Thessaloniki in Autumn: Festivals, Flavors, and Street Life

Landmark shops, a lively cultural scene...

View of the Roman Agora, and directly behind it, at the corner, is the building of the Workers’ Center.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

Outside his corner shop, at the intersection of Olympou and Arrianou streets, 81-year-old butcher Vangelis Kotsabas feeds the seagulls every afternoon. It’s a ritual he’s kept for years, much like the Friday ouzo get-togethers with friends. Since 1978, when he took over the butcher shop with his brother Nikos, the neighborhood has changed dramatically. And yet, it has retained its human dimension.

“In the 1960s, apartments were mostly bought by civil servants – teachers or judges – people who paid off their mortgages with steady salaries. Every ground-floor window was a shop; the place was buzzing with life. Today, most small businesses have closed, and very few of the old customers remain,” he says, standing in front of his refrigerators.

Vangelis Kotsambas has run the butcher’s shop together with his brother, Nikos, since 1978.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

Olympou Street is one of the streets of Thessaloniki with the oldest layout.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

The shop itself opened in 1963, and the butcher who preceded him used to serve meze in an informal neighbourhood ouzeri, located where the refrigerators now stand. Buildings, of course, change function over time. Olympou’s enduring appeal lies elsewhere: in its role as a binding agent for Thessaloniki, a street that preserves the city’s continuous history while steadily absorbing new influences.

Running parallel to Egnatia Street, just to the north, Olympou connects the Rotunda in the east with the Byzantine Church of the Holy Apostles in the west, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Along its nearly three-kilometer stretch, remnants of the city’s Hellenistic core at Dioikitiriou Square coexist with the Roman Forum of the 2nd century AD, emblematic interwar buildings such as the Experimental School designed by architect Dimitris Pikionis, historic shops like the Heraklis nut store, and cafés frequented by digital nomads.

Olympou Street has fifteen listed buildings that were spared from redevelopment.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

The restaurant Limeri has been operating since 1984.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

“Olympou was one of the city’s oldest Roman decumani, streets running parallel to the sea,” explains Christina Mavini, archaeologist and museologist at MOMus (the Metropolitan Organisation of Museums of Visual Arts of Thessaloniki). “Some researchers believe it may have been the city’s main artery – a kind of early decumanus maximus – before that function shifted to Egnatia Street in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. This grid layout follows the Hippodamian system and may even date back to the Hellenistic period, though this hypothesis hasn’t been confirmed through excavation.”

She adds that significant archaeological remains once lay underground but were completely destroyed during the construction of the city’s power grid. “A major electricity cable runs beneath Olympou,” Mavini notes. She also points out that the site where the Olympia Hotel now stands housed public baths in the 1940s, offering showers to residents who did not yet have them at home.

Olga Iakovidou on the balcony of her home at the beginning of Olympou Street.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

As I stood watching the beautiful winter sunset in front of the renovated neoclassical Orestias Kastorias Hotel, I found myself thinking about what she had said regarding the street’s long history. The sky had turned violet; flocks of birds hovered above the Roman Odeon, with the monumental axis of Aristotelous Avenue visible in the distance. I took a deep breath, savoring the moment, and kept walking.

To better understand Olympou Street’s urban evolution and social fabric, I visited Olga Iakovidou, a retired professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki’s School of Agriculture. She and her husband, winemaker Vangelis Chatzivarytis, have lived on the street since 1985. The 42-apartment building divides its doorbells according to which elevator serves the apartments: right or left.

From their sixth-floor balcony – a hidden garden overflowing with all kinds of flowers – Olympou stretches below like a “green river” flowing through dense concrete. All you can really see are the trees lining the street on either side.

“My grandmother Olga’s house on Palaiologou Street was expropriated, and in exchange she was given this plot of land, one of the last available on Olympou. We handed it over to a developer in 1977, around the time of the earthquake. Our neighborhood was always working-class, especially this end of the street, which attracted a lot of students. I remember a small corner shop next door. Giannis, the owner, would gather the neighbors every Friday and throw a small feast with souvlaki,” she recalls, serving us Greek coffee and spoon sweets.

She recalls memories of other places, most now gone. “Achnos, which closed recently, had the best burger, and Limeri – with its home-style dishes – drew crowds late into the night with live music. Now it stays open only until the afternoon.”

Our photographer, Konstantinos Tsakalidis, hadn’t realized that for sixteen years he’d been Olga’s neighbor, living directly across from her. “I always wondered who had that beautiful balcony,” he says shyly, before we head out for lunch at Limeri.

On our way out, he strikes up a conversation with Iordanis Katseas, the owner of Ellada Parking next to the apartment building. We learn that construction on the building began in 1977 but was completed in 1983, delayed by changes to building regulations following the earthquake. We cross the street and sit down at the taverna so I can try its famous home-cooked dishes. The flavors are familiar to Konstantinos, especially the stuffed cabbage rolls.

White tablecloths, bain-marie trays, folk music, a warm, old-school atmosphere. “The place was opened in 1984 by my father, Sakis Gogos. I remember him getting home at two or three in the morning and leaving again early at dawn. We still have customers who ate here as students and now bring their children,” says 39-year-old Thomas Gogos, the current owner.

Dina Sideri, owner of the Alex cinema and the neighboring flower shop.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

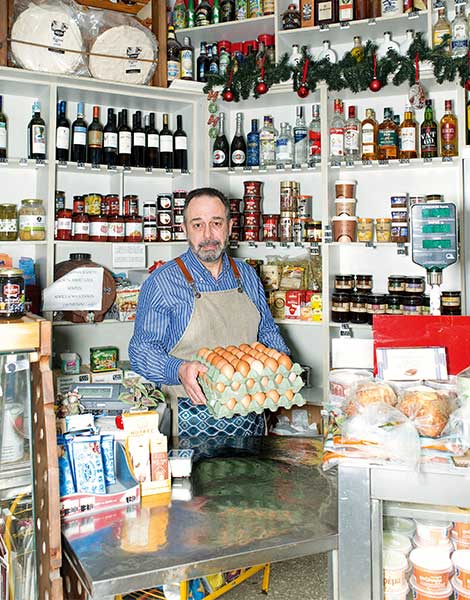

At his grocery store, Giorgos Ouzounis sells eggs from Neochorouda.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

Next door to Limeri is Elena Tsegkeli’s children’s clothing store. On the shop window beneath her desk, she’s displayed one of the first rent receipts, dated 1979. Just a few steps further down, past Iasonidou Street, stands one of Olympou’s fifteen listed buildings: the Alex open-air cinema.

“My parents acquired the building in 1957. Originally, it was a lumber yard and ice storage. In 1968, we opened the cinema and four years later we converted the remaining space into a flower shop. Across the street, where the 34th Primary School is today, there used to be an open lot known as ‘Voulgariko,’ and Iasonidou Street was still unpaved. Olympou was a street of many micro-neighborhoods. For example, the stretch from Eleftheriou Venizelou to Andrea Kalvou featured mostly clothing and shoe workshops, along with numerous repair shops,” explains Dina Sideri, owner of both the cinema and the flower shop.

I head west towards Giorgos Ouzounis’ grocery store. A local institution, it has supplied the neighborhood with eggs from Neochorouda, a farming village on the outskirts of Thessaloniki, along with yogurt, select cheeses, and countless other delicacies since December 1990.

Dimitris Angelis at the record library of Pikap.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

Along the way, an electrical repair workshop caught my eye. Craftsmen still thrive on this street which, according to journalist Dimitris Ioannou, author the Time Out segment on Thessaloniki, “the city’s historic elegance meets vibrant, student-driven energy.”

“My father came here in the early 1980s. I joined the business in 2014, at 23. There are very few shops like ours left, so we have customers from all over Greece,” explains owner Kyriaki Kehlibari. Sitting behind an old wooden desk topped with marble, she offers me a spoonful of varvara, a traditional sweet, and continues: “Across the street, the restaurant Kits kai s’ Efaga used to be a flower shop with a dry cleaner’s next to it.”

The gradual transformation of Olympou – always popular with students and the shops that cater to them – began with the opening of the café-bar Frederiko Agapi Mou.

“At the time, the neighborhood was really run down,” recalls Dimitris Mikos, who co-owned the venue before it was sold in 2017. “We wanted to attract people from the city center, who tended to dismiss anything north of Egnatia Street. In a way, we brought the spirit of our other café, Pastaflora Darling, on Zefxidos Street.”

His account is echoed by Dimitris Vlasios, a longtime local resident who once worked behind the bar there. “Fifteen years ago, the street was abandoned, even dangerous in places,” he says. In September 2024, together with chef Vasilis Hamam, Vlasios opened ESTET Café, right next to Tsarouchas, the legendary 24-hour patsatzidiko that has been operating on the same spot since 1967.

On one side of the street, night owls seek comfort in a steaming bowl of soup; on the other, one finds the eclectic junk shops of Bit Bazaar. Between them sits ESTET, serving coffee and grilled sandwiches in the morning, cocktails by early evening, and welcoming people of all ages: locals, digital nomads, tourists in short-term rentals, and Thessalonians from other neighbourhoods drawn by the street’s energy. Even amid the visual overload of posters and graffiti, Olympou remains undeniably one very cool street.

At the café, I also meet journalist Despina Polychronidou, who moved to Olympou 12 years ago, back when rents were still affordable. I mention what I was told at the Square Meter real estate agency further up the street: rents have risen by 40 percent over the past decade. She confirms it with a nod.

“It’s become fashionable. In the evenings, especially after performances, you’ll run into well-known actors strolling along Olympou. Of course, the metro has also pushed prices up. Still, compared to the rest of the city, rent prices remain relatively accessible,” she says.

She likes Olympou, she tells me, because it’s full of surprises and contrasts, like the Thessaloniki Labor Center, the underground theater lounge of Politeia Theatrou, and Pikap, a café-bar, record library, radio station, and exhibition and concert space that has been a local cultural hub for the past decade.

I ask Dimitris Angelis, co-owner of Pikap, what gives the street its relaxed, welcoming vibe. “First of all, there are places where you can truly settle in, under the trees or inside one of the shops,” he explains. “These spaces are made with care. People with shared interests naturally come together here, and newcomers – no matter how unconventional their ideas – are absorbed almost magically. No one tries to impose themselves.”

Antonis Fotiadis in the kitchen-theater Aspo Dentro.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

Journalist Despina Polychronidou, a resident of Olympou Street, guided us through her neighborhood.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis / SOOC

Indeed, Olympou is a street that invites bold projects. In 2019, near the Church of the Holy Apostles – now one of the city center’s most popular neighborhoods following redevelopment – Antonis Fotiadis opened Aspro Dentro. The venue comprises a restaurant, a theatrical stage, and a yoga-and-dance studio.

“Ten years ago, this place was empty. Before that, it was a well-known jeans factory,” Antonis recalls. With a background in both cooking and the theater, he remembers a neighborhood dominated by auto repair shops and mechanics. “They were selling engine oil right next door.” Very few of those workshops remain today. Still, this stretch – from Karaoli kai Dimitriou to Andrea Kalvou – remains less developed than the rest of Olympou, though that is gradually changing.

At the corner of Gladstonos and Olympou, a former tobacco warehouse has recently been transformed into Tabac, a new modern building by Project 151. The complex comprises 72 fully furnished contemporary rooms and offers a full range of amenities, including laundry facilities and a gym. It caters primarily to students – continuing Olympou’s long-standing relationship with student life – as well as young professionals.

Just a few steps further west, the Laspi ceramics studio opened its doors last March. “I came here partly for the affordable rent, but also because this part of Olympou is on the rise,” says ceramic artist Thei Mouratidou. “In summer, there was plenty of foot traffic and tourists. In winter, it feels much quieter.” As we speak, the persistent buzz of electric welding fills the air: another short-term rental property is being developed nearby.

Across the street, almost all ground-floor shops have been“converted into accommodations; a familiar symptom of neighborhoods adapting to tourism. Refusing to dwell on the possibility of Olympou becoming an endless corridor of rolling suitcases, I close my eyes and recall the words of Deputy Mayor for Technical Works and Sustainable Mobility Prodromos Nikiforidis, who has proposed integrating the street into the city’s unified network of archaeological sites.

“In the coming period, work will begin on rebuilding Olympou’s sidewalks, widening them where possible. Ideally, Olympou would become a pedestrian street, something we unfortunately can’t implement at this stage.” But just imagine it: Olympou, a pedestrian-only street, alive with history, cafes, and creativity: a vision that feels entirely possible on this remarkable street.

Landmark shops, a lively cultural scene...

From the fall of a monarch...

A Thessaloniki expert selects 13 spots...

Six creative Thessaloniki locals share their...