A Green Oasis Near Ηania: The Botanical Park...

Where tropical fruit trees thrive beside...

© Dimitris Tosidis

The haunting soundscape of the White Mountains speaks in wind through the gorges, birdsong, goat bells, and echoing thunder. It’s been captured by environmental engineer and PhD candidate Christina Georgatou of the Hellenic Mediterranean University, as part of her research into acoustic ecology in protected areas.

Other projects tell parallel stories of this place. The Postman’s Route, a documentary project and digital archive curated by Penelope Gini, preserves the memory of a 45-kilometer walking path once used by local postal workers to deliver mail to the region’s isolated villages between 1900 and 1985. A website, agios-ioannis-sfakia.com, documents everyday life in the village of Aghios Ioannis, seen through the lens of a young Norwegian couple who lived there for a year in 1979, when the population stood at just 55. Most recently, in December 2023, Giorgos Patroudakis published Apocosmos, a photographic chronicle of transhumant shepherds in the highlands of the Madres, where survival persists without electricity, running water, or roads.

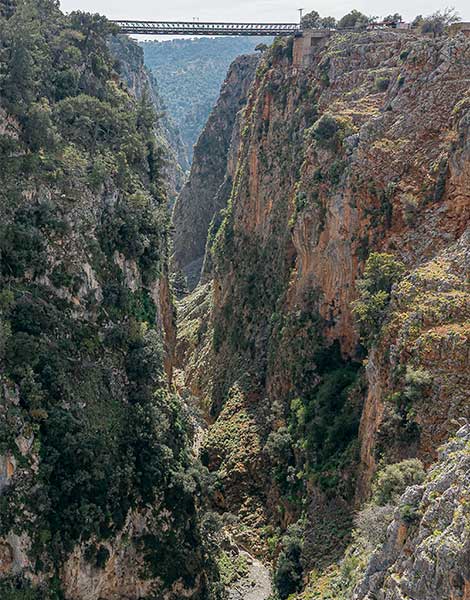

All these projects, each in their own quiet way, highlight the unique character of Sfakia, a place shaped entirely by the impassable terrain of the Lefka Ori (White Mountains). With more than 50 peaks rising above 2,000 meters, alpine plateaus, vertiginous gorges (one theory suggests the word Sfakia stems from sfax, meaning “cleft” or “chasm”), and dense pine forests tumbling toward the Libyan Sea, this topography has dictated life for centuries.

The Aradena Gorge and the bridge, which was constructed in 1986.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Hora Sfakion, the seat of the municipality, where the road ends and the ferry 'Daskalogiannis' takes over transportation.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Even today, most of the region remains without road access, a fact that has not only preserved biodiversity and traditional ways of life but also continues to shape the temperament of its people. The Sfakians are known for being private and resilient, traits born of geography as much as culture. Here, space has always been paradoxically both vast and constrained.

Every revolt in Sfakia’s long history has been fought over these mountains. For past generations, they were a vital source of sustenance and safety, and they still command the same reverence. Young locals continue to protect the land and its rare inhabitants: the bearded vultures, the endangered kri-kri goats, the elusive Cretan wildcat, and hundreds of native plant species, including 25 found nowhere else on Earth.

The old ways also survive: cheese is still made using millennia-old techniques. In the Madres, cheesemakers still use domed stone huts known as koumoi, built entirely without mortar, in the ancient, corbelled technique.

Even the land itself remains fiercely protected. Nearly all Sfakia is privately owned – public land is virtually nonexistent – and locals do not sell. It took decades to push through road construction projects, and even then, the road was never completed; when Samaria Gorge was declared a national park, development ground to a halt.

Livaniana, the village above the beaches of Finikas and Lykos, has not been permanently inhabited in recent years.

© Dimitris Tosidis

There was a time when living by the sea in Sfakia meant privilege. The coastal ports of Hora Sfakion, Loutro, and Aghia Roumeli were once thriving. Loutro played a prominent role even in Hellenistic times, as one of the two harbors of the ancient city of Phoenix.

“It was safe in all weather conditions except during sirocco winds, while the adjacent harbor of Phoenix was safe only during sirocco winds. Ships from all over the Mediterranean knew they could seek shelter here,” says Gianna Patroudaki, a local business owner from Loutro. “This tiny place even minted its own coin. In 1821, Loutro became the capital of revolutionary Crete. You can’t say it was ever left behind just because there was no road.”

This proximity to the sea shaped not only livelihoods but outlooks. Many Sfakians became sailors, developing more outward-looking mindsets than their inland neighbors. The same was true of residents in Hora Sfakion, now the administrative center of the region, which had a commercial port and hosted most public services.

In Sfakia, sheep are called 'oza' and goats 'aiges'. They are not guarded by a shepherd, as there are no threats.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Aghia Roumeli, once the site of the ancient city of Tarra (which also minted its own currency), was similarly vibrant with activity. “Up until the 1960s, there were six or seven water mills operating inside the Samaria Gorge,” recalls Andreas Stavroudakis, a local restaurateur. “People even came from Mesara in Heraklion to grind their grain here.” The surrounding forests were privately owned, and locals lived from logging; there was even a water sawmill, and they also harvested pine resin. At the time, there were more than 35 inhabited homes in the old village of Aghia Roumeli, and the school had at least as many students.

Roussios Viglis, now 75, spent his childhood in Aghia Roumeli and remembers those years well. A beekeeper and hotel owner, he still returns every summer, moving his hives to take advantage of the gorge’s wild flora. As a boy, he would scan the cliffs with binoculars for wild goats and sleep under the stars in the ruins of the old Samaria village, nestled halfway through the canyon.

As if people take on the habits of animals, like another wild goat, Antonis Georgedakis on the cliffs above Aghios Pavlos.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Few places in Crete were more isolated than the now-abandoned village of Samaria. Hidden deep within the gorge that shares its name, it was accessible only on foot from Xyloskalo in the north or Aghia Roumeli in the south. In winter, it became completely cut off: snow blocked the northern passes, while rising waters blocked the southern exit at the narrowest section of the gorge, known as the Portes. The only way out was via dangerous side trails.

Still, people lived there until the 1960s, when the gorge was declared a national park. The village, down to its last five residents, was expropriated and eventually emptied.

“Many of the women there had never left Samaria. They had no idea what the city was like,” says Yiannis Georgedakis from the village of Aghios Ioannis. “Back then, the worst curse you could put on a Sfakian woman was: May you marry a man from Samaria.”

Like giant snakes, the roads in Sfakia — as in other parts of southern Crete — try to tame the rugged terrain.

© Dimitris Tosidis

Aghios Ioannis itself remained roadless until 1988. The terrain – particularly the sheer drop of the Aradena Gorge – had long made road-building impossible, until the Vardinogiannis family, which hails from the village, funded the construction of a bridge in 1986. Yet even then, infrastructure wasn’t enough to halt depopulation. Aradena had already been devastated by a deadly blood feud in the 1950s.

Yiannis’s son Antonis grew up in Aghios Ioannis, as did his wife Anna, originally from the neighboring village of Livaniana. Back then, the village had about 40 residents, all of them shepherds. To reach Anopoli or Hora Sfakion, they would walk or ride mules up the stone stairway that zigzags the Aradena cliffs.

Today, the paved road ends in Aghios Ioannis, right beneath the towering peaks of the Lefka Ori. Just eight elderly residents remain, but the village sees a steady flow of visitors, drawn by the silence, the solitude, the unspoiled trails leading to Mount Pachnes, the chapel of Aghios Pavlos, and Aghia Roumeli.

Antonis and Anna have run Alonia, their rustic guesthouse, for over 25 years, continuing the legacy of the mountain shelter started by Antonis’s father. After a brief stint away from the village, the couple returned to build their life here, welcoming guests from all over the world who come not despite the remoteness, but because of it. No phone signal, just homemade meals and the endless call of the mountains.

Shepherds still pass through, heading to their mitata – stone dairy huts – in the highlands. Others climb up from Anopoli, the quintessential shepherd village of Sfakia. In summer, its 200 residents bring their flocks to graze on the alpine slopes.

“Up there,” says beekeeper and herder Stavros Kriaras, “you just lift your hand, and you can touch God.” He speaks of malotira, the fragrant mountain tea that grows wild and thick like grass, of cypress trees twisted by time and wind into fossil-like forms, and of the “mountain desert” that stretches out beneath the peaks. “We stay there from May until the snow drives us down again.”

Manolis Patroudakis, one of the three or four residents of Loutro.

© Dimitris Tosidis

At the Church of the Holy Trinity, dating back to the 14th–15th century, in Agia Roumeli — which locals call "Aghiá Roméli", meaning "the waters of the Greeks".

Today, it’s the coast – not the mountains – that feels isolated. The seaside villages of Sfakia, including Loutro and Aghia Roumeli, as well as the awe-inspiring beaches of Glyka Nera, Marmara, Aghios Pavlos, and Domata, remain inaccessible. They are reachable only by sea – via water taxis, small ferries, and the regional passenger boat – or by footpaths along the legendary E4 hiking trail – islands within the island.

In Aghia Roumeli, the isolation is tangible. Only five residents stay through the winter, swelling to around 50 in summer, when more than 15 small businesses open. Yet even then, most visitors don’t stay. Around 800 hikers pass through daily after descending the Samaria Gorge – and then leave. Those who do stay come for the silence, the wide beach, the beauty of the preserved village architecture, the castle hike, the abundant spring water, and the lush vegetation.

Locals believe that both the number of permanent residents and overnight visitors would grow if there were easier access. Many still feel uneasy. Twice in its modern history, the village has suffered deadly flooding from the river. It was this same river that forced residents in the 1980s to abandon the old village and build a new settlement on the beach.

Aghia Roumeli is 8 nautical miles from Sougia and 9 from Hora Sfakion. It doesn’t even have a proper harbor. “We can’t even fish,” says Roussios Viglis, “because there’s no port. Maybe it’s time we revolt again.”

Stavros Kriaras, a beekeeper and livestock farmer from Anopoli, takes his animals up to the Sfakian Madaras in the summer.

© Dimitris Tosidis

The Samaria Gorge opened the region to tourism. In the late 1980s, nearly 2,000 hikers passed through daily. “Even now, the numbers are high,” says Andreas Stavroudakis, “but they should be lower. There should be regulations to prevent accidents.” For locals, Samaria is not a tourist attraction. It’s a demanding natural passage that requires stamina and respect.

In Loutro, tourism arrived earlier. Manolis Patroudakis, a retired fisherman and former taverna owner, remembers the first three English tourists who arrived in 1960, when he was just 10. “Some beautiful old homes still stood back then,” he recalls. He tried going to sea, but returned quickly. “I was born here; I grew up here. I don’t belong anywhere else.”

After a lifetime of swordfish and lobster fishing, he now spends his days in his “tower” near the well-preserved castle, carving driftwood collected from the mountains and staying out of the way of the 1,000+ daily visitors who descend on Loutro in high season. The influx is made easier by the frequent boats from Chora Sfakion, and the E4 trail connecting the two villages can be walked in under an hour. A short side trail leads to the paved road ending at nearby Phoenix.

Life in Loutro is simpler. As Michalis says, “You need heart to live here in the winter.” It’s not true isolation – only about ten days a year are fully cut off – but the solitude is real.

Helping keep the region connected is Anendyk Seaways, a local maritime cooperative. Its boats – Daskalogiannis (linking Hora Sfakion, Loutro, Aghia Roumeli, Sougia, and Paleochora) and Samaria (a subsidized ferry that connects Gavdos) – are a lifeline. “Our goal is to keep locals and young people in Sfakia,” says Stratos Bournazos, the company’s captain and president. Originally from Apokoronas, he moved to Sfakia in 1986. “This landscape still takes my breath away – high mountains and sea, side by side.”

But he’s quick to point out the region’s most pressing issue: inadequate ports. “Paleochora and Chora Sfakion have only basic fishing harbors. In Loutro, we just have a calm cove and a simple pier. And in Aghia Roumeli, there’s practically nothing.”

© Dimitris Tosidis

Most residents of Aghia Roumeli want a road, and most Sfakians agree they have every right to. To deny someone access in the name of preserving natural beauty can feel hypocritical. And yet, everyone also knows that it’s precisely this lack of roads, this absence of noise, this rare quiet, that both locals and visitors cherish.

They know, too, that building a road would mean destroying part of the E4 trail, interfering with a protected Natura 2000 zone and a national park. It could mean covering the archaeological site of Loutro, altering the endless pine forest of beloved Selouda, and suddenly dealing with dozens of cars in villages that have no infrastructure to receive them.

They’ve seen what roads can bring. Livaniana, despite its paved access, was abandoned. Phoenix and Lykos remain uninhabited. Would a road change this fiercely preserved landscape? Could it unravel a culture that has withstood the ravages of time? However, some believe access could keep younger generations in the mountains, continuing age-old pastoral traditions. It could save lives in an emergency. Perhaps Manolis Patroudakis says it best, half-joking: “I want the road, yes – for emergencies. But not too close to my hideaway.”

Stavros Kriaras hopes for a road to the Madres, the alpine grazing lands. “But it should be for us,” he says, “not for just anyone. Our mountains are untouched places – and we protect them.” These are the same people who once stood up to conquerors. The same people who today are ready to defend their mountains from the threat of wind turbines. No one knows for sure whether a road would help or how it might change life here. What they do know is this: what Sfakia needs most right now isn’t asphalt. It’s safe, functional ports.

Where tropical fruit trees thrive beside...

Cretan cuisine lives on from home...

The roads may twist and climb...

With fewer tourists, sunlit harbors, and...