Reuniting the Parthenon Sculptures: A New Chapter in...

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...

Ramp at the north side of the Sanctuary of Asclepius at Corinth, in 1951.

© Carl Angus Roebuck

In researching how ancient Greek society addressed physical disability, archaeologist Debby Sneed encountered some false assumptions and misconceptions, including a few of her own.

“I, like everyone else, have grown up in a society where we put disabled people in categories, and so I grew up thinking of disability in a very particular way,” Professor Sneed said in a phone interview from California, where she is assistant professor of Classics at California State University, Long Beach.

Her work has shown how ancient Greeks built healing sanctuaries with ramps specifically for people with impaired mobility, providing a practical design solution to a simple problem of access. She has also presented evidence to dispel the belief that ancient Greeks abandoned or killed disabled babies, “the myth of infanticide,” as she calls it.

Professor Sneed, who teaches courses on Greek mythology and on the underworld in ancient Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome, also spends summers in Athens as field director of the ancient Agora excavations, run by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens.

Debby Sneed, archaeologist and assistant professor of classics at California State University, Long Beach.

© Courtesy of Cal State University, Long Beach

Detail of the disabled god Hephaestus with a crutch under his right arm, from the 5th century BCE Parthenon frieze.

© Image copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum

Your research examines accessibility in ancient Greece and how healing sanctuaries included ramps to accommodate people with physical disabilities. Can you talk about those findings?

One of the things that’s important to get from the outset is the distinction between accessibility and accommodation. An accommodation is something that’s added after something’s been constructed to be inaccessible. So it’s fundamentally different from what I saw going on in ancient Greek healing centers, which is that from the beginning, when these buildings were constructed in the 4th century BC, they were built with accessibility in mind.

It’s actually not as surprising as you would think. In the sense that Greeks have a god of healing [Asclepius], and they have these built sanctuaries for that god. And if you’re going to do that, and you want it to be a place that people can visit in order to seek healing, you should probably think about who’s going to use it, and whether or not they can actually get into the buildings. It’s not very different than the sanctuary of Zeus and Olympia having athletic facilities. They have athletic games and so, of course, they’re going to have athletic facilities. It’s a pretty basic form follows function argument.

The only thing that is surprising about it is that we think about things like ramps in terms of accommodations. It’s very difficult for us to imagine that disabled people were considered from the beginning.

Temple of Hephaestus in Athens.

© John K. Papadopoulos

Is there any evidence that the ancient Greeks constructed these ramps for the disabled in buildings other than healing sanctuaries?

The only reason that they are ever necessary is when you have monumental construction where things are elevated above ground level, and that kind of monumental architecture was mostly reserved for religious spaces. In most cases, everyday buildings were constructed at ground level and didn’t require ramps. So yes, the evidence is concentrated in sanctuaries, where ramps were a significant investment in terms of materials, construction time, and space. So there was obviously a prioritization of spaces where larger numbers of people with impaired mobility would congregate, as in healing sanctuaries. That does not include just disabled people. Pregnant women also frequented these healing sanctuaries, as well as elderly people, children, and people carrying things or other people.

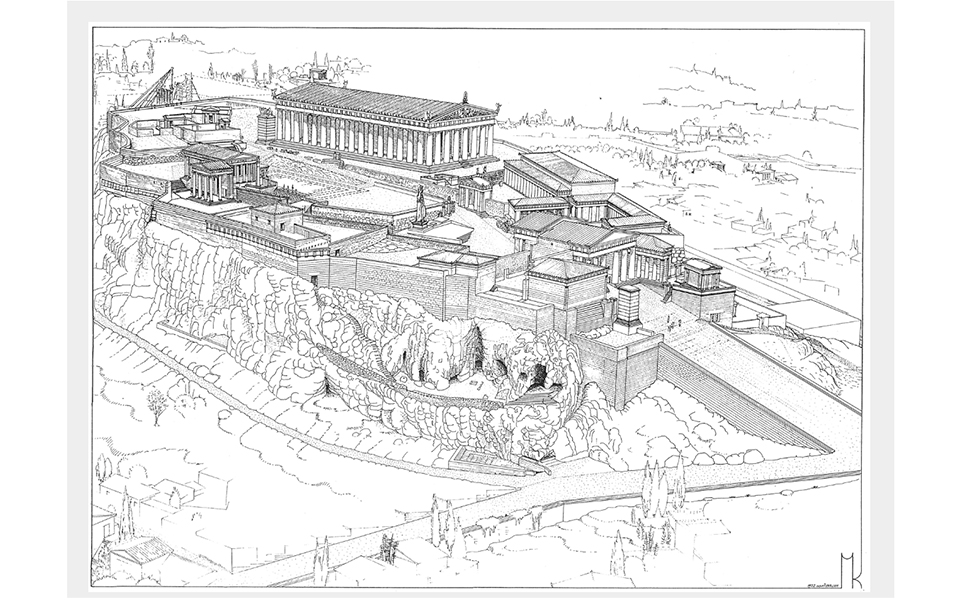

We do see ramps elsewhere. There are a very small number at other sanctuaries, but one of the ramps that I find most significant is the one that leads to the top of the Acropolis. There are stairs now, which were installed in the Roman period, in the 1st century CE, but up until that point, everybody accessed the Acropolis by means of a ramp. I think what really may have been a driving force is the reorganization of the Panathenaea. So, you want to have this festival that culminates with this parade on top of the Acropolis and you want all of the Athenians to participate in it. That includes some of your older members of society. I don’t find it a very complicated argument that that ramp was built with accessibility in mind.

Can you describe some of the misperceptions about how people with physical disabilities were treated in ancient Greece, and the realities of life as a disabled person at that time?

We know that ancient life was hard. Most people were dependent on subsistence farming, and very few lived in comfort—though yes, some did. But when we think about disability in antiquity, we often bring our own modern, ableist assumptions into the conversation. We tend to frame disability through a capitalist lens, where a person’s value is tied to their productivity. In that context, we tell ourselves that our modern societies can afford to support disabled people because we have the financial and social resources to do so. Then we project that logic backward: we assume that ancient societies couldn’t support disabled people because they lacked those resources.

You see this idea even among classicists, that ancient people didn’t have the means to care for disabled individuals. But baked into that argument is the assumption that disabled people were inherently unproductive, that they only took from their communities and didn’t contribute. That’s simply not true, and it reflects more about how we think today than how ancient societies actually functioned.

Reconstruction of the Acropolis ramp, by Manolis Korres.

© Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

You have also researched the issue of infanticide in ancient Greece. What did you find?

The biggest example is this myth that disabled babies were killed at birth. You’ll hear people say this broadly about all of ancient Greece, or sometimes specifically about Sparta. Even scholars who are sensitive to the politics of the ancient world will repeat the claim that there was a rule in ancient Sparta to kill disabled infants.

In fact, we have no evidence that this happened, and we have a lot of evidence suggesting that people encouraged the survival of infants who were weak or disabled. And so you can never have 100% certainty. All of our arguments are circumstantial. But I think that the weight of the evidence points towards this not being a practice.

What can we learn from how ancient Greeks addressed physical disabilities?

We should never use ancient Greece or Rome as a model for our society today. It doesn’t make any sense. Their realities were very different from ours. But there is nothing inherently natural about the way that we think about disability, or the way that we treat disabled people.

There are other ways of doing it. We can think about building design, going back to the ramps. We can see that ramps don’t have to be an afterthought. Actually, you can integrate them into the design in a very thoughtful way. They can be integral to the appearance, to the aesthetics of architecture. Ramps now tend to be very ugly. They tend to be hidden away on the side or backs of buildings. They’re unattractive features, but they don’t have to be. They can be made out of stone, they can be right at the front as they were on some of these ancient Greek buildings.

As you survey the modern city amid the ancient ruins, what strikes you when you consider that the Athens of today is a very inaccessible place, especially for the disabled and elderly?

I don’t want to make it seem like ancient Greece was some utopia for disabled people. It was not. But when you look at the modern city you can see very much that it is built for people who are fully able-bodied. That doesn’t mean of course that there aren’t disabled people or elderly people or pregnant people or children. It doesn’t mean that it’s even safe for nondisabled people, right? Athens can be chaotic. It’s not necessarily worse than other cities, though in some ways it is. I still don’t know who thought marble sidewalks were a good idea. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t opportunities for people to thrive. You see a lot more investment by the EU in disability accessibility. You see things like making cultural heritage accessible for example with the elevator or the paving on top of the Acropolis. Those changes benefit everyone, not just disabled visitors. Before the paving, the Acropolis was genuinely dangerous. People slipped all the time.

Reconstruction of the 4th century BCE Temple of Asclepius at Epidaurus in foreground, with the ramp extending from the front in the background the thymele, also with its ramp.

© Copyright-2019,-J.-Goodinson

When accessibility structures were installed at the Acropolis a few years ago, some critics felt the designs interrupted the flow of the site. Did you encounter any related criticism in ancient Greece to ramp construction?

There wasn’t any discussion about it because there were no civil rights, people weren’t thinking about disabled people as a group. People in ancient Greece just weren’t thinking about this. There wasn’t a hierarchy whereby they thought “you’re worse and we’re better.” So when a ramp was built at a healing sanctuary, for instance, it was just practical.

You’re now writing a book that expands your research on physical disability in ancient Greece. Tell us more about that.

I’m looking at various aspects of ancient life and ancient society, like marriage and childbirth, military service, labor and employment, religious practice. And my question is, if ancient Greeks were expected to participate in these rights of passage, were disabled people expected to participate in them as well? If they were, what happened to their sense of belonging if they couldn’t because of their disability?

It’s not about whether disability was viewed as good or bad, or whether disabled people were liked or disliked. We have a lot of evidence of disabled people serving in the military as generals, as members of the cavalry and as members of the infantry. We also have evidence that there were formal exemptions of people who couldn’t participate in military service.

You can ask similar questions about marriage and childbirth. In ancient Greece, people were expected to marry and have children. People chose not to marry for all sorts of reasons, and disability might have been one of them, but the expectation was still there. And that’s very different from how we tend to think today. And that makes it fundamentally different from the ways we think about it. In modern contexts, we often adopt a kind of paternalistic or “benevolent” attitude toward disabled people, but we don’t necessarily expect them to fulfill all the same social roles.

And it’s clear that the ancient Greeks lived with people with disabilities, they revered people with disabilities. Those people were very much a part of life.

And that’s one of the points of my book: that disability was just a part of life in the ancient world. This idea that we have of ancient Greeks looking like Greek statues come to life – everybody’s got this fit, hot body, everybody is thin, everyone is athletic – is ridiculous. They had human bodies and they had all of the nonsense that comes along with that.

How often are you in Greece for research, and is it still special to visit?

I work in Athens in the summer at the Agora, and I love going to Greece. I love the culture. I love the city. I love all the neoclassical architecture; Plaka is my favorite neighborhood. The food, of course. I love Athens.

You are field director of the ancient Agora excavations, run by the American School of Classical Studies. Were there healing sanctuaries within that sprawling complex?

There is no healing sanctuary there that we’re aware of. Of course, disability is not absent from the Agora. The entire Agora is overshadowed by the temple of Hephaestus [the Greek god, who was himself disabled].

Finally, do you think there’s a bit of exceptionalism in the view that ancient Greek society couldn’t have done as much as we do today to help physically disabled people?

Yes, absolutely. The Greeks had hundreds of gods and defined divine beings, but only twelve core Olympians. And one of them is disabled. That is a cultural choice that the Greeks made. A bunch of other gods are not in that core twelve. Hephaestus had a congenital mobility impairment and yet he’s one of the major gods. And he’s a craftsman, so people have tried to come up with all sorts of reasons. They’ll say, “He’s not like the other gods. He’s an outlier.” And my response is, to whom? Not to the Greeks. If he was an outlier to the Greeks, they wouldn’t have included him in the core Olympian twelve. He doesn’t fit neatly into the mold of the other gods, but he’s there. And he’s disabled.

His disability is simply part of who he is—not the reason he’s revered or something to be overlooked. He’s a craftsman, a creator of tools and machines. And that brings up something we talk about today: the link between disability and creativity. Living with a disability in an ableist world often requires a huge amount of creativity—finding new ways to use things that weren’t built with you in mind. I think we see a version of that in Hephaestus. He has one of the most prominent temples in Athens, right in the Agora. The Athenians didn’t worship him despite his disability. They didn’t worship him because of it either. They just worshipped him, and he happened to be disabled.

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...

From temples and festivals to front...

From olive presses and traditional costumes...

A compact archaeological guide to the...