Paros: 12 Culinary Stops on a Cycladic Favorite

From kafeneia serving souma and meze...

View of Kampo, with the Church of Panagia Syriotissa in the foreground.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

A giant screen glows pink through the dense foliage of the orange grove, creating confusion in both mind and senses. Where once you would see workers harvesting fruit, a new kind of landscape has emerged – a digital one. Scattered across the 30-acre Karavas Estate are sculptures and ceramic works, installations, and even a reconstructed garden. These works, created by 12 artists, explore the theme of decay as part art exhibition Once We Were Gardens, organized by the contemporary art organization DΕΟ on the occasion of its 5th anniversary.

“It’s about how we respond to decay – of ideas, of the mind, of the body, of relationships, of space,” explains Akis Kokkinos, curator and founder of DΕΟ. “The works enter into dialogue with each other and with the estate itself, addressing the tension between preservation and transformation.”

Life, decay, preservation, and transformation: these timeless themes echo through Kampos itself, a region just beyond the city of Chios that feels like a world apart. Made up of a patchwork of grand estates, Kampos is a gifted landscape that gave rise to a unique culture, one that brought together farmers, townspeople, and shipowners in a rare blend of land and art, austerity and wealth. Here, everything seems to coexist in quiet equilibrium. It’s a place characterized by mystery and seclusion.

Narrow streets barely wide enough for a car, tall stone walls, and fragrant flowers — that’s what a walk through Kampo is like.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

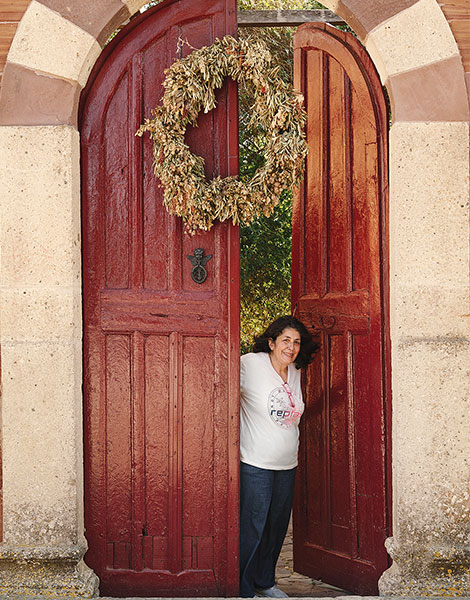

Akis Kokkinos, curator of the exhibition Once We Were Gardens by DΕΟ.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Beginning with the Genoese, who were the first to bring citrus cultivation to the island (Kampos is considered the very first place in Greece where citrus trees were grown), the area has always been defined by the estates of wealthy, cosmopolitan merchants: initially Genoese and later Chian, during and after the Ottoman period.

The true golden age of citrus, however, came in the 19th century. The estates were overseen by the anestates: caretakers who were compensated not with wages, but with lodging and the right to profit from the fruit harvest. Acres of citrus groves surrounded grand mansions, their ochre-colored façades built from local Thymiana stone and their arched gateways turned away from the narrow dirt lanes which were just wide enough for a cart to pass. Any wider would have cost valuable orchard space; every extra tree meant added income.

High stone walls and rows of cypress trees concealed the wealth within: exquisite gardens, ornate manganopigada (water-lifting devices), wells and cisterns that formed a remarkable irrigation system, as well as pebble mosaic courtyards, marble staircases, family crests, painted ceilings, and furniture brought from around the world.

Vangelis Xydas, the driving force behind the Perleas Guesthouse and the Tziradiko Estate.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The spouts that poured water into the basin were shaped like lions or snakes. Here, at the Karaviko Estate.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

By the late 19th century, the oranges of Kampos were as precious as jewels. Workers used special shears to harvest a precise quota; cut more, and they would be dismissed. The same fate awaited those whose fingernails were not well kept, as even the slightest scratch on a fruit was unacceptable. Each orange was wrapped individually in paper – sometimes even in gold-printed wrappers – carefully stacked in special crates and shipped to distant lands as luxury goods. It is said that in Russia a single orange cost a full day’s wage and was the most treasured Christmas gift parents could give their children.

The mandarin, extremely popular today, was introduced to Chios from China in 1850. for its resilience to the cold. It was a direct response to the devastating kaftria, a frost that plunged temperatures to -23°C and wiped out most of the region’s orange trees.

Today, this once-vast green sea of 14,000 acres has shrunk considerably. Citrus cultivation sharply declined after the 1980s, when Greece joined the Common Agricultural Policy and exports ceased. According to the Ministry of Culture, around 200 estates remain, with approximately 40 mansions still inhabited, many officially listed as protected historic monuments.

The most magnificent mansions and churches had pebble-paved courtyards, true works of embroidery.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Atmosphere extends indoors as well. Here, at the Astrakia Guesthouse.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

In Kampos, privacy is more than a preference; it’s a way of life, seemingly stitched into the landscape and mindset of its people. Even today, the ethos of seclusion remains strong. There are no public squares here; Kampos may be the only settlement in Greece without one. Even the churches were once privately owned. If the people of Chios are known for their reserve, those of Kampos are famously even more guarded.

“The wall mentality prevails here – introversion and elitism. Of course, it’s no longer justified, since the old wealth is gone; only the backdrop remains,” says Vangelis Xydas, one of the last anestates of Kampos and the driving force behind Perleas Guesthouse, which he created in 1992 on the Tziradiko Estate, inviting visitors into the cloistered world of Kampos’s orchards and mansions.

It was his mother, Ioanna, who first opened a guesthouse in Kampos in 1982: Perivoli, located within the Lykiardopoulos (or Karalis) Estate. Today, the same site is home to the beautiful Citrus Museum, founded by Vangelis Xydas, Giorgos Plakotaris and the John S. Fafalios Foundation, which supports cultural initiatives on the island. Together, the same team launched the Citrus company, which operated on the estate from 2008 until 2020 (now relocated to Athens under Stamos Fafalios), playing a crucial role in introducing Kampos’s legendary “mandarin-oranges” to markets across Greece, alongside the work of the local Kampos Chios factory.

Detail of a water well.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The imposing courtyard gate of the Kalvokoresis Estate.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Today, Perivoli continues that tradition. Under the care of Klaeri Tsitsopoulou, the estate produces artisanal sweets and marmalades, while its garden now hosts a charming café of the same name. In the hands of Vangelis’s son, Odysseas Xydas, the estate has become a rare symbol of openness in a place known for its closed gates.

“I call Kampos a ‘sleeping giant.’ I see it as an uncut diamond. But the mentality in Chios needs to change. You can’t expect Chian mandarins to compete with supermarket fruit. Kampos is something else entirely – each piece of fruit is handled with care. It raises costs, but the result is incomparable. There’s real potential here – for cultivation, for processing, even for agritourism, especially in winter. But it takes effort, vision, and proper marketing,” says Odysseas.

That same vision fuels Anneza Klouva, a young woman who grew up among her father’s orchards and returned to them after studying economics. She chose to take over the family’s organic farming operation, convinced that Kampos has no future without active cultivation. Working independently, she secured partnerships with major Greek supermarket chains, leveraging the PGI (Protected Geographical Indication) status of the Kampos mandarin. She now champions the idea that the region’s orange, unjustly sidelined due to its seeds, deserves the same recognition.

The ‘andréses’ at the Citrus Museum. They were used to mark the shipping crates with the sender, destination, type, and quantity of the product.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

One of the most historic mansions of Kampos is the Antouaniko, which in 2015 received the Europa Nostra Award for its exemplary restoration, carried out by architects Manolis Vournos and Katerina Manoliadi. Built in 1893 by Dimitrios Tetteris (Antouanos was his son), it contains sections that are even older, such as the cistern with its original pillars, the stables, and parts of the ground floor. When it passed into the hands of the Prokopiou family, restoration began immediately, with the aim of reviving the entire property along with its orchard.

Designed as a quintessential summer residence, its architecture clearly reflects a priority on comfort and well-being over agricultural productivity. Yet, as the architect notes, “The heart of the estate is the manganopigado; without it, nothing here would exist. The irrigation still works the same way, though today it is powered by a motor instead of animals.”

He explains that the guiding principle throughout the project was respect for the authentic character of Kampos, so the people involved adapted to the needs of the house rather than the other way around. “Where necessary, we intervened decisively; elsewhere, we left things untouched, such as the floors or the painted ceilings. The plaster is original, the roof repaired, and the electrical installations modern but hidden, so as not to alter the building’s character.”

Anneza Klouva cultivates organic citrus fruits.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The Perleas Guesthouse, housed in a 17th-century mansion that took its present form in 1983.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The private residence of the Prokopiou family is open to the public three times every summer. Equally famous is the Argentikon, founded by one of the most historic families of Kampos. Spanning 28 acres, its gardens seem endless, with broad walkways intended for the owners and narrow ones reserved for the staff. The two were not to cross paths, even by accident. The grounds are rich with history: crests and monuments, cisterns and fountains, bougainvillea, hammams, pyrgousika xysta (decorative carvings typical of Chios), countless shaded resting spots, and several buildings that housed the Christakis family guesthouse until 2020.

Since last year, the estate has been under the ownership of the Tomazos family, serving both as a private summer home and an event venue. The guesthouse is expected to reopen, according to Giorgos Giannoumis, the estate’s caretaker, who guided us through the grounds with obvious admiration and affection, qualities shared by many caretakers and anestates, whose devotion to the land is deeply felt.

Only a handful of Kampos estates remain in the hands of local owners today. The rising cost of upkeep and high property taxes have forced many to sell, often to wealthy entrepreneurs – a modern continuation of Kampos’s historical connection to maritime wealth and influence.

One of the few exceptions is Dimitra Apessou, who has created a vibrant, self-sufficient world on her estate. Here, she grows vegetables and raises animals, maintains a traditional home, a working orchard, and the charming Astrakia Guesthouse. Offering us a glass of fragrant homemade mandarinade – the same drink she serves to her guests at breakfast – she speaks fondly of her family’s roots: her parents, born in Egypt; her grandfather, who purchased the estate in 1920; and the estate’s old tower, which survived the Genoese era only to collapse in the great earthquake.

The Antouaniko received a Europa Nostra award for its exemplary restoration.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Stories seem to pour effortlessly from Margarita Martaki, president of the Progressive Association of Kampos (F.O.K.). She tells us that the mandarin harvest had to be completed before the sound of the toubi – the drum that signals the start of Christmas carols – echoed through the fields. She conjures scenes of dreamy evening gatherings and hunting excursions across the orchards, her voice weaving a living history. We could listen to her for hours.

She recalls the names of old estate owners – names that still hold weight among locals, even as the properties have changed hands many times – as well as the names of anestates. She speaks of olive trees planted around the orchards to shield them from sea winds and salt, of stone pines whose roots now crack the pebble-paved courtyards, and of the small gates that separate home from grove, a quiet threshold between domestic life and the agricultural world.

To experience Kampos, one needs only curiosity; the willingness to look, to listen, to feel: the birdsong that wakes you at dawn; the croak of frogs in the distance; the musical cadence of the local dialect, with its soft irony and warmth.

View of the charming Argentiko mansion, which is expected to reopen as a guesthouse.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Dimitra Apessou, owner of the Astrakia Guesthouse.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Today, visitors are slowly beginning to discover Kampos. Guided by F.O.K. or Chios Paths, small groups explore historic buildings and hidden gardens. They admire bell towers that are artworks in themselves and visit mansions like Riziko, which now host cultural events, while others, sadly, crumble from neglect.

Local women gather at the F.O.K. center to craft traditional handiwork, later displayed with pride during summer exhibitions. The village school doubles as a square, welcoming the children of migrant families for play and community activities. Lilies bloom in stone cisterns. The air is perfumed with honeysuckle, jasmine, tsikoudia (the native pistachio tree), and linden. A landscape not just seen but sensed; a living tapestry woven from scent, sound, light, and memory, treasured by locals and visitors alike.

As Mr. Xydas notes, “We are all visitors here, except for the trunks of the trees. Some are 400 years old; I remember them looking exactly the same when I was a child. I used to gaze at them in awe, and my father would say to me: ‘Did you hear what the estate said, little Vaggelis? It said, Welcome, visitor.’”

From kafeneia serving souma and meze...

On the Cycladic island of Tinos,...

With its beautiful olive groves, emerald...

Charming architecture, unique beaches, rich history,...