The Armata Festival and the Allure of Spetses...

Experience Spetses in its most enchanting...

The Firkas Fortress and its barracks.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Behind the counter of a modern cosmetics shop, a section of the Venetian wall that once lined the city’s southern moat comes into view. Several meters north, beneath racks of clothes and souvenirs, box-shaped tombs from the period of Venetian rule (1204–1645) lie embedded in the floor of a tourist shop. Welcome to Hania’s Old Town: a living museum defined by the boundaries of its once-mighty fortifications, where history reveals itself in the most unexpected places.

Beyond the defensive walls – constructed between 1538 and 1568 in response to the threat posed by the Ottoman Empire and the raids of the pirate Barbarossa – the area holds a wealth of Venetian buildings. Today, these structures serve diverse roles: some function as cultural venues, others as monuments in various stages of conservation, while many have found new life as guesthouses, cafés, or boutiques.

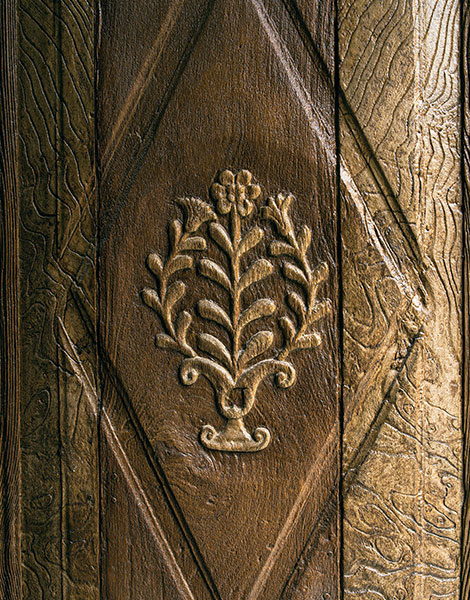

Detail from the door of the Rector’s Palace.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The Neoria have been incorporated into a restoration project with a budget of around 21 million euros.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Whether in the form of scattered archaeological finds or grand architectural structures, Hania’s Venetian heritage adds a cosmopolitan flair to the city. In certain places, it even creates dramatic backdrops of striking beauty. Yet this same legacy also bears the scars of neglect and destruction; reminders of how easily cultural heritage can be diminished over time.

In 1903, a decree by the then-independent Cretan State handed the city’s fortifications over to the Municipality of Hania, with plans to demolish them and repurpose the land for public use. Thankfully, this effort to unify the old town with the newer settlements that had spread beyond the walls resulted in only limited demolition, mostly affecting the southern section. One notable example is the city’s cruciform Municipal Market, built in 1908 atop the imposing Piatta Forma bastion. Ironically, rubble from the demolished walls was used to fill in the surrounding moat.

The tales of architectural incongruity – or urban “madness,” as many call it – in Hania’s Old Town don’t end with the Venetian walls. Despite the area’s official designation as a historic monument in 1965, large sections of the southern moat were handed over to private owners and built up with apartment blocks. At the same time, makeshift homes began to appear along the ramparts, often on land unofficially allocated to impoverished residents for use as gardens.

As you walk down Mousouron Street today, you might never guess that, had the wall remained intact, you would eventually reach the Retimiota Gate – Kale Kapısı in Ottoman Turkish, or “fortress gate.” Even now, residential buildings press directly alongside the remnants of the walls, and some sections of the old moat continue to be misused as informal parking lots.

View of the Mocenigo Bastion from Koum Kapi.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Despite these setbacks, approximately 85% of the original fortifications have been preserved, and the total area of the three remaining moats amounts to roughly 19 hectares. “A number of studies are currently underway, aimed not only at conserving and highlighting these historic structures, but also at reimagining them as vibrant public spaces for residents and visitors alike,” says Eleni Papadopoulou, Director of the Hania Ephorate of Antiquities.

One key example is the ongoing planning for the eastern moat, which currently serves as both an event venue and a car park. While many important proposals have been approved for monuments throughout the Old Town, the most ambitious project to date is the “Restoration, Enhancement, and Repurposing of the Seven Venetian Neoria,” located at the heart of the old Venetian harbor – a €21 million initiative already in progress.

In the foreground, the San Salvatore Bastion with the western moat beside it.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Once used as shipyards and storage facilities, these iconic vaulted buildings are set to become cultural spaces. “Together with the adjacent Grand Arsenal, which houses the Center for Mediterranean Architecture, and the nearby ‘Mikis Theodorakis’ theater,” explains Giannis Giannakakis, Hania’s Deputy Mayor for Culture, “they will form a major cultural platform with the real potential to become a central hub for the arts, not only in Greece but across the Mediterranean. No other site in the country brings together such a rich and layered complex of cultural significance.”

The adaptive reuse of Venetian buildings is nothing new in Hania. Following the Ottoman conquest of Hania in 1645, nearly all of the city’s Venetian buildings were repurposed, often multiple times and for radically different functions. The Grand Arsenal, for instance, originally built as a shipyard, served as a warehouse during Ottoman rule. It later housed the Christian community’s school and then the public hospital. In the interwar period, it became the City Hall, before falling into disuse until its restoration in 1998.

On the eastern side of the harbor, three more Venetian arsenals have survived. These buildings were named after Moro, the Venetian Governor who oversaw their construction. Today, they host a variety of institutions: the Hania Sailing Club, a conservation workshop run by the local Ephorate of Antiquities, and the Maritime Museum of Crete. The latter includes a faithful reconstruction of a Minoan ship on display.

The ground floor of the Grand Arsenal hosts exhibitions.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Beyond the harbor – with its fortified bastion of Aghios Nikolaos of the Mole (now used as a venue for civil weddings) – the inner layers of the Old Town are also home to important Venetian landmarks.

Our tour with Giannis Fantakis, contract archaeologist with the Hania Ephorate of Antiquities, began on the western side of the town, which, unlike the east, was spared the bombings of German aircraft in 1941. Leaving behind the bastion of Aghios Dimitrios, now home to Hania’s 2nd Primary School, we walked north along the embankment of the western wall.

We passed through wildflowers, tall grasses, and the occasional shack, eventually reaching the outwork of Aghia Aikaterini, which still features a German pillbox built during the Second World War. From this elevated position, we could see the San Salvatore Bastion – named after the adjacent monastery – and the old Venetian powder magazine.

Part of the Monastery of Our Lady of Miracles in Kastelli.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The Church of Aghios Rokkos in Splantzia.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

This neighborhood is known as Topanas, a name derived from the Turkish word top-hane, meaning “arsenal” or “gunpowder store.” Inside the former ammunition warehouse, we met art conservator Giorgos Siganakis, who was delicately cleaning a 19th-century religious icon. “This building has served as the conservation lab for icons under the Hania Ephorate of Antiquities since the mid-1970s,” he told us. Siganakis himself has worked with the department since 1994.

Directly across stands the Monastery of San Salvatore. Its church has housed the Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Collection of Hania since 1997. The monastery’s cloister still survives, and the former monks’ cells have been converted into private homes and tourist accommodations.

Continuing along Angelou and Antoniou Gampa Streets, both lined with preserved Venetian townhouses, we felt momentarily transported to Venice itself. Eventually, we reached the Firkas Fortress, completed in the early 17th century. It was here, on December 1, 1913, that the Greek flag was raised to mark the official union of Crete with Greece.

Two features stand out in this fortress complex, which once housed military barracks and ammunition depots, and served as the headquarters of the island’s military commander. First is the circular Genoese tower at the western edge of the courtyard, an earlier structure that was incorporated into the fortifications in the late 16th century. The second is the emblem of the Venetian Republic: the lion of Saint Mark, prominently carved into the two-story barracks building. Today, the main structure of the fortress also houses the core collections of the Maritime Museum of Crete.

One of Moro’s three Neoria houses the Ηania Sailing Club.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Tasos Gourgouras prepares his tourist accommodation in the Rector’s Palace for the season, as the historic building has been divided into several properties.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Our tour of the Old Town with Giannis Fantakis lasted nearly five hours. The deeper we wandered into its narrow alleys, the more vividly the Venetian past of Hania came into focus. At the arched entrance of the Renier Mansion, built in 1608, we saw the family’s coat of arms alongside a Latin inscription: “Much did the gentle father bring, do, and ponder; he toiled and he sweated. May eternal peace shelter him.”

Nearby, on Kastelli Hill, we visited the 16th-century Rector’s Palace and tried to imagine the life of the Venetian governor who once resided there. There, we met 60-year-old Tasos Gourgouras, preparing his apartment – one of several that now occupy what was once a single medieval structure – for the season’s first guests.

Passing through the Sabbionara Gate, we entered a digital installation offering a virtual tour of Old Hania. At the former Catholic church of the Monastery of Saint Francis, home to the city’s Archaeological Museum until 2020, we were struck by the interplay of Ottoman and Classical Greek artifacts on display in the surrounding courtyard.

Our walk ended in Splantzia Square, where we stopped for lunch between two symbolic buildings: the Church of Aghios Rokkos, protector of Hania during the plague, and the Church of Aghios Nikolaos, the only church in Greece to feature a bell tower on the left and a minaret on the right.

This, ultimately, is what Hania offers: a quiet journey through time that teaches the values of coexistence and cultural diversity. But it also asks something of the visitor: the willingness to look past the wounds of history, and to see the enduring beauty of a city shaped by centuries of layered heritage.

Experience Spetses in its most enchanting...

This short walk takes in eleven...

Discover Greece’s islands in September with...

Where tropical fruit trees thrive beside...