Restoring Sacred Power to the Parthenon

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

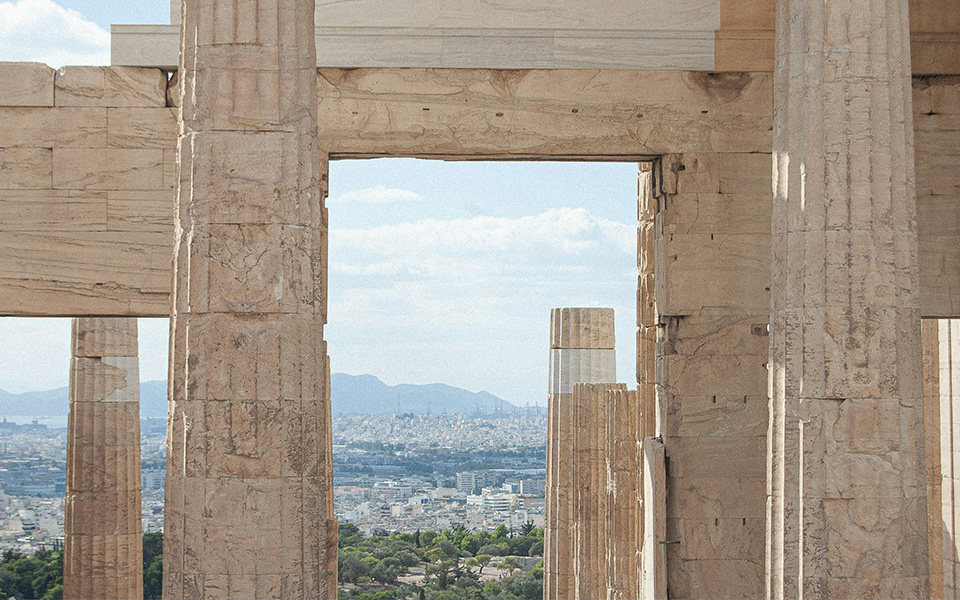

© Shutterstock

In 1801, the Scottish aristocrat Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, more commonly known as Lord Elgin, recruited a team of artists, led by the Italian painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri, to remove sculptures from the Parthenon. In his capacity as British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which ruled Greece at the time, Elgin and his team spent two years hammering, chopping, sawing, chiseling and carving out massive chunks of the temple. These ancient Athenian monuments, which rank among the greatest artifacts of world civilization, were designed by Phidias between 445 and 432 BC as part of a grand project commissioned by Pericles.

This treasure trove of antiquities weighing 100 tons was then packed into roughly 200 crates, loaded onto wagons and transported to the port of Piraeus for passage to Britain. Elgin’s haul included 56 of the 97 surviving blocks of the frieze (originally 160 meters long), 15 out of 62 metopes and 19 of the preserved fragmentary sculpted figures of the pediments, all of which have now spent over two centuries on display at the British Museum in London.

Since its independence from the Ottomans in the 1820s, Greece has, through a succession of governments, petitioned Britain for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures. During her time as Minister of Culture between 1981 and 1989, famed actress Melina Mercouri reignited the country’s bid to repatriate the artifacts. In 1984, she made a formal request for the return of the sculptures via a UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee (ICPRCP), a body established to restore cultural property to their countries of origin. Britain summarily dismissed the claim.

Two horsemen galloping, from the West Frieze. An examination of the folds of the second rider’s tunic has revealed traces of green paint.

© ACROPOLIS MUSEUM PHOTO: SOCRATIS MAVROMMATIS

In recent years, Greece has taken up the cause of restitution with renewed vigor. Ever since Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis came to power in 2019, he has made it a priority to compel Britain to abandon its policy of inertia and serial “non-denial” denials and restore the sculptures to their rightful place in Athens.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Elgin pulled off the greatest act of cultural misappropriation in history, and it’s high time that Greece forces Britain to confess to this act and return the stolen goods.

But after three years of haphazard negotiations between Greece and the UK, talks between the two nations have broken down, with no resolution in sight. During a Greek tourism conference organized by Kathimerini in November, in conjunction with the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre, Mitsotakis confirmed that progress on returning the sculptures has stalled.

There have, of course, been unconfirmed reports of a possible face-saving plea deal whereby the sculptures would be “loaned” to Greece by the British Museum in exchange for a replacement set of Greek antiquities to be displayed in London.

Of course, this would be tantamount to accepting a bilateral “plea deal” under which Greece effectively legitimizes Britain’s ownership of the sculptures in order to have them repatriated and presumably allowed to remain in the Acropolis Museum in perpetuity. But such an arrangement implies that Greece would be willing to pay a ransom for its own ancestral patrimony by swapping a rotating series of new Greek antiquity collections as compensation for its own looted treasures.

In the course of his remarks at the tourism conference, Mitsotakis did indicate that it may be necessary to think out of the box in order to achieve the goal of reunifying the treasures.

The prime minister did not, however, state at any point in his remarks that Greece would in any way acknowledge or accept that Britain “owns” the sculptures, which sources on both sides suggest is the principal stumbling block in the negotiations.

Crime scene? A watercolor from the “In Search of Greece” exhibition catalogue featuring works by Edward Dodwell and Simone Pomardi.

© COLLECTION OF THE PACKARD HUMANITIES INSTITUTE, 2013

The current impasse in negotiations hinges on the controversial British Museum Act of 1963, which prohibits the permanent disposal of any objects that are part of its collection. This self-serving legislation was a thinly veiled means of preventing more enlightened British governments or trustees of the museum from doing the right thing and unconditionally returning the sculptures. When asked to comment for this story, a British Museum spokesperson issued the following statement on behalf of its director, Dr Nicholas Cullinan.

“Discussions with Greece about a Parthenon Partnership are ongoing and constructive. We believe that this kind of long-term partnership would strike the right balance between sharing our greatest objects with audiences around the world and maintaining the integrity of the incredible collection we hold at the museum,” read the reply, which was received before Mitsotakis’ speech.

The use of the word “our” in reference to “greatest objects” implies that the British Museum still considers the Parthenon Sculptures to be British property. Cullinan’s proposal for a “partnership” merely suggests that its greatest objects (i.e., the Parthenon artifacts) should be shared with “the world” in general – not Greece specifically – in order “to maintain the integrity of its existing collection.”

This latter statement is as misleading as it is confused: the only way to ensure the “integrity of [the] collection” is to return the sculptures to their original home in Athens, where the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum will serve as the permanent home for a newly reunited frieze and the rest of the Parthenon Sculptures.

Sculptural elements in the Parthenon Gallery, on the third floor of the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum in Athens.

© Wassilis Aswestopoulos / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

Cullinan’s advocacy for a “partnership” would maintain the fiction that Britain – via its flagship museum – is the legitimate owner of the sculptures, as demonstrated in his remarks to the leading Spanish daily El País this August: “We can’t give things away, but there is absolutely nothing preventing us from sharing the collection .. I think you have to focus on what’s possible, rather than arguing over what you could try and make happen.”

The British Museum director’s attitude is borne out by an earlier, November 2024, interview with London’s Financial Times. Said Cullinan: “I’d like to talk more about a partnership rather than debating ownership.” In effect, the 1963 Museum Act affords Cullinan diplomatic cover so that he can reject any possibility of outright repatriation. Given that British Prime Minister Keir Starmer has indicated his government does not intend to repeal the 1963 act, the Greek government is left with little room to maneuver.

The British Museum’s insistence on a “loan” agreement is a diplomatic workaround that bypasses the 1963 law, whereby Greece would retain its “borrowed” national treasures repatriated in perpetuity while tacitly or otherwise acknowledging that Britain is still their owner. This would plainly put the Mitsotakis administration in a very difficult position.

However, sources inside the Mitsotakis administration have indicated that Greece is not about to give ground on the question of ownership, despite Culture Minister Lini Mendoni’s offer to provide Britain with “rotating exhibitions of important antiquities [at the British Museum] that would fill the void” in exchange for restitution.

Marble relief from the North Frieze of the Parthenon, showing the procession of the Panathenaic festival, the commemoration of the birthday of the goddess Athena.

© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

In the meantime, the British Museum caused a diplomatic row in October by staging a glittering fundraising gala – the first annual “Pink Ball” – that attracted Mick Jagger, Jerry Hall, Sacha Baron Cohen, Kristin Scott Thomas, Miuccia Prada, Manolo Blahnik and scores of other celebrities, VIPs and billionaires, who each paid £2,000 to attend an event that raised €2.7 million for the museum’s renovation campaign.

The illustrious guests were seated and served dinner under the gaze of the Parthenon Sculptures housed inside the museum’s Duveen Gallery and which remain one of London’s greatest tourist attractions. The optics of staging this event a mere few meters away from Greece’s cultural heritage was not lost on Culture Minister Mendoni, who responded with dignified scorn.

“The safety, integrity and ethics of the [Parthenon] monuments should be the main concern of the British Museum … [but] once again it is exhibiting provocative indifference,” she said.

The minister’s remarks were echoed by the speaker of the Greek Parliament, Nikitas Kaklamanis, who mocked the British Museum for deciding to “cover Greek culture in the [pink] shade of Barbie,” while also decrying the crass exploitation of the sculptures as a “tourist attraction.”

“At a time when the Parthenon Sculptures, born in Athens 2,500 years ago, are patiently awaiting their return to their homeland … the British Museum lays out provocative, lavish tables in the Duveen Gallery with our sculptures as a backdrop and cynical means of raising money for its own benefit,” he said.

The fundraiser not only dampened the mood in Athens but reinforced the notion that Cullinan’s talk of a “Parthenon Partnership” is a somewhat misleading formulation for what many view as cultural appropriation.

The Parthenon Marbles on display at the British Museum.

© Shutterstock

This is equivalent to diplomatic doublespeak and is the kind of smokescreen that German and Austrian museums have systematically employed since the end of WWII to obstruct the repatriation of artworks that Nazi officers and Nazi-connected gallerists forcibly appropriated from prominent Jewish families.

The British Museum’s ambiguous offer – “sharing our greatest objects with audiences around the world” – repeats the historic myth that the Parthenon Sculptures belong to Britain. This is the same attitude taken by German, Austrian and American officials with respect to restitution of stolen artworks.

It remains difficult to comprehend how any nation would continue to endorse an arrangement viewed by many as state-sanctioned misappropriation. But this is precisely the implications of the “loan” and “partnership” schemes that obscure key facts in the service of plainly revisionist history.

The British stance is comparable to that of Germany and Austria, which have grudgingly returned less than 10 percent of stolen Jewish artworks. The most notorious example of this was the sensational decades-long legal campaign by Maria Altmann, a Jewish refugee living in the US, to force an Austrian museum to return six paintings belonging to her, most notably Gustav Klimt’s 1907 portrait of her aunt, Adele Bloch-Bauer, entitled “Woman in Gold.” Altmann’s legal battle for restitution was dramatized in the 2015 film “Woman in Gold,” starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. (Bloch-Bauer’s diamond necklace was also seized by Hermann Goering, who gave it to his wife.)

After the war, the paintings turned up in Austria’s federal art museum, the Galerie Belvedere. The Austrian government said the paintings had been willed to the institution, a claim that Altmann and her legal team proved was fraudulent. Ultimately, an independent tribunal in Austria agreed that the paintings belonged to Altmann and ordered them to be returned to her she subsequently sold “Woman in Gold” to American billionaire Ronald Lauder for $135 million, and he put it on display at his museum in New York City.

The case for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures to Greece is infinitely superior to the case for the restitution of the Klimt painting and many other similar cases of looted Jewish art. The Parthenon artefacts belong not to an individual or a family, but to all of humanity. Furthermore, the sculptures are part of the heritage of ancient Greek civilization itself, one of the most important eras in world history, and a symbol of democracy itself.

So how can it be that, long after most legal experts and international bodies have accepted the principle of restitution of national treasures to their homeland, the British Museum is still holding onto misappropriated property?

© Shutterstock

The British Museum and the UK government continue to cling to the fallacy that Lord Elgin’s removal of the sculptures was legally authorized by the Ottoman Empire. According to this official narrative – rooted in myth rather than fact – Elgin allegedly obtained a firman (an authorizing document) from Ottoman Sultan Selim III that gave him permission to remove the “marbles,” which he later installed at his estate as his own private museum exhibit that drew scores of curious visitors.

This original, all-powerful Ottoman firman has never been found; belief in its existence relies entirely on a translation written in Italian, most likely composed by Elgin’s overseer Lusieri. According to a landmark 1967 study by British historian William St Clair titled “Lord Elgin and the Marbles,” the terms of the firman did not in fact allow for the removal and export of the sculptures.

St Clair found that a clause – again, one that is referred to in the dubious Italian translation, unsigned and without an official seal – authorizing Elgin to “take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures thereon” – most likely referred to items found in the excavations conducted on the site, not the magnificent artworks adorning the Parthenon.

Painting of the ruins of the Parthenon and the Ottoman mosque built after 1715, by Pierre Peytier (early 1830s).

Greek doubts as to the authenticity or existence of the firman have now been substantiated by an unlikely ally, the Turkish government. Last June, Turkey for the first time categorically rejected the British version of events which regards the firman as a form of holy scripture that allowed Elgin to execute his disfiguring of the Parthenon.

According to Zeynep Boz, the Turkish culture ministry’s senior anti-smuggling official, there is nothing in her country’s archives to support the existence of a valid firman regarding the sculptures. This once and for all demolishes the centuries-old fictitious British claim that Elgin’s removal of the sculptures had legal justification.

“Turkey is the country that would have the archived document pertaining to things that were sold legally at that time. Historians have for years searched the Ottoman archives and have not been able to find a firman proving that the sale was legal, as it is being claimed,” Boz told the Associated Press.

In a subsequent interview with Greek state broadcaster ERT, Boz stated that the only semblance of an authorizing document was an edict written in Italian, but it crucially lacked the state seal and signature of the sultan, which would have given the document official status or otherwise indicated that it had been issued by any official on behalf of the Ottoman government.

In an interview with the UK’s Guardian, Elena Korka, the Greek culture ministry’s director general of antiquities, declared that the Turkish official had undermined the entire British case for blocking repatriation: “It is hugely important that a very senior Turkish official who has all the archives … at her disposal has declared that nothing has been found and there is no [authorizing] document. They looked and couldn’t find it – that’s because it never existed.”

A further debunking of the British claim that Elgin legally acquired the marbles are the circumstances under which the British Parliament approved their purchase in 1816 and thereby sanctioned the act. The sale came about when the profligate Lord Elgin, a direct descendant of the Scottish King Robert the Bruce, found himself on the verge of bankruptcy and urgently needed the British government to purchase his booty.

The case of the Parthenon Sculptures became well known in Britain, particularly after Lord Byron, the great Romantic poet, began vilifying Elgin in public. Byron categorized Elgin as a vain, self-important “dull spoiler” and wrote a satirical poem, “The Curse of Minerva,” that described the Scottish nobleman as “loathed in life, nor pardoned in the dust.”

Elgin’s attempt to sell the sculptures thus constituted a potential public relations disaster for the government. In the debate on the petition to set up a British parliamentary select committee to consider the authority by which Lord Elgin’s collection was acquired, disquiet was expressed about the way he had obtained the sculptures and whether he had abused his status as ambassador. In the end, Parliament approved the purchase by a vote of 82 to 30.

Ever since, Britain has resorted to the “safekeeping” argument to justify its refusal to return the sculptures by citing Greece’s lack of secure borders and political instability. Of course, even the most casual observer of history would note that Greece became independent in 1830 when it was officially recognized as a sovereign state with the signing of the London Protocol. But any present-day British references to Greece’s inability to keep the sculptures safe from subpar museum standards were rendered moot when the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum opened its doors in 2009.

There can be no doubt that this glittering venue is a fitting postmodern structure where the Parthenon Sculptures can finally be reunited, in contrast to the dilapidated, dismal and leaking British Museum that houses the marbles removed by Elgin. (The British press has regularly reported on how the museum’s Greek, Assyrian and Egyptian galleries have been plagued with water seepage and a lack of ventilation, requiring staff to deploy fans, space heaters and plastic tarpaulins to prevent damage.)

Half of the surviving Parthenon Marbles have been on display in the British Museum since 1817.

© Shutterstock

In 2008, Christopher Hitchens, arguably the leading British public intellectual of his time and one of the world’s most articulate political pundits, published “The Parthenon Marbles: The Case for Reunification.” This powerful book makes the strongest case yet for restitution. Hitchens explains that Greece is one of many nations subjected to cultural expropriation by imperialist powers.

The fact that so many ancient artifacts from Greece, Egypt, Syria, Africa and other nations have been redistributed to British, European and American museums is proof that colonizing or occupying powers have often used their military superiority to acquire the treasures of weaker states.

Hitchens argued that the Parthenon Sculptures were part of a temple that celebrated the Athenian city-state. He described Phidias’ friezes as “monuments to gods, warriors and mythical creatures,” while noting that the metopes depicted mythological battles – Athenians against Amazons and Centaurs – as allegories of the Greco-Persian Wars.

Interestingly, Hitchens also suggests that the construction of the Parthenon and the Acropolis were part of what he describes as a “Periclean Keynesian” pump-priming of the local Athenian economy.

“The city needed to recover from a long and ill-fought war against Persia and needed also to give full employment (and a morale boost) to the talents of its citizens. Over intense conservative opposition, in 450 BC Pericles pushed through the Athenian Assembly a stimulus package proposing a labor-intensive reconstruction of what had been lost or damaged in the Second Persian War.”

In his book, Hitchens scoffs at the outdated arguments concerning Greece’s institutional unfitness to properly preserve and enshrine the sculptures. In addition to a return of a fragment from Heidelberg University, a non-state institution, in 2006, states have also repatriated pieces. In 2022, the Italian government returned the Fagan fragment, which had been held at the Antonino Salinas Museum in Palermo; this was followed in 2023 by a return from the Vatican Museum. Yet the British Museum insists that displaying the misappropriated artifacts on its premises allows the world to “affirm the legacy of Ancient Greece.” So why can’t the Acropolis Museum now assume that role and put all the pieces back together in one place for the world to see?

Hitchens had no patience for such nonsense: “There are no Babylonians left, there are no Hittites, there are no Aztecs left; whereas the Greeks still speak a version of what you can read in the inscriptions [on the Parthenon] in Athens. There’s a continuity to the claim there, and that temple is still their national symbol, as it is of the European Union.”

The highly regarded Cretan journalist Kostas Papageorgiou, widely known for his TV documentaries on Greek history and culture, is no less a vociferous advocate for the return of the sculptures. Now living in Scotland, where he spent five years researching his latest book, a monumental biography of Robert the Bruce, Papageorgiou has done intensive research on Lord Elgin and the rough, chaotic manner in which his team of artists removed pieces of the Parthenon without regard to the damage this caused. “The Parthenon Sculptures are not merely works of art; they are monuments to Greek civilization and living symbols of Athenian democracy and the spirit of ancient Greece,” said Papageorgiou.

“Lord Elgin’s plundering of the Parthenon was a savage attack on our history and patrimony, and it is the kind of festering wound that still causes great pain for the Greek people, who cannot imagine why the British government can still support the terrible lie that the removal of the antiquities was legal and [that they] should be considered property of the British Museum.”

Papageorgiou wholeheartedly endorses the arguments advanced by Hitchens and also cites important revelations contained in the provocative new documentary “The Marbles” by British filmmaker David Wilkinson, which was released in early November to glowing reviews in the British press.

Wilkinson exposes not only Elgin’s arrogance but his rampant duplicity and thirst for fame and money. More importantly, Wilkinson draws attention to how many European museums are now embracing the policy of restitution.

Papageorgiou was particularly impressed by how the documentary recounts a remarkable conversation with an unnamed former trustee of the British Museum.

“When the British people learn the whole truth through your film, I doubt there will be many who will believe we have any right to keep [the sculptures],” said the unidentified source.

“The British government is becoming increasingly isolated internationally on this issue. The late Pope Francis returned the Parthenon Sculptures from the Vatican because he knew that keeping them was wrong. It’s time for us to do the same … I never thought I would say that … The [sculptures] will be returned. It’s just a matter of time.”

Wilkinson also interviewed the star of HBO series “Succession” and inveterate Scottish nationalist Brian Cox, who states that if the marbles had found their way to Edinburgh, and not London, “they would have gone back to Athens a long time ago.”

Finally, Papageorgiou makes a fervent appeal to the Greek government to intensify its efforts to bring the sculptures back home.

“Greece needs to mount a more visible campaign by bringing on board high-profile artists, academics and leading intellectuals to shape world opinion and force the British government to abandon its hardline stance. We need to convince Britain to accept the increasingly accepted principle of repatriating national treasures to their countries of origin and give Greece back the sculptures that are part of our collective identity,” he said.

The time for soft diplomacy is over, he argues, and the Greek government must now apply maximum pressure on Britain to recognize that retaining the sculptures is a morally and politically untenable position.

© Ferran Feixas/Unsplash

The prevailing public winds are now blowing in Greece’s direction. A 2025 Parthenon Project poll revealed that 56 percent of Britons believe the Parthenon Sculptures should be returned to Greece, and only 22 percent believe the UK should keep them.

Greece clearly occupies the moral high ground on the matter of unconditional repatriation of the sculptures. Greece is the legitimate custodian of its antiquities. Principles of morality, memory, honor and justice are intertwined with an inescapable need to demystify and demolish Britain’s colonialist rationalisations for withholding these precious fragments of Greek civilisation, and bring Britain into line with the many nations whose courts are recognizing that national treasures should be returned to their countries of origin and that museums are honor-bound to repatriate looted artifacts.

The Parthenon Sculptures rank among the most precious and best-known antiquities of ancient civilization. The master sculptor and builder Phidias paid a glorious tribute to the Greek gods who represented the spiritual symbols of the Athenian city-state. Greece must now redouble its efforts to see that the sculptures, symbols that still reverberate in Greek consciousness and are inseparable from its national identity, find their way back to Athens and repair a gaping hole in the Greek soul. These magnificent marbles are vital proof of a lost Hellenic civilization whose democratic principles and contributions to art and philosophy continue to exert a profound impact on the world.

Papageorgiou made an interesting discovery during his research into the Bruce clan, of whom Lord Elgin was a member. He recounted the story of how Robert the Bruce was struggling over whether to send his Scottish soldiers into battle against King Edward II’s vastly superior English army. In the end, the king of Scotland was convinced by a close advisor to take the risk. “Now is the day, and now is the hour,” he was told.

Robert the Bruce then used his mastery of battlefield tactics to lead his highly trained soldiers to a decisive victory over England in the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn, a pivotal moment that paved the way for the restoration of Scottish independence.

Greece is faced with the same challenge. The Parthenon must be made whole again as part of a broad national resurgence. Now is the day, and now is the hour.

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

A personal exploration of Koukaki and...

Tourists share the highs and lows...

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...