The Long Road Home: The Battle for the...

Two centuries of dispute, diplomacy and...

Statuary from the east pediment of the Parthenon, on display at the British Museum. Created under the direction of master sculptor Pheidias c. 430 BC, they were forcibly removed from the temple façade in the early 19th century by agents of Lord Elgin, then British Ambassador to the Ottoman empire.

© Kirsty Wigglesworth / AP Photo

For over two centuries, the Parthenon Sculptures have been at the center of one of modern history’s most enduring cultural disputes. Removed from their original home in Athens by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, these 2,500-year-old masterpieces have been housed in the British Museum in London since 1816, fueling impassioned debate over their rightful location.

In 2024, renewed negotiations have brought the possibility of reunification closer than ever. Professor Irene Stamatoudi, a former Greek government adviser, told the BBC that a deal is “close,” while Professor Nikolaos Stampolidis, director of the Acropolis Museum, expressed optimism to The Observer: “We are making remarkable progress, and developments are in our favor.” Public support in the UK and a broader cultural shift in Europe have injected fresh momentum into the campaign, with many viewing this moment in time as a potential turning point.

The incomplete nature of this vivid cavalcade scene from the Parthenon frieze, the whole of which is currently split between Athens and London, is a powerful symbol of the campaign for cultural reunification.

© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

The past year has seen significant progress in the campaign for the Parthenon Sculptures, marked by diplomatic overtures, grassroots advocacy, and shifting political attitudes. George Osborne, former UK Chancellor and chair of the British Museum, has sought to broker an innovative agreement with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The proposed deal includes loaning portions of the Parthenon frieze to the Acropolis Museum in exchange for Greek artifacts, though specifics remain unclear.

In May, UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin (ICPRCP) met in Paris to address the issue. Greece reaffirmed that the sculptures are an integral part of its cultural heritage and urged the UK to comply with UNESCO recommendations. The committee called for intensified negotiations, voicing concern over the lack of progress.

Grassroots advocacy has also been pivotal. In the lead-up to the UK’s July General Election, the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles (BCRPM) launched a campaign urging citizens to pressure members of Parliament into supporting reunification. “It is crucial for UK citizens to voice their support for the reunification of these cultural treasures,” a committee member emphasized, underscoring the positive impact on UK-Greece relations.

In October, The Parthenon Project hosted a high-profile event in Athens titled “A Win-Win Solution for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures.” Proposing a cultural partnership, they suggested that Greece could loan blockbuster artifacts like the Mask of Agamemnon and Kritios Boy in exchange for the sculptures. “This is not about dividing culture,” project founder John Lefas told the Greek City Times, “it’s about creating new opportunities for learning, sharing and celebrating our common history.”

In early December, Prime Minister Mitsotakis met with his UK counterpart, Sir Keir Starmer, in London, framing the debate as one of cultural justice rather than ownership. Starmer, while reiterating that the British Museum’s trustees hold final authority under the British Museum Act of 1963, signaled openness to a loan agreement. Mitsotakis contrasted the meeting with the frosty reception he received from then-Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak a year earlier, noting that Labour’s victory in the summer election marked a pivotal opportunity. Greek Culture Minister Lina Mendoni urged patience following Mitsotakis’ visit, emphasizing Greece’s commitment to diplomacy. While significant challenges remain, the shifting tone of political and cultural discourse suggests a breakthrough may be within reach.

Iris, goddess of the rainbow, from the Parthenon’s west pediment, was among the sculptures whose removal and sale to the British government in 1816 drew widespread condemnation from scholars, artists and poets, including renowned philhellene Lord Byron.

© THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

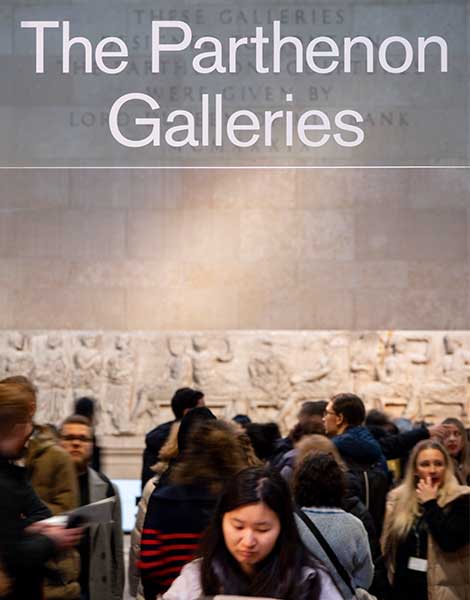

In the Parthenon Galleries of the British Museum are sections of the Parthenon frieze; which vividly depict the Panathenaic procession. Advocates for their return to Athens argue the display presents a fragmented and decontextualized narrative.

© Mike Kemp / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

Public sentiment in the UK continues to shift dramatically in favor of returning the sculptures. An early December YouGov poll revealed that nearly 60% of Britons support their return to Athens, citing cultural justice and historical integrity. This growing support places increased pressure on the British Museum’s trustees to weigh ethical considerations against legal and logistical constraints.

Developments in 2024 also reflect broader global trends. Across Europe, cultural restitution efforts have gained traction. In 2022, Italy set a precedent by permanently returning the Fagan Fragment, a piece of the Parthenon frieze, to Athens. Hailed as a model for international cooperation, the move underscored the importance of cultural heritage. As Artnet News observed, “The movement to return fragments of the Parthenon Sculptures is a harbinger of broader restitution efforts.”

This growing emphasis on cultural justice has reshaped the debate, lending new momentum to Greece’s cause and aligning with evolving perceptions of historical accountability.

Half of the surviving Parthenon Marbles have been on display in the British Museum since 1817.

© Shutterstock

Despite significant progress, obstacles remain. The British Museum continues to assert legal ownership, citing its acquisition of the sculptures in 1816. The 1963 British Museum Act prohibits the permanent deaccession of objects, complicating negotiations.

The UK government maintains that the museum’s trustees have ultimate authority over the sculptures’ fate. As the Financial Times noted, “Any final decision lies with the Trustees of the British Museum, not the UK government, reflecting the institution’s independence.” Greece has indicated willingness to accept the sculptures as a deposit, allowing Athens to display them without challenging British ownership. However, this compromise is far from assured, with legal and logistical issues still unresolved.

Despite these challenges, optimism surrounding reunification continues to grow. Greek officials have hailed recent developments as unprecedented. Culture Minister Lina Mendoni emphasized, “The reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures is not just a Greek issue; it is a matter of global justice.”

Momentum (from initiatives such as The Parthenon Project, grassroots activism and broader international restitution efforts) has created a sense of inevitability around the sculptures’ return. As the Financial Times remarked, “2024 marks a turning point where both sides are closer than ever to a compromise.”

Young advocates and cultural organizations have played a vital role, ensuring the conversation remains dynamic and forward-looking. Their efforts have amplified calls for restitution, resonating with a global audience and reinforcing the campaign’s alignment with shifting attitudes toward cultural heritage and justice.

The strides made in 2024 demonstrate the power of collaboration and cultural diplomacy. Reuniting the sculptures would honor Greece’s cultural legacy while setting a precedent for resolving similar disputes worldwide.

As cultural institutions adapt to evolving notions of historical responsibility, the Parthenon Sculptures stand as a powerful symbol of international cooperation and shared heritage. Whether 2024 will prove to be the definitive turning point remains uncertain. What is clear, however, is that the dream of reunification is no longer a distant aspiration – it is an achievable goal, within reach.

Two centuries of dispute, diplomacy and...

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

A personal exploration of Koukaki and...