Where conservation meets tradition, a village adapts to living alongside Greece’s returning wild predators.

We arrived in Nymfaio late at night, just in time to cross paths with Thomas, a young male bear who hurried across the empty road, startled by our headlights. Found orphaned in a Florina village in 2022, he had been taken in and raised by local wildlife NGO Arcturos. After months of rehabilitation, he was released back into the wild. Every now and then he reappears in the surrounding area, as if to remind visitors that the Vitsi region remains one of Greece’s most vital brown-bear habitats.

I first visited Arcturos seventeen years ago, when just ten bears lived behind the sanctuary’s fences, all rescued from captivity. Among them was Giorgakis, one of the former “dancing bears” confiscated at the time. Seeing him again now – safe, serene, and nearly blind with age – in the 50-acre Bear Sanctuary was profoundly moving. He now shares this expansive forested enclosure with twenty other bears, each with a name, a history, and a personality of its own. Some were taken from circuses or private owners; others arrived orphaned, like Thomas.

Tracks of a wild wolf on Mount Vitsi.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Bear at the Arcturos Sanctuary.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Arcturos itself began as an idea in 1992, when Yannis Boutaris – then a winemaker and conservation advocate, later the mayor of Thessaloniki – saw a dancing bear at a circus he was attending with his son. The sight, combined with his deep love of nature, spurred him to act. At the same time, he envisioned the initiative as a way to support the future revival of Nymfaio, which he and community president Nikos Mertzos were working to restore during that decade.

Much has changed in Greece in the twenty-three years since those early days both for bears and for wolves, the latter sheltered at Arcturos’ Wolf Sanctuary in Agrapidies. In the early 1990s, both species hovered on the brink of extinction. Dancing bears could still be seen despite protective legislation dating back to 1965, and wolves had been hunted more relentlessly than any other animal. Back then, only about 130 bears were thought to survive in Greece, and wolves had all but disappeared. Today, populations have rebounded: roughly 1,000 wolves and about 900 bears now roam the country, according to biologist and Arcturos director Alexandros Karamanlidis.

This remarkable recovery stems from the early work of Arcturos and later that of Callisto, another environmental NGO founded a decade afterward, as well as from systematic research by biologists and Greece’s gradual alignment with European wildlife legislation. “Public sentiment mattered enormously,” says Panos Stefanou, Arcturos’ communications officer. “Greek society was ready for change; people never truly accepted dancing bears – something deep down resisted it. And awareness-raising among livestock breeders, farmers, and local communities played a decisive role. Arcturos has always invested tremendous energy there.”

Wolf inside the Sanctuary. During your visit, it’s possible you may not see any animals at all.

© Dimitris Tosidis

The lynx has been absent from Greece for many years. Rumors suggest sightings near the borders, hinting its return may be only a matter of time.

© Dimitris Tosidis

A Shared Landscape

We follow him into the dense forests of historic Mount Vitsi, a sweeping expanse of beech and oak that mirrors the wider biodiversity of the Pindus range. Today, the bear population extends as far south as Evrytania, while wolves have reappeared all the way down to Attica and even the Peloponnese. With us are local guide Giorgos Mostakis and biologist Lambros Krampokoukis, Arcturos’ research coordinator and head of the organization’s rapid-response team.

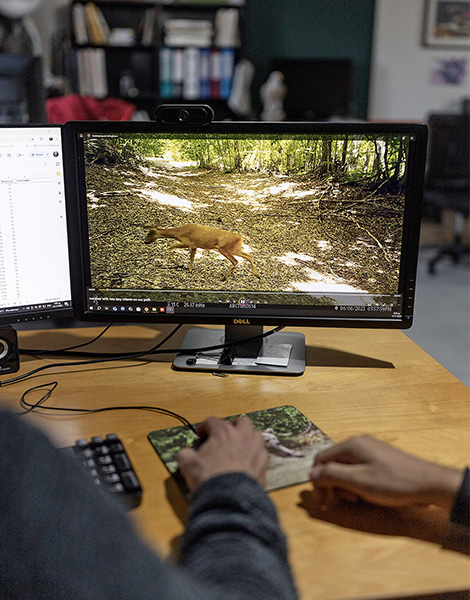

Krampokoukis leads Arcturos’ long-term biodiversity monitoring program, designed to track wildlife activity and assess the impact of human presence, including hunters, loggers, hikers, and the researchers themselves. Forty-one camera traps are positioned across Mount Vitsi, supported by the collection of scat, hair, and other biological samples.

Each month, he gathers the field data and uploads it to the organization’s central database before the scientific work begins. The genetic material is sent to a specialized laboratory in Canada for analysis and identification; the results have formed the basis of the National Brown Bear Registry. “With 25,000 individual recordings, we can now answer thousands of questions,” he explains, noting that much of the material is used by the organization’s student researchers. Proud of the program and Arcturos’ extensive volunteer network, the team hosts students from universities around the world, immersing them in every aspect of fieldwork, right down to visits to mountain livestock farms, where tensions with herders are not uncommon.

We follow him to one of the camera traps. In just three weeks, it has captured 75 recordings of martens, foxes, wild boar, wildcats, and five different bears, some of them with cubs. Watching them navigate the same territory as a large male – an unusual overlap, since mothers typically avoid males to protect their young – one conclusion becomes clear: the animals are being squeezed for space.

The Nikeios School, Nymfaio’s most iconic building, houses the Brown Bear Information Center.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Coexistence Is Possible

It was one of the most beautiful sights I’ve ever witnessed: three graceful lynxes playing like puppies right in front of us, while a little further away two white Arctic wolves paced with quiet majesty along the fence of the Wolf Sanctuary. Here, twelve wolves share their home with eight jackals, five roe deer, five lynxes, one red deer, and thirty Greek sheepdogs, a breed that Arcturos raises and provides to livestock farmers. These dogs are essentially the bridge between humans and wildlife, guarding herds and deterring bears and wolves.

Yet sightings of wild animals within villages are becoming increasingly common, triggering concern. “I often hear older locals saying that bears were plentiful in the past too, but they never came into the villages,” notes Karamanlidis. “But back then there were no highways like the Egnatia Odos, no uncontrolled placement of wind farms or road construction, and far fewer wildfires disrupting the ecosystem. The mountains are no longer theirs alone; they’re being squeezed, so they inevitably move into inhabited areas.” He adds: “These pressures are among the greatest threats they face. Greece has made remarkable progress in protecting both species, but their future is far from secure. There were always bears and wolves here, yet we still drove them to the brink of extinction once – it could happen again.”

Across the Pindus, many villages have been abandoned, becoming part of the forest and offering wildlife little indication that humans once lived there. Lambros Krampokoukis spent weeks visiting nearby fields daily to drive away Martha, a young female bear recently released back into the wild who was searching for easy food amidst the crops. She quickly learned and retreated into the mountains. “You can’t leave garbage outside and expect a wolf to choose to hunt instead, nor can you leave fruit hanging in your courtyard trees and assume a bear won’t come looking,” he explains. Even electric fencing requires proper installation: most people place the lowest wire too high, allowing bears to dig beneath it; others fail to clear surrounding vegetation, which causes grounding when branches touch the wire.

Lethal control or forced removal, researchers insist, is not the answer. Coexistence is possible – if we choose it. “In Greece, the official response mechanism is unfortunately ineffective. In most incidents, it ends up being Arcturos and Callisto’s rapid-response teams who intervene,” says Stefanou. He and Mostakis then tell of countless bear encounters over the years, none of which ever put them in real danger. In the Florina region, Arcturos and the Municipality of Amyntaio have just published a Coexistence Guide for residents.

Krampokoukis dreams of a model like Canada’s. “There, even though bears are strictly protected, if one enters a garden the forestry authority is legally allowed to euthanize it. And yet people rarely call them – they don’t want the bear killed, so they rely on deterrents instead. Could we ever reach that point in Greece too?”

Biologist Lambros Krampokoukis spends his entire day out in the field.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Data are analyzed on the computer by biologists and students, leading to scientific publications.

© Dimitris Tosidis

9 Unique Experiences

1. Strolling Through Nymfaio

It’s no secret that Nymfaio is one of Greece’s most beautiful villages and that its revival is thanks to the efforts of Yannis Boutaris and community leader Nikos Mertzos. Restored mansions with painted or carved wooden ceilings, stone-paved lanes, handsome guesthouses, and a sweeping beech forest all around define the setting. See the engaging exhibition presented in the Arcturos Information Center, housed in the building of the Nikeios School. Wander through the village to take in the architecture and iconic tin-covered roofs, browse wine and local products at Dadalina’s (Tel. (+30) 23320.511.00), and stop for a coffee at Enterne (Tel. (+30) 23860.312.30). Don’t miss the post-Byzantine church of Aghios Nikolas or the Athina Heritage Mansion, officially designated as a work of art.

2. Hiking in the Forests

Hiking on Mount Vitsi is a thrilling experience, offering the chance to encounter wildlife in its natural habitat. If you’d prefer not to encounter animals, making a bit of noise helps keep them at a distance. Arcturos has opened six hiking trails based on the area’s old footpaths. The Pink Trail is already signposted, and Penny Turner’s guide 6 Antidotes to Technology, available from the NGO, describes each route in detail, along with the flora and fauna you may encounter.

Through the cameras, biologists can observe not only the variety and number of species, but also their behavior.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Canoeing on Lake Zazari.

© Dimitris Tosidis

3. Horseback Riding in Sklithro

Twenty Pindos horses roam free on Takis Voglidis’ 6.4-acre estate, offering memorable rides: from short forest routes around Sklithro to a multi-day expedition around the area’s four lakes, complete with camping. Tel. (+30) 23860.310.28; artemisoe.gr

4. Canoeing on Lake Zazari

Sixty minutes of absolute calm: birdsong, splashing fish, and the gentle dip of your paddle in the water are the only sounds around you. The Voglidis family of the Artemis Activity Center also offers guided activities such as hiking, cycling or mushroom foraging around the lake’s shores. Tel. (+30) 23860.310.28; artemisoe.gr

5. The Circuit of Lake Cheimaditida

Exploring the lake’s perimeter feels like stepping into an adventure story told in slow, scenic chapters: two livestock farmers with their herds, a handful of amateur fishermen who organize local fishing competitions, a few professionals with their flat-bottomed boats and nets, a recently arrived herd of water buffalo, reed beds alive with birds, and a dirt road circling the lake past the old stone winter shelters that give Cheimaditida its name.

Horseback riding with Takis Voglidis in Sklihtro.

© Dimitris Tosidis

6. Wine Tasting with Depth

There’s something moving about discovering the stories behind the labels you drink: Samaropetra with its stunning views; the legendary Paranga; how Kali Riza got its name; and which grape variety was the favorite of the visionary and pioneering Yannis Boutaris, who passed away last year after seeing the company’s new winery in Amyntaio completed.

The region is deeply connected to Xinomavro and the Kir-Yianni winery, which is open to visitors. You’ll tour the vineyards and barrel hall, showcasing a remarkable range of aging vessels: oak barrels, clay amphorae, concrete “eggs,” and glass spheres. Tastings take place in a stunning room overlooking Lake Vegoritida. In the coming months, as part of the winery’s environmentally conscious philosophy and its mission to link wine with local culture, visitors will also be offered information on vineyard biodiversity, walking and cycling routes, and even birdwatching via cameras placed at feeding stations in collaboration with the Hellenic Ornithological Society.

Kir-Yianni Estate, Amyntaio. Tel. (+30) 23860.611.85; kiryianni.gr – Reservation required

7. Makalo Meatballs at Kontosoros

Makalo – a traditional Florina dish of beef meatballs served in a garlicky flour-based sauce – originated as a humble recipe made from whatever households had on hand. Nikos Kontosoros and Petroula Seltsa introduced it to their menu in 1989, when they opened the renowned Kontosoros restaurant in Xyno Nero, elevating local gastronomy and putting the wider region on the culinary map.

Although Nikos Kontosoros has passed away, his family continues the legacy with the same dedication to local produce and traditional recipes. All cheeses, meats, vegetables, wines are sourced from local producers. The service is warm and the dishes are refined yet deeply comforting. Tel. (+30) 23860.812.56

In the cellar of Kir-Yianni.

© Dimitris Tosidis

8. Water with a Name

It’s hard to believe until you taste it: Xynó Neró is naturally sour, flowing freely from springs in the village of the same name. Naturally carbonated, it is enhanced with a touch of extra CO₂ during bottling by the local municipal company. Internationally recognized for its quality, it’s served in every café and restaurant in the region, and the locals drink it with devotion.

9. The Hidden Gems

While Nymfaio may steal the spotlight, the surrounding villages are well worth exploring. Enjoy the Balkan atmosphere of Lechovo, reached by a beautiful, forested route; wander through Sklithro, with its preserved old mansions; stop for coffee and dessert at Vinylio (Tel. (+30) 23860.313.95) and for a meal at the famed Thomas (Tel. (+30) 23860.312.06). Continue to Asprogeia for superb homemade meze at To Proedrikon, a rustic village cafe-taverna known for its homemade meze (Tel. (+30) 694.633.2787).