Five Mountain Escapes for a Magical November

Discover five mountain destinations where crisp...

The sun illuminates the Attica basin, stretching out below Korakovouni.

© Perikles Merakos

Two young motorcyclists roar past, accelerating before vanishing behind a thicket of pines. Their shouts echo briefly, the drone of exhaust pipes cutting through the winter stillness. We are on Mount Ymittos, at an elevation of 525 meters, about to knock on the door of the Asteriou Monastery, one of nine monastic sites that, as Father Alexios later explains, spiritually “encircle the kleinon asty,” the illustrious city of Athens. Father Alexios arrived here in 2013, when the monastery was abandoned and bats had taken up residence inside. Today, he and two other monks conduct daily services. “Ymittos is the Mount Athos of Athens,” he says, inviting us inside.

Resting at Korakovouni.

© Perikles Merakos

Visitors who arrive early can attend the liturgy, but worshippers are only one group drawn to this secluded corner of Attica. Every day, Ymittos attracts a wide cross-section of Athenians: families on picnics, school groups walking along the trails with their teachers, runners testing themselves on uneven terrain, and Gen Z mountain bikers who treat the slopes as an informal downhill course. Others use the forest as a setting for yoga and meditation. “This is our therapy,” two young men told us earlier as they emerged from a trail near the monastery, helmets on and bikes ready for the descent. In this way, Ymittos functions as a microcosm of the Mediterranean mountain landscape; a place where different forms of escape coexist within a compact space.

What brought us here, however, was something more universal. Accompanied by Giannis Frydakis, head of Trekking Hellas Athens, and mountain guides Stamatis Sotirchos and Giorgos Karvelas, we followed a network of lesser-known trails in search of what unites nearly everyone we encountered along the way: a breath of fresh air.

The strawberry tree fruit – wild, juicy, straight from the forest.

© Perikles Merakos

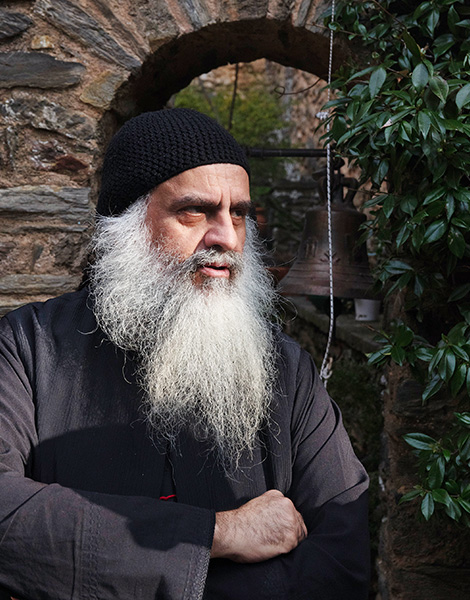

Father Alexios at the Monastery of Asteriou.

© Perikles Merakos

“The church was built by Saint Luke of Steiris, and the four ancient columns upon which it stands indicate that it was raised over the ruins of the school of the philosopher Diodorus,” Father Alexios explains inside the monastery. He points out a series of 18th-century engravings crafted in Jerusalem. As he speaks, two dogs wander in from the garden and settle nearby, quietly observing the visitors.

“Beneath the church floor lies a collapsed underground passage that once connected the monastery to Kaisariani Monastery and, according to tradition, extended as far as the Acropolis. The complex also featured a three-story defensive tower above the refectory and once housed a ‘secret school.’ From the tower, monks could watch for Ottoman forces and hide local children to protect them from forced conversion,” Father Alexios says. Until 1753, the monastery answered directly to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In 1833, a decree by King Otto dissolved it as an independent monastery due to its small monastic population, merging it with the Petraki Monastery in central Athens.

© Perikles Merakos

By 1897, the monastery had fallen into complete disrepair and was eventually burned. A renovation in the 1930s restored the monastery as a single-story structure. In the late 1950s, Queen Frederica assumed control of the complex, converting it into a summer residence and displacing the three nuns who lived there at the time.

In the past, travelers passing through the monastery’s gates could expect shelter, food, and spiritual guidance. Mount Ymittos was once rich in wildlife, particularly hares, and after the army constructed a road in 1959, the area became a frequent destination for royal hunting expeditions. Today, prayer remains central to the monastery’s life, but Father Alexios also leads visitors to the beehives at the back of the grounds. Beekeeping, he explains, was the monastery’s traditional labor, or ergocheiro. Hymettian honey was long considered among the finest in Greece. “We try to revive this work,” he says. “It connects us to the fathers who worked this land centuries ago.”

Stacked stones form a “koukos” (an improvised trail marker).

© Perikles Merakos

A pleasant break at 728 metres, on the summit of Korakovouni hill.

© Perikles Merakos

Early in the morning, Giorgos stops to point out a puffball mushroom (lycoperdon). “It takes just a single raindrop to release a cloud of spores,” he explains. When he touches it, a small burst of powder drifts into the air. Nearby, several ant nests – six or seven clustered together – form what he describes as a small citadel. A runner passes without noticing the activity at ground level, nodding briefly as he moves downhill. “The mountain has its laws, written and unwritten,” Stamatis says. One of them is simple: greeting fellow hikers. Encounters here are brief but courteous, shaped by a shared presence on the trail.

Before long, the Tower of Anthousa, also known as the Koula of Ymittos, comes into view. Known by its Turkish name, it has stood in ruins since 1722. Although little documentation survives, its architecture suggests an Ottoman origin rather than Byzantine or Frankish. According to the guides, it was likely one of many koulades built across Greece until the 18th century, serving as watchtowers overseeing estates (chifliks), residences for local aghas, or military outposts.

© Perikles Merakos

From the tower, the trail leads toward the OTE Saddle, named for a former telecommunications relay station. The terrain shifts constantly, with short ascents and descents and the occasional fallen pine blocking the way. Giorgos pauses beside a decaying trunk. Trees, he explains, endure rain, wind, snow, and disease; when stress coincides with weakness, they fall and slowly return to the soil. The process is natural, but he notes that prolonged drought – intensified by climate change – is taking a visible toll. Warmer winters and reduced rainfall allow pests to persist longer, placing pressure on species such as the Greek fir.

Along the path, Jerusalem sage (apsaka) grows beside wild sage, one known for triggering allergies, the other prized as a culinary herb. Nearby, wild thyme releases a sharp scent that briefly cuts through the winter air. Giannis notes that Mount Ymittos is home to more than 40 species of wild orchid, giving it one of the highest orchid densities relative to its size. What draws his attention here, however, is a wild asparagus shoot pushing through the soil, an out-of-season reminder of spring.

Rising to 1,026 meters, Ymittos is the third-highest mountain in the Attica Basin. To the west lies the dense sprawl of Athens; to the east, open plains stretching toward the airport. To the north, the outlines of Mount Penteli and Mount Parnitha are clearly visible. “On a clear day,” Giorgos says, “you can see as far as the snow-covered peaks of Mount Parnassus.”

The Tower of Anthousa, also known as Koula of Ymittos.

© Perikles Merakos

Downhill enthusiasts hurtle downhill on their bikes.

© Perikles Merakos

Weather is often the deciding factor in a hiker’s experience, capable of altering every aspect of a mountain’s character. “The mountain offers something different at every moment,” Giorgos says. “One minute later, you may be looking at an entirely different world.” When he leads groups, he adds, the landscape has a way of leveling distinctions. People from varied backgrounds respond in much the same way – often with a smile, sometimes with visible emotion. “They say, ‘I can’t believe what I’ve been missing all this time.’”

He recalls a hike with a group of schoolchildren and their teacher. As the children stumbled along the uneven trail, the teacher encouraged them rather than intervening. “Let them learn how to walk,” she said.

At the OTE Saddle, we choose our route. Rather than heading immediately to “The Ridge” – a viewpoint offering sweeping views from the port of Piraeus to the Mesogeia plains and the airport – we turn first toward Korakovouni, or Raven’s Mountain. Just before leaving the forest canopy, we come across a koukos, a cairn made of carefully stacked stones. Before trails were marked, Christos explains, such structures served as navigation aids, their name linked to Greece’s earliest mountaineering associations. Giorgos has the symbol tattooed on his arm.

Enjoying the scent of wild thyme.

© Perikles Merakos

Sage leaves seen up close.

© Perikles Merakos

Near the summit, young pines spread across the slope. Giorgos points out their low growth. A fire in 2008 burned this section of the mountain, but pine trees, he explains, are uniquely adapted to recover. Some cones survive fires by bursting open rather than burning, releasing their seeds within days. Others lie dormant in the soil – sometimes for decades – emerging in the first year after a fire. A damaged pine can reproduce within 15 years, a process he describes as both efficient and resilient.

A stone marker signals the 728-meter summit. Two young hikers wave as we arrive; they began their trek at the Monastery of Aghios Ioannis and plan to continue toward Terpsithea, a route that can take six hours or more. Nearby, names etched in pencil and pen mark the stones. “The only thing you should leave behind on a mountain is your footprints,” Giorgos says.

The group falls quiet. By midday, the sun illuminates the Mesogeia plains on one side and the Attica Basin on the other. On clear nights, city lights are visible from this point, but the shifting winter light filtering through the clouds is enough. It is a moment shaped by effort and timing, one that will not be repeated in quite the same way. As Giorgos notes, the mountain’s defining quality is its ability to change with every visit.

The hike began at the Dimitris Karamolegos Fire Lookout Station in Kaisariani, passing the Tower of Anthousa, ascending Korakovouni, reaching the Ymittos ridge, and descending to the Asteriou Monastery. The route covers 10.5 kilometers (approximately 6.5 miles) and is rated moderate in difficulty. Total hiking time is approximately five hours, with a maximum elevation of 834 meters.

Trekking Hellas Athens organizes guided hikes through Athens’ historic neighborhoods and on Mount Ymittos. For more information, visit trekking.gr

Tel. (+30) 210.923.8661

Discover five mountain destinations where crisp...

A major restoration project is bringing...

A monument of memory and music,...

Since 1928, this family-run wine taverna...