Agapi from Poland Finds Expression in the Art...

A Polish-born artist who lives on...

Left: On the seafront in Perissa by the Monastery of the Holy Cross. Right: Houses in Imerovigli overlooking Skaros Rock. The lower path leading to Theoskepasti Church on the western, or seaward, side of Skaros is clearly visible.

© Robert A. McCabe

It was the summer of 1954 when a young American college student named Robert A. McCabe came to Greece for the first time. He was traveling with his older brother, who’d been invited by a Greek friend from university to return home with him.

A few days after their arrival in Athens, the three young men set off for the Greek student’s hometown. Robert knew only that it was on a small island serviced by boats plying secondary routes; the island, he’d been told, had once been a volcano.

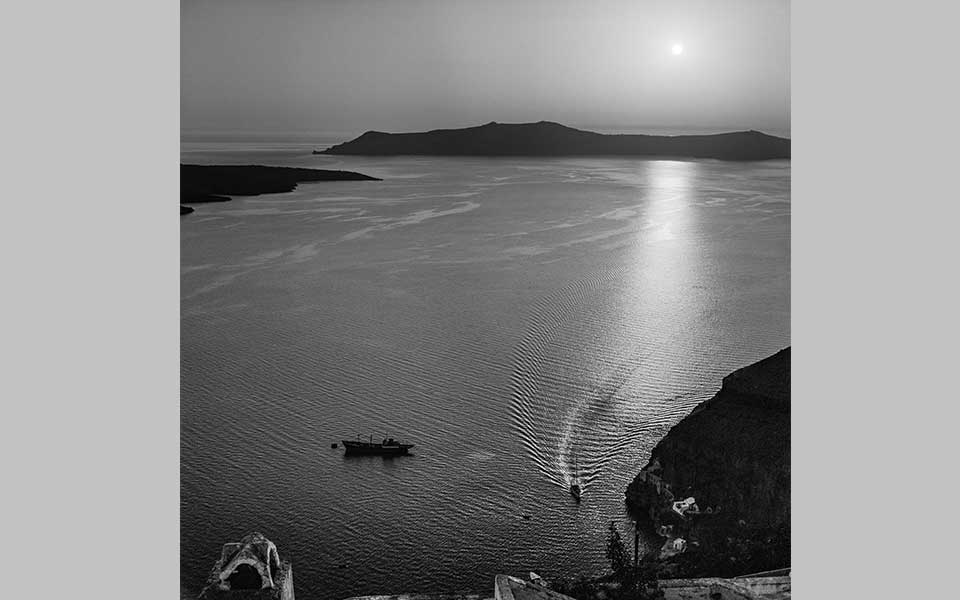

A sailboat arriving, under power, at Yialos just before sunset. A small inter-island freighter is moored at one of the buoys, the sea here too deep for its anchors. Therasia is in the distance, and part of the volcano is on the left.

© Robert A. McCabe

The island’s first bus boards passengers in Perissa for Fira. It succeeded a truck outfitted with benches and a crude canopy.

© Robert A. McCabe

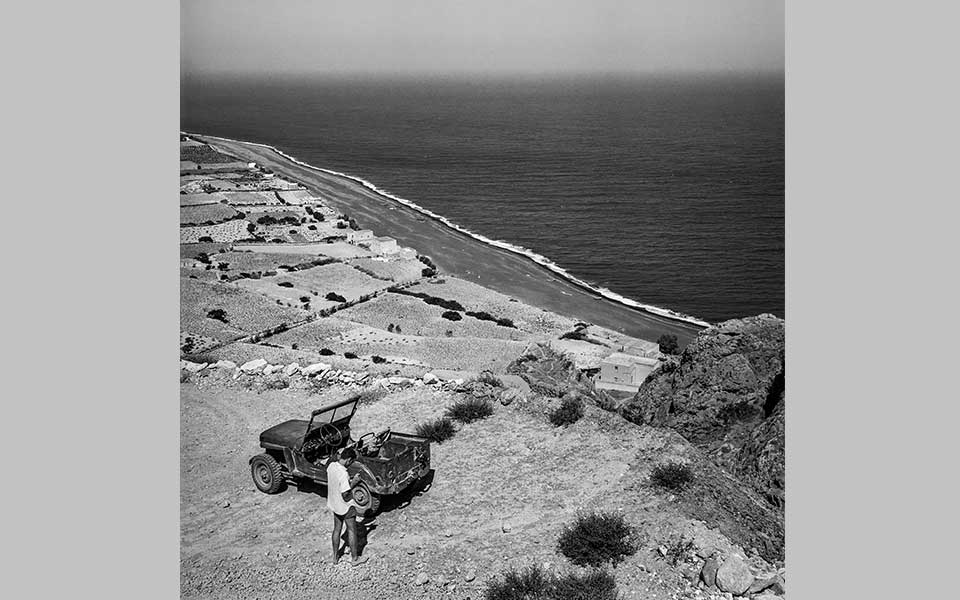

In 1954, Santorini had approximately 12,000 inhabitants and very few visitors. The only modes of transport on the island were a jeep, a small bus and, of course, the island’s mules, on the backs of which the two young Americans, Santorini’s only tourists that summer, rode up from the dock to Fira, the island’s capital.

Over the following days, Robert McCabe would be shown around the island, and the impressions that the land and its people made on him would last forever in his memory. Sadly, the island itself was on the verge of a terrible change. Just two years later, a massive earthquake would strike, destroying or rendering uninhabitable 85% of the island’s houses.

This catastrophe forced a major segment of the island’s population to leave, and the reconstruction program that followed would lay the foundations for Santorini’s complete transformation from a sleepy Aegean island to the cosmopolitan destination that it is today.

The island's single jeep on the road to Ancient Thera. Kamari lies below.

© Robert A. McCabe

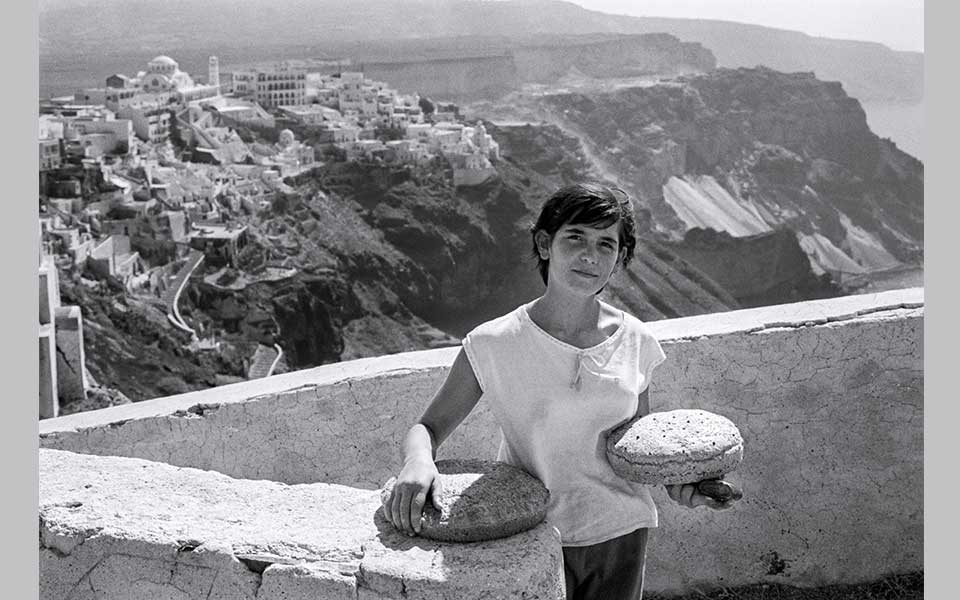

Kalliopi Moudatsou returning from the bakery, in the Catholic quarter of Fira.

© Robert A. McCabe

Happily for us, the young Robert McCabe was already passionate about photography. The photos he took on that first visit, and on the subsequent trips he made prior to 1964, were recently collected and published under the title “Santorini – Portrait of a Vanished Era.”

This impressive volume, which features both texts (by McCabe and by the journalist Margarita Pournara, whose family hails from the island) and photos, captures the Greece that existed prior to mass tourism.

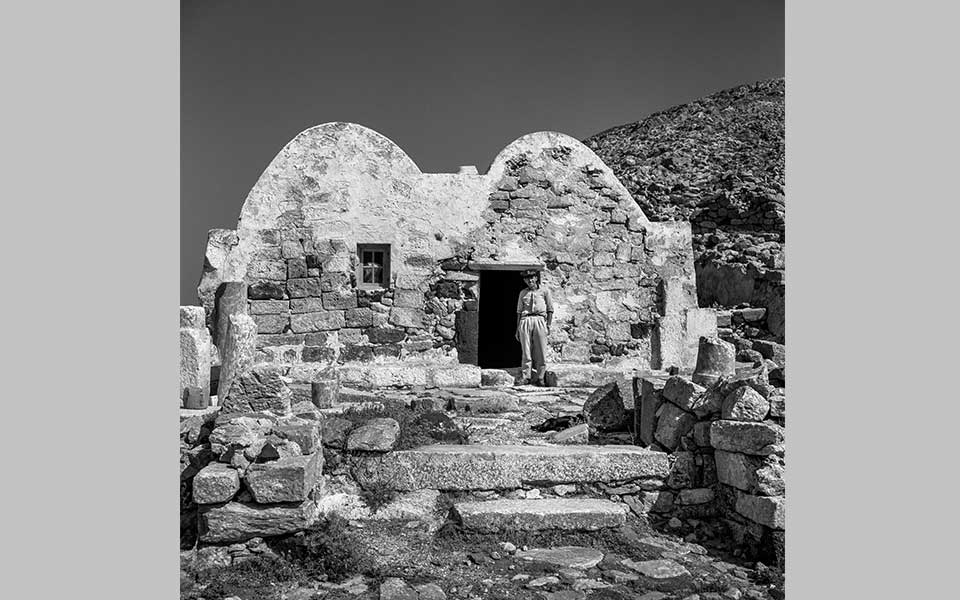

The guard at the site of Ancient Thera, Giorgos Sigalas, stands at the entrance of Aghios Stephanos, a Middle Byzantine-period church built over an Early Christian one, using materials from the ruins of Ancient Thera.

© Robert A. McCabe

A baptism in Emporio. Among those present identified are: Maroulia Karamolegkou, Charalambos “Loumis” Denaxas, Marietta (daughter of “Gerontakis”), Dimitroula Valvi, and Kalliopi Leivadarou.

© Robert A. McCabe

The photographs and the memories of that era that McCabe recounts form an invaluable historical archive for the country, but they also offer a look at the consequences that tourist development has on the land and the people involved.

In the book’s introduction, McCabe writes: “The dramatic changes in the personality and fortunes of the island over the past sixty-five years are what led Margarita and me to undertake this project to document in words and images a Santorini that no longer exists. In a real sense, we regard it as a tribute to the people and traditions that laid the foundation of the island’s current dramatic economic success.”

Below are excerpts from “Santorini – Portrait of a Vanished Era” by Robert A. McCabe and Margarita Pournara:

Outside Loucas’s Restaurant. Takis Roussos, Gerasimos Vlavianos (Loucas’s son), Mrs Vlavianou, Anna Vlavianou.

© Robert A. McCabe

Loucas and his son Gerasimos in front of Loucas’s Restaurant, located next to the Koutsogiannopoulos mansion, which housed the offices of OTE, the telephone company.

© Robert A. McCabe

In 1963, five of us spent six days in Santorini and had two or three meals a day at Loucas’s Restaurant. Each day we would ask for the bill, and Loucas would always say “Later.” By the end of our stay, we knew we had accumulated a huge food and beverage bill, but we had no real fix on the sum.

On the last day, at our final meal, we told Loucas we were leaving and asked for the bill. His incredible response was “Souvenir…souvenir.” He was insistent that we could not pay for anything! It was a gesture that none of us will ever forget. He was in business, struggling to raise a family. What was he thinking? How could this be? (In the end, one of us sneaked into the kitchen and left money under a plate.)

Christoforos “Karoutsos“ Zorzos from Pyrgos, at the Santo Cooperative of Santorini Products, tending to his donkey and to the harvest of cherry tomatoes. He was president of the local farmers’ association for many years.

© Robert A. McCabe

The famous little tomatoes of Santorini are used by Italian and Greek companies in commercial tomato sauces. A native of the island with an engineering degree from a US university decided a little technology could increase the size of the tomatoes and buoy the economy of the island. He brought the seeds to the Demokritos Nuclear Research Center to irradiate them and create large tomatoes.

The process went through many iterations, and finally the scientists were satisfied that they had managed to overcome nature and make the tomatoes large. They tested them near the research center in Attic soil and the tests confirmed their theory! The new seeds were then brought to Santorini with great anticipation. They were planted, and watched, and watched.

Finally, the same beautiful little cherry tomatoes appeared on the vines, with exactly the same circumference as they’d always had.

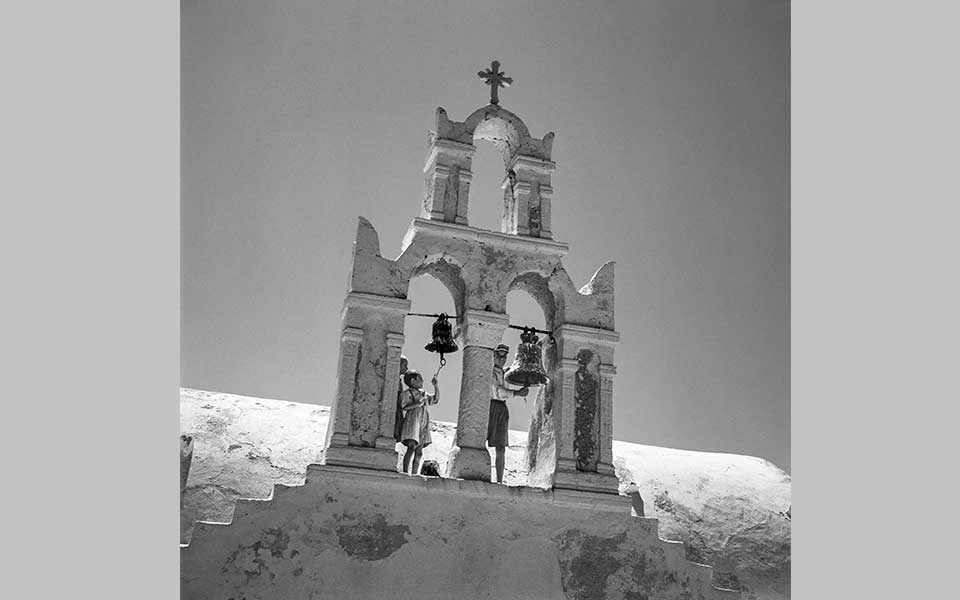

Children ring church bells for a funeral in Fira.

© Robert A. McCabe

The veranda of the Nomikos house after restoration.

© Robert A. McCabe

On an island with no potential for extensive agricultural production, it is the sea that shows the way. As soon as piracy was somewhat curtailed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Santorini emerged as a naval power in its own right, first within the Aegean Sea and, in due course, in the Mediterranean, the Bosphorus, the Black Sea, and beyond – all the way to Gibraltar and the Bay of Biscay.

The secret of its success was that the captains, who owned the boats they commanded, were also merchants: they would transport the famous Santorini wine to the Black Sea and exchange it for grain, which they’d resell in Trieste and Marseille.

In 1842, Santorini boasted 150 vessels, large and small, to its name. The captains from Oia – where the most beautiful kapetanospita (captains’ houses) could be found – owned anything from schooners and brigs to traditional Greek trehandiria.

A Polish-born artist who lives on...

A magical open-air cinema in Kimolos...

As its historic estates fade and...

More and more Europeans retire to...