing himself and his people “near the Gardens of Midas … in the shadow of the mountain called Vermio” – not far from the confluence of the Aliakmon and Lydias (now Loudias) rivers and present-day Veria. These were the “Macedonians,” whose name – likely deriving from “makros” in ancient Greek – meant “the highlanders” or “the tall ones.” They were hard-living mountain folk, mainly shepherds and farmers, whose elite leaders apparently based themselves at an already long-inhabited spot near a major crossroads known as Aigai, or The Place of the Goats (or Many Flocks).

Thanks to the archaeologists who have explored Aigai, led most notably in recent decades by now-retired ephor Angeliki Kottaridi, recognized today as one of the great “ladies of Aigai,” a vast necropolis of roughly 200 hectares dotted with hundreds of distinctive burial tumuli has been investigated and found to contain thousands of graves. Its southern, eastern and west/northwestern areas include Archaic and Classical tombs (6th-4th centuries BC), but at its core lies an even older cemetery dating to the early Iron Age. It is from here that the Aigai museum’s magnificently attired “queens” have once again come into the light.

From an ancient Athenian perspective, the North was a wild, largely uncivilized region ruled by an ambitious, imperially minded king, Philip II, who posed a threat to his southern neighbors. Nevertheless, this area of ancient Greece, especially eastern Macedonia and Thrace, was also known to be rich in metals – iron, copper for bronze, silver and gold – as well as timber for shipbuilding. Consequently, it became a target for colonization, as shown by Athenian efforts to establish themselves near Amphipolis in the 470s and 460s BC, and more permanently in 437 BC. Long before this Athenian push, however, the Euboeans in the 8th century BC had already installed numerous colonies, emporia and commercial ports in the northern Aegean and Thermaic Gulf region, attracted in great part by the lure of profitable trade in metals, wood and wine. The early exploitation of northern Greece by southern outsiders attests to its resources. The pre-Classical graves of the Aigai ladies confirm an obvious truth: this natural bounty had already existed and was being exploited in the early Iron Age.

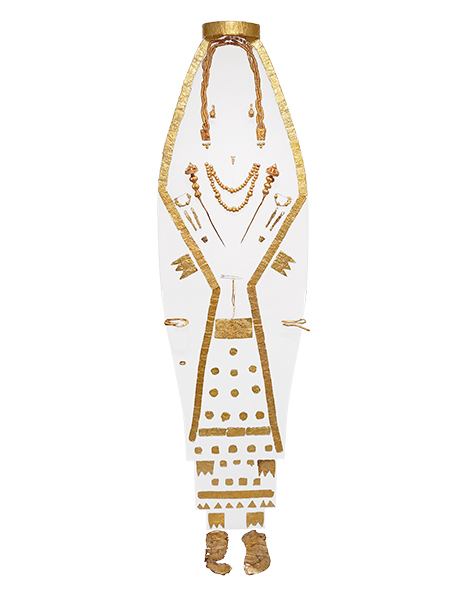

Lavish funerary adornment continued from the Early Iron Age into the Classical era.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The magnificent array of gold, silver and other luxury grave goods in Tomb II within the Great Tumulus at Aigai, purported to be the royal burial of Philip II, showcases the high level of material wealth that characterized the ancient Macedonian elite. This historic moment in the 330s BC, just before Philip was assassinated (336) and Alexander took up the imperial reins, was an apex of traditional Macedonian civilization, before the new young king changed that world radically, expanding Macedonian-borne Hellenism into far-off Asian lands.

By the time of Philip II and Alexander III, the belief that the Macedonians were originally settlers from Argos, and thus descendants of not only royal Temenus but also the mythical hero Heracles, had become tradition. In fact, it seems they were Dorian Greeks, initially northern migrants who’d spread throughout mainland Greece and had already long resided in what later became the Macedonian heartland. Their rich and diverse culture in northern Greece remained little changed over the centuries – as indicated archaeologically – from the Late Bronze Age into the early Iron Age. The Macedonians’ traditionally-held Argive origin story may well reflect a real-life Dorian “return” to the north, as evidenced by the colonization efforts of Evia, or of Corinth at Potidaea (ca. 600 BC) in Halkidiki.

Eventually, change did come to Macedonia, with the rise of the Argead dynasty, especially under Philip II, as Alexander famously reminded his rebellious troops while campaigning in Asia: “He found you wandering about without resources, many of you clothed in sheepskins and pasturing small flocks in the mountains, defending them with difficulty against the Illyrians, Triballians and neighboring Thracians. He gave you cloaks to wear instead of sheepskins, brought you down from the mountains to the plains, and made you a match in war for the neighboring barbarians, owing your safety to your own bravery and no longer to reliance on your mountain strongholds. He made you city dwellers and civilized you with good laws and customs” (Arrian, Anabasis). Philip undeniably brought changes, with military innovations – such as the lengthy sarissa spear – and greater military effectiveness, his conquest of Thrace and other outlying neighboring regions, and his consequent bestowal of greater prosperity upon his people, but clearly wealth and power were already a characteristic of the “pre-Macedonian” Iron Age elite.

Queen Eurydice I of Macedonia, whose courage and determination ultimately helped pave the way towards the Hellenistic world.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The early Iron Age ladies of Aigai were important, well-respected figures. Their personal attire and funerary accoutrements were strikingly lavish, especially compared with those of men, who were usually buried with only an occasional bronze ring or other small ornament and their iron weapons (sword, spearhead, arrowheads, or knife). Adorning the women’s heads were dangling triple-spiral bronze pendants and small golden spirals for the ends of the hair. Some wore cloth or leather diadems (now gone) with bronze buttons or other ornamentation. These noble ladies also wore carnelian bead necklaces, as well as bronze pendants, eight- or bow-shaped brooches, spiral bracelets, and rings. Their belts featured buckles, bosses and buttons. Beside them were placed tall wooden staffs capped with three double-axe heads.

Aigai’s extensive funerary evidence illuminates a complex, clan social structure necessary for effecting and controlling the exploitation and distribution of Iron Age Macedonia’s rich natural resources. The elite males were warrior kings and the females ornately clad, power-projecting queens. Kottaridi suggests the ladies, with their double-axe staffs and other ritualistic objects, also served as priestesses.

During the ensuing Archaic and Classical eras, the Temenid ladies carried on these roles, as we see from the bronze “phialai” (libation bowls) ubiquitously placed in high-status female graves, and from the embossed silver phiale of the so-called “Lady of Aigai” – identified as the wife of King Amyntas I (ruled 512-497 BC), who received a magnificent burial about 495 BC. Her grave goods of gold, silver, bronze and ivory included a gilt-edged veil, pins, jewelry, scepter, distaff, spindle and golden-soled slippers.

Two of the greatest ladies of Aigai were Eurydice I, wife of Amyntas III and mother of Philip II, and Olympias, Philip’s fourth wife and mother of Alexander. Royal succession was a crucial concern for Macedonian queens, and Eurydice, at no little personal danger and through extraordinary manipulation that even included recruiting an Athenian general supportive of her efforts, managed to ensure that her son Philip avoided murderous usurpers and became king (359 BC). Without her strength, Kottaridi reminds us, and that later of Olympias, who likely also worked behind the scenes to support Alexander, Macedonian history and Greece’s cultural impact on the ancient known world would certainly have turned out differently. Although little trace of Olympias has yet been found at Aigai, the Temenid necropolis excavations have revealed an elaborately decorated tomb with a monumental throne, discovered by Manolis Andronikos (1987), which has been attributed to Eurydice. Today, Queen Eurydice can be seen standing commandingly in one of the Aigai Museum’s courtyards, her sculpted image a votive offering to the goddess Eukleia made by the queen herself.

Archaeologists at the site of Aghios...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

Discover the lesser-known oracles of ancient...

Ten must-do experiences in Athens, from...