Disability in Ancient Greece: Myths, Facts, and Accessibility...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

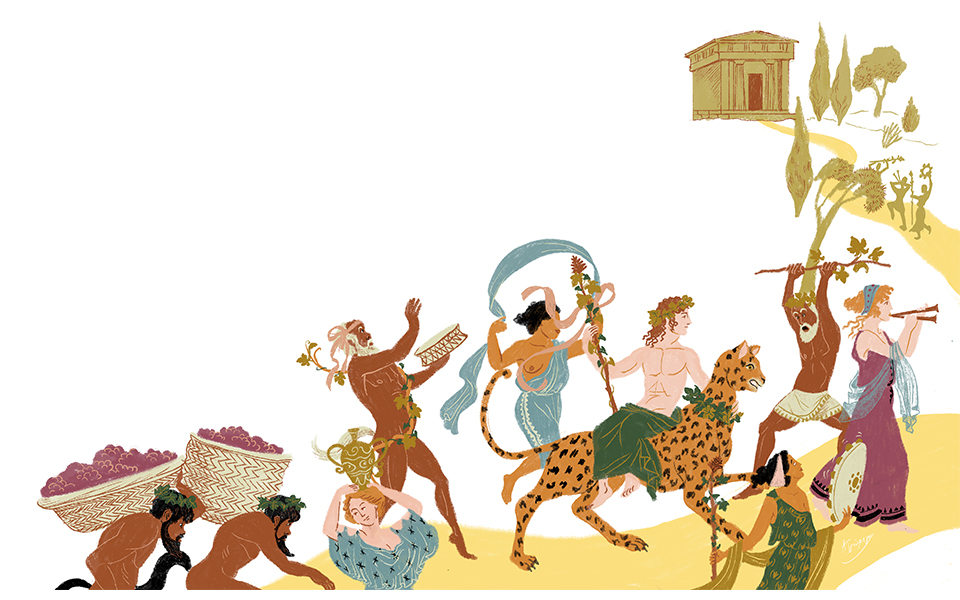

© Illustrations: Anna Tzortzi

The ancient Greeks’ complex pantheon and rich repertoire of myths and heroes remains a timeless, beloved subject. One of the favorite exhibits in the Acropolis Museum is a humble pair of modern reconstructions of the Parthenon’s east and west triangular pediments with their myth-related sculpture groups, located in the vestibule of the top-floor Parthenon Hall. Visitors can regularly be seen flocking around these small-scale models, trying to distinguish who the diminutive sculpted characters are and to make out the story they are telling. Clearly recognizable are Greek gods, goddesses and other mythical beings, here portraying the Birth of Athena and the Contest between Athena and Poseidon. But what did these divine figures actually mean to the ancient Greeks? And what was the cultural or societal importance of their collective narratives? The nature of such questions goes to the very heart of archaeology, history and art history.

In present-day studies of ancient Greece, impressive architectural remains and archaeological artifacts on their own are not enough. What we really want to understand is how ancient people lived, what they were thinking, and how they felt about and reacted to their world. Anthropomorphic sculptures in particular, such as those of the Parthenon’s pediments and frieze, seem to stir our curiosity, as ancient Greeks and their gods look so much like us, so identifiable, often dealing with many of the same life issues and problems that we do. Their world was markedly different, however, separated from ours by two millennia, with distinct cultural values, ideas and beliefs, all operating in a natural environment far more pristine and integral to daily life than our own. In the realm of religion, virtually everything in an ancient Greek’s surroundings was perceived through the lens of the gods: divine spirits who dwelt and freely roamed among their mortal dependents, governing, protecting, influencing and enriching the human experience.

© Illustrations: Anna Tzortzi

Although today we recognize that the central pillars of the ancient Greek pantheon were the Olympian gods – Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Athena, Demeter, Aphrodite, Ares, Apollo, Artemis, Hephaistos, Hermes, Dionysus, and possibly Hestia – these familiar deities were universal in Greek culture primarily in the sense of their being Greek, as opposed to foreign, non-Greek gods. That is, from the outside looking in, the Olympians appeared to be general figures worshiped commonly by Greeks. However, inside the Greek cultural sphere, the gods were mainly characterized throughout the Greek world’s disparate regions not by commonality or uniformity, but by specificity and diversity. Just as ancient Greece was a geographical area of distinct, varied terrain, so too were its peoples, within their respective regions and city-states, diverse in their self-determined ethnic and political identities. Thus, within each community, the citizens had their own gods, goddesses and heroes that were considered distinct from those of their neighbors and belonged to that community.

Gods were “shared” figures only at specific places and under specific circumstances – particularly in Panhellenic sanctuaries, such as Olympia and Delphi, where Greeks from far and wide gathered, worshiped together, and sacrificed to each other’s gods on the same altars.

On a civic or state level, every city had their own divine patron that protected the city-state and encouraged its people. In 5th-century BC Athens, for example, Athena was the great patroness. In Sparta, it was Artemis and Apollo; in Thebes, Dionysus and Apollo; in Argos and Samos, Hera. For the Athenians, Athena supported and represented (through her own attributes) their various interests, ambitions and industries. As the warrior goddess, she emboldened the city-state’s military and imperial aspirations. As the goddess of wisdom, she inspired the city’s sage philosophers and other thinkers. Through her vital gift of the olive tree, meanwhile, she promoted Attic agriculture by encouraging farmers to cultivate a remarkably versatile crop. The olive tree provided not only nourishing fruit and calorie-rich oil but also fuel for lamps and wood for winter fires. Olive oil, in particular, was indispensable: athletes and others used it for personal hygiene; physicians for healing remedies; and early pharmacists and perfumers for cosmetics, unguents, and aromatic scents. It was also a key commodity for trade, and it played an important role in religious rituals: in the anointment of kings, of gods in mythology, and of the dead before burial.

© Illustrations: Anna Tzortzi

No wonder the olive tree, with all its practical benefits for Athenians, featured prominently in the mythical contest between Athena and Poseidon over who would become Athens’ patron deity. The sea god’s gift of brackish spring water could not measure up to Athena’s arboreal offering. As ancient visitors ascending the Acropolis emerged from the Propylaia, Pericles’ sculpturally adorned Parthenon rose before them, crowned with its triangular western pediment showcasing Athena’s victory. Directly ahead also towered Pheidias’ 9m-tall bronze statue of the warrior Athena (“Promachos”), who had recently aided the Athenians in suppressing the Persians. The 2nd-century AD traveler Pausanias reports: “The point of the spear of this Athena and the crest of her helmet are visible to those sailing to Athens, as soon as Sunium is passed.”

Poseidon, however, held pride of place not only beside Athena in the Parthenon’s pediment, but also in the adjacent Erechtheion, the singular Periclean temple that gathered the Acropolis’ main traditional cults under one roof. Pausanias again relates: “Before the entrance is an altar of Zeus the Most High … Inside the entrance are altars, one to Poseidon, on which … they sacrifice also to Erechtheus, the second to the hero Boutes, and the third to Hephaistos.” Poseidon was revered in Athens – as at Corinth and Isthmia, coastal locations – due to the sea playing a major role in daily Athenian life, political and naval outreach, and economic activity. His most prominent temple stands in southern Attica, high on Cape Sounion. Erechtheus was the legendary king and founder of Athens, whose divine father was Hephaistos. Boutes’ recognition stemmed from his being the heroic eponymous ancestor of the Boutadai and Eteoboutadai, noble Athenian families that provided the priestesses for the cult of Athena Polias (of the City). Adjoining the west side of the Erechtheion was a shrine to Pandrosos, a daughter of Athens’ mythical king Kekrops, who had been entrusted by Athena with safeguarding the infant Erechtheus.

State cults on the Acropolis also included the worship of Artemis Brauronia, from Brauron in east Attica, who was given her own small sanctuary just south of the Propylaia. Artemis was revered in Athens as the goddess of good counsel; sacrifices were offered to her before every meeting of the Ekklesia (“People’s Assembly”). Athena Nike (“Victory”) similarly had a small temple above the Acropolis entrance. She represented, and her temple’s sculpted decoration commemorated, Athens’ military might and great triumphs.

Around the Acropolis, numerous other deities were worshiped by ordinary Athenians in small open-air sanctuaries and caves. The people of Athens, Pausanias observed, “are far more devoted to religion than other men.” Shrines on the South Slope included those of Aphrodite Pandemos (“Of All the People”), Nymphe (a local protectress of marriage and wedding ceremonies), Asclepius (god of healing), and Dionysus (god of wine, religious ecstasy and theater). The sanctuary of Asclepius with its sacred spring also marked a spot, as indicated by an inscription (1st century BC), where honors were given to Hermes, Pan (god of the wilderness and of pastoral music), Aphrodite (goddess of erotic love), the Nymphs (representing nature), and Isis, a Hellenized Egyptian goddess of mourning and magical healing. The Dionysus Theater was only one part of the god’s sanctuary, which included a small temple and altar. On the North Slope were caves sacred to the Furies (deities of vengeance), Pan, Zeus Olympios, Apollo Hypoakraios (“Under the High Rocks”), Aphrodite Ourania (“Heavenly”) and Eros (god of love). On the east side, in the largest of the Acropolis caves, was the shrine of Aglauros, another of Kekrops’ daughters, who’d sacrificed herself for the city.

© Illustrations: Anna Tzortzi

In the Athenian Agora, the city’s central square and marketplace, archaeological excavations have unearthed about 300 figurines of Aphrodite, as well as jewelry adorned with depictions of ever-popular Eros. A wide range of other objects and structures also illuminate the importance of the gods and their regular role in ancient daily life. Temples and stoas were dedicated to Apollo Patroos (“Fatherly Protector of the People”), Zeus Eleftherios (“Liberator,” “He Who Gives Bountifully”), Ares (god of war), and Demeter (goddess of the harvest and fertility). On the Acropolis and in the Agora, statuary, reliefs carved on steles, painted vases and wall paintings depicting gods were common signs of devotion. Large statues of Apollo and Themis (“Justice”) have been found in the marketplace, while Hermes (god of trade, commerce, thieves and travelers) was a particularly favorite subject on painted containers. Numerous herms (steles featuring Hermes’ head and male genitalia) marked the area of the crossroads (“The Herms”) at the Agora’s NW corner.

Hestia (goddess of the hearth) was worshiped with Zeus in the Bouleuterion (Council House). The adjacent Old Bouleuterion became the Metroon (late 5th century BC) – a shrine to Rhea, mother of the gods, who was the protector of Athens’ Boule (Council of 500) and its city archives. In the nearby Stoa of Zeus Eleftherios, Pausanias saw a mural depicting divine Demokratia (“Democracy”) and Demos (“People of Athens”), as well as a statue of Eirene (“Peace”) holding the infant Ploutos (“Wealth”) near the monument to the Eponymous Heroes, symbolic representatives of the ten Attic tribes.

Demokratia also appeared in a relief-carved scene at the top of a stele inscribed with a decree against tyranny passed in Athens following the Macedonians’ victory at Chaeronea (338 BC). Discovered beneath the Stoa of Attalos, the relief shows the goddess placing a crown on the head of Demos. It was probably knocked down in 322 BC when the Macedonians eventually seized Athens.

In public, Hestia was worshiped in the Prytaneion in particular, a multi-purpose building that served as the Archons’ official residence and provided VIPs with meals at state expense. It also held the city’s symbolic central hearth and ever-burning sacred fire. Statues of Eirene and Hestia were placed there, according to Pausanias. Despite archaeologists’ past uncertainty, the Prytaneion is believed today, based on convincing new evidence, to have stood east of the Theater of Dionysus and Cave of Aglauros, beside the Street of the Tripods, near Athens’ original pre-Classical agora.

Altars for offerings and sacrifices were another common feature in Athenian public spaces, located primarily outside temples. The Altar of the Twelve Gods, near the Agora’s northwestern Zeus stoa, stood inside a small walled area so respected by authorities and the public that it served as a place of asylum for supplicants and refugees. In the later Roman Agora, Pausanias informs us, were four altars of Eleos (“Mercy”), Aidos (“Shame/Modesty”), Pheme (“Rumor”), and Horme (“Impulse/Effort”).

The Temple of Hephaistos, on the western hill overlooking the Bouleuterion, marks a district once inhabited by Athens’ metalworkers, whose divine protectors were Athena Ergane (patroness of artisans) and Hephaistos (god of the forge). Both deities were worshiped in the Hephaisteion, each with their own cult statue in the cella; the heroes Herakles and Theseus were prominently displayed on the temple’s eastern metopes. Theseus also appeared in wall paintings in the Painted Stoa and the Stoa of Zeus Eleftherios, and had his own sanctuary east of the Acropolis somewhere near the Prytaneion.

More than one hundred days were designated as sacred or festival days in ancient Athens. The first eight days of each month were dedicated to particular deities or heroes, including the Agathos Daemon (“Good Spirit”), Athena, Herakles, Hermes, Aphrodite and Eros, Artemis, Apollo, Poseidon and Theseus.

Among Athens’ major and minor festivals were the Plynteria and Lesser and Greater Panathenaia (for Athena); Boedromia (for Apollo); Adonia (for Aphrodite and Adonis); the Lesser and Greater Eleusinian Mysteries; Thesmophoria (for Demeter and Persephone); and Epidauria (for Asclepius). There were also the Rural and City Dionysia, Lenaia, Anthesteria (for Dionysus); Diasia and Olympieia (for Zeus Meilichios and Zeus Olympos); Elaphebolia (Artemis); Thargelia (Apollo, Artemis); and Diisoteria, an end-of-year celebration for Zeus Soter (“Savior”) and Athena, with a final thanksgiving sacrifice to Zeus and a welcoming of the new year on the last day. Each festival had its own meaning and special rites. Activities included processions, ritual purification and sacrifices, wine-drinking, wreath-making, preparing special cakes and other foods, athletic games, theatrical contests, horseback-riding contests and regattas off Piraeus.

When not erecting votive statues or making other offerings in sacred or public spaces, Athenians and other ancient Greeks followed their beliefs privately within their households. Diversity ruled here as well, since each family worshiped their respective ancestors and had their own preferred family cults. The father was essentially the family priest, while women might serve as priestesses and cult attendants outside the home. Domestic devotion centered on the family hearth and fire, although revered images and shrines were customarily placed at various key points in or around the house and family property. Prayers, votive offerings and sacrifices were made at small altars, using figurines and other representations of those being honored. These acts sought divine favor regarding the family’s health, births, deaths, marriages and continued well-being.

Besides Hestia, household gods included Zeus Ktesios, Zeus Meilichios, and the Agathos Daemon – deities associated with protecting family prosperity and often chthonically symbolized by a snake – a not-uncommon sight around ancient homes. Zeus Ktesios might also be invoked via a “kadiskos,” a small two-handled sacrificial jar filled with household foodstuffs. The Agathos Daemon occasionally appeared in art as a young man carrying a cornucopia or other items symbolic of fertility. Before and/or after meals, libations were made to Hestia, Zeus Soter, the Agathos Daemon, or Dionysus.

Outdoors, tutelary images of Zeus Herkeios (“Protector of the Courtyard”) were placed between the house and its enclosing wall, while Hermes (protector of doorways), Hekate (protector of crossroads), and Apollo Agyieus (“Protector of the Streets”) had small apotropaic shrines at the gate or in front of the house.

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

On the city’s eastern edge lies...

Before passports and package tours, pilgrims...