What to Do οn Syros this Summer

Discover festivals, beaches, food, and hidden...

View from the Byzantine castle. On the left, windmills can be seen, built between the 17th and 19th centuries.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

She kneels at the roadside, her bicycle parked nearby, angling the lens to frame the moment more precisely as the tangerine sun slips behind the hill. Heidi is an experienced photographer, but this landscape – and this light – is new to her. Just then, a red pickup truck stacked with hay slows as it passes. Inside are Michalis and his son Giorgos, heading to the sheepfold for their evening feeding.

It’s a scene from Leros that, taken in isolation, could easily be mistaken for a snapshot from the 1970s. Moments like these – now increasingly rare in an age of overtourism and lost innocence – are scattered across this quiet island, hiding in plain sight. And while Leros was never exactly known for carefree living, such glimpses now coexist with a more complex history one that continues to shape the island’s identity.

Different architectural styles meet in the settlements of Leros.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Building in Lakki, in the style of Italian Rationalist architecture.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

That contrast may be one of the reasons why so many foreigners have chosen to settle here. What they find is a rare combination: the simplicity of another era paired with the comforts a modern traveler craves. A small community where everyone knows each other, distances are short, doors are left unlocked, and a rare, enveloping calm permeates daily life.

Leros has remained largely untouched by the sweeping waves of tourism that have transformed so many other Greek islands in the latter half of the 20th century. One reason is its decades-long association with the State Psychiatric Hospital, which opened in 1958. But the island’s layered history begins earlier – with the Italians.

Aghia Marina

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Kokkina, one of the island’s many unspoiled beaches.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

On May 12, 1912, Italian forces occupied Leros and quickly recognized its strategic significance. The port of Lakki, one of the largest and deepest natural harbors in the Aegean, was deemed ideal for use as a naval base. The Italians renamed it Portolago and embarked on an ambitious plan: to build a model town around the bay.

The city plan was officially approved in 1934, and within less than a decade, a new town had emerged, complete with a school, church, town hall, movie theater, hospital, hotel, marketplace, and residential blocks. For a time, the Italian population on the island even outnumbered the local Greeks.

Buildings constructed by the Italians, later used by the State Psychiatric Hospital.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

At the same time, the Italian military fortified the island with lookout posts, barracks, and tunnel networks, which would prove crucial during World War II. Early in the war, Leros was bombarded by the British; later, following Italy’s surrender in 1943, the Germans launched their own assault.

The Battle of Leros lasted 52 days – from September 26 to November 16, 1943 – and became one of the most significant military engagements in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was also one of the last German victories in the region, leaving behind a seabed littered with sunken ships and aircraft.

The day's catch at the port of Aghia Marina.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Every afternoon, the shepherd Michalis heads to the pen to feed his animals.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

When the Dodecanese islands were officially united with Greece in 1947, the Italians departed, leaving behind a substantial infrastructure. Among these remnants was the naval base at Lepida, just across from Lakki. This extensive complex would go on to shape the island’s fate for decades to come.

In 1949, the site became home to the Royal Technical Schools, which hosted more than 16,000 children and adolescents from the so-called Paidopoleis, state-run “children’s towns” established under Queen Frederica’s postwar welfare programs.

But it was the island’s large, vacant buildings and its geographic remoteness that led to a different kind of institution being established in 1958: the Leros Psychiatric Hospital. At the time, a sign on the premises read “Colony of Psychopaths” – a stark reminder of the era’s stigmatizing views of mental illness.

Icon painting in the chapel of Aghia Kyra, created by political exiles.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Military artifacts from World War II in the private collection Deposito di Guerra.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

At its peak, the hospital employed hundreds of locals, creating an economy largely independent of tourism. But the island’s identity became further entwined with marginalization. During Greece’s military dictatorship (1967-1974), Leros was used as a place of political exile. According to the locals, “People have always come to Leros who didn’t want to be here” – a phrase that continues to echo today, especially since the establishment of the migrant reception center currently operating above the former psychiatric facility.

In 1989, The Observer published photos exposing the appalling living conditions at the Leros asylum. The images shocked international audiences and triggered a long-overdue reckoning in Greek mental health policy. What followed was a slow and challenging process of deinstitutionalization, supported by mental health professionals from around the world who came to study and reform the system.

Many patients were transferred to facilities elsewhere in Greece; others began the difficult journey toward social reintegration, often within the very community of Leros. Today, a few dozen still live on the island in independent housing. Many are employed by Greece’s first mental health social cooperative, founded in 2002 as part of the Dodecanese Mental Health Sector. The cooperative cultivates herbs and aromatic plants and produces honey at Caserma of Herbs, a working farm in the area of Koulouki that is open to visitors.

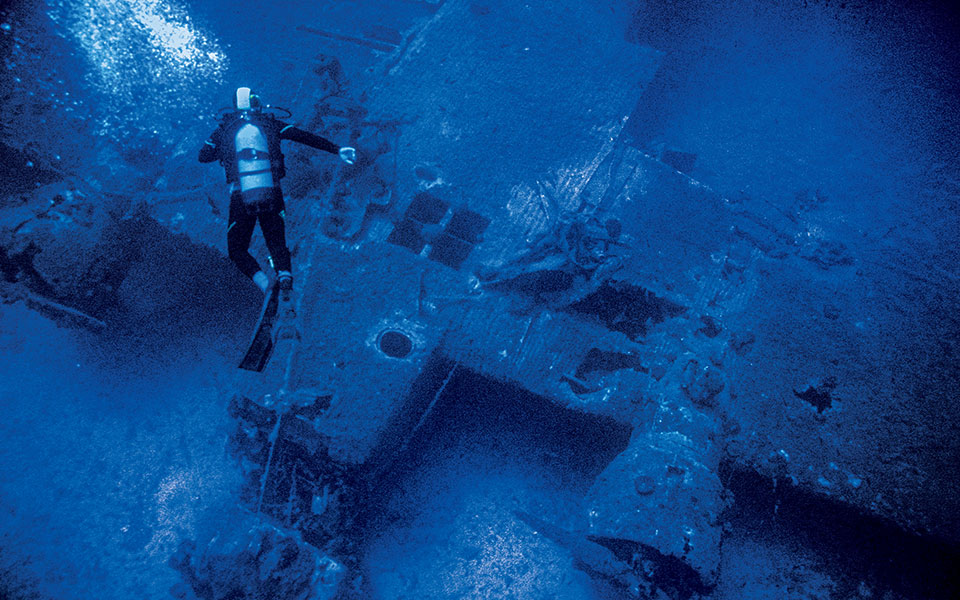

Nine shipwrecks from World War II rest on the sea floor surrounding the island.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

It’s hard to visit Leros and not be struck by its layered, often complex history – even if it contrasts with the carefree spirit most travelers associate with Greek summer holidays. One of the most meaningful ways to engage with the island is to take a walk around Lakki, the island’s main port town, and admire the striking examples of Italian Rationalist architecture built during the interwar period.

Off the coast at Krithoni, a well-run and welcoming dive center offers visitors the rare chance to explore nine World War II shipwrecks – haunting reminders of the fierce battles that once raged around the island.

History is equally tangible inland. One of the island’s most notable sites is the War Museum, housed inside an Italian-era tunnel carved into the hillside, where wartime artifacts are carefully curated and exhibited. A similar atmosphere can be found at Deposito di Guerra, a private collection of dozens of items – from uniforms and weapons to naval mines and military maps – all open to the public.

Also worth visiting is the small chapel of Aghia Kioura, a site often included in the few travel guides available for the island. Between 1968 and 1971, during Greece’s military dictatorship, exiled political prisoners repaired and painted its interior, creating a place of quiet resistance through sacred art. On the western side of the island, above the area known as Gerakas, you’ll find a curved acoustic wall, an early form of radar used by the Italian air defense to detect approaching enemy aircraft.

As part of a growing effort to highlight this rich historical heritage, the town of Lakki is now restoring its iconic Leros Hotel, which was originally built by the Italians as Albergo Roma.

Yet Leros is more than its past. With a year-round population of around 8,000, the island is very much alive in both spirit and activity. Since 1989, a local theater troupe has staged six to seven productions each year, with over 30 active members. Fanouris Kontogiorgakis, a decorated cycling champion, has created Leros Bikes, through which he offers guided bike tours for visitors. He also maintains trails, teaches cycling to local children, organizes tree-planting initiatives, and repairs wheelchairs free of charge – a quiet force of good in a small, close-knit community.

At Mylos in Aghia Marina, for creative seafood dining.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Of course, the “classic” ingredients of a Greek island holiday are here too. Leros boasts a wide variety of beaches – some serviced, others unspoiled – but none overrun by crowds or umbrellas, even in the heart of August. Along the shoreline, unpretentious seaside tavernas serve up freshly caught fish and top-quality seafood brought in daily by the island’s many fishing boats.

Its settlements may not conform to the typical postcard image of the Aegean, but they offer a distinctive charm all their own. Lakki with its unique architecture and Aghia Marina with its cluster of neoclassical buildings and the Byzantine castle towering on the opposite hilltop invite slow exploration and discovery.

Still, the island’s greatest luxury is its unfiltered authenticity. What sets Leros apart is the genuine connection visitors can form with locals, the absence of mass tourism, the immediacy of unspoiled nature, and the villages that remain free from sprawling commercial zones. There are no black vans shuttling tour groups back and forth all day, and it’s rare to find yourself waiting for a table at dinner. There are no mega-resorts blanketing the hillsides.

Instead, a gentle, slow-paced form of tourism has begun to emerge more confidently in recent years – especially since the island began to move beyond its association with the psychiatric hospital.

Whether or not Leros will embrace its layered and often uncomfortable history – integrating both its light and shadow into a fuller identity – remains to be seen. In the meantime, Heidi will go on learning the rhythms of the Aegean sun, camera in hand, still chasing that perfect shot.

Crithoni’s Paradise (Crithoni, Tel. (+30) 22470.251.20) The largest hotel on the island offers a wide range of accommodations, from standard doubles and family rooms to suites and maisonettes. All units are fully equipped, and the property includes a restaurant and a pool bar.

Alidian Bay Suites (Alinda Beach, Tel. (+30) 694.291.9177) Located at the quiet end of popular Alinda Beach, this property features modern suites and apartments, most with sea views. It also offers a restaurant and swimming pool.

Archontiko Angelou (Alinda, Tel. (+30) 22470.227.49) Housed in a traditional mansion built in 1895 as a summer retreat, this charming guesthouse offers rooms and suites with wrought-iron beds, wooden floors, and a colorful garden perfect for breakfast or a relaxing coffee break.

Tony’s Beach Hotel (Vromolithos, Tel. (+30) 22470.247.42) Set right on Vromolithos Beach, this family-friendly hotel offers spacious and well-appointed studios – ideal for travelers with children.

Bianco Hotel (Lakki, Tel. (+30) 22470.224.60) Centrally located in Lakki, this modern and recently renovated hotel features simple, stylish rooms in a minimalist aesthetic. Some units offer scenic views.

Phlea Farmstay (Alinda, Tel. (+30) 697.923.1520) For a unique stay, this farm offers studios set among fragrant orange and mandarin groves. Each unit includes a fully equipped kitchen, making them ideal for longer stays.

Trechantiri (Xirokampos, Tel. (+30) 22470.234.08) You’re likely to see more locals than tourists here – always a good sign. Expect the day’s catch grilled over open flame, along with crisp calamari, fork-tender octopus, and tiny fried fish fresh from the pan.

Mylos by the Sea (Agia Marina, Tel. (+30) 22470.248.94) Located right by the sea and a restored old windmill, this restaurant owes its growing reputation to the creative vision of chef Marios Koutsounaris, who runs it with his brother Giorgos. Expect imaginative dishes such as calamari carbonara with smoked swordfish instead of bacon, asparagus with smoked eel, and handmade pasta filled with shrimp and fresh herbs.

Serza (Merikia, Tel. (+30) 693.159.0794) This restaurant serves a small, seasonal menu that changes daily. Highlights might include marinated sea bass with zucchini and capers, a twisted onion pie with spicy cheese dip, grilled parrotfish with avgolemono sauce, and wild sea greens sautéed with olive oil and lemon.

Da Michele (Panteli, Tel. (+30) 22470.222.44) A beloved pizzeria serving thin-crust Italian-style pizzas made with just a handful of high-quality ingredients. Expect only a few salads on the side and no pasta.

Yparcho (Platanos, Tel. (+30) 22470.222.09) A classic local grill house known for its wrapped souvlaki. The house special? A burger patty stuffed into warm bread with a fried egg, tomato, and onion. You’ll also find all the staples: gyro, skewers, and country-style sausage.

Sip it (Lakki, Tel. (+30) 22470.253.97) A beloved meeting spot in the heart of Lakki. Open from early in the morning until late in the afternoon, it’s known for its consistently good coffee and relaxed atmosphere.

Savana (Panteli, Tel. (+30) 698.580.4821) Right by the sea, this easygoing beach bar is known for its well-crafted cocktails and laid-back vibe – the perfect spot to end your day.

Harris (Myloi, Tel. (+30) 693.682.8615) Housed in a restored windmill just below the island’s castle, this atmospheric bar serves cocktails, cold beer, and drinks, accompanied by a short menu of snacks. The view over Panteli Bay is stunning, especially at sunset.

Hydrovius Dive Center (Krithoni, Tel. (+30) 22470.260.25) Run by veteran diver Kostas Kouvas, one of the most experienced professionals in Greece, this center offers guided dives to nine World War II wrecks and sea caves. With some luck, you will come across fish colonies and even dolphins. While the wreck dives are best suited to advanced divers, beginners can also safely enjoy an introductory dive experience.

Caserma of Herbs (Koulouki, Tel. (+30) 22470.280.15, visits by appointment) This herb farm overlooking Lakki Bay is a social initiative led by the Mental Health Cooperative of the Dodecanese. Visitors can explore the gardens, learn about aromatic herbs, and purchase locally produced, all-natural honey.

War Museum – Merikia Tunnel (Merikia, Lakki, Tel. (+30) 22470.221.09, open daily 09:30-13:30, entrance €3) Set inside a restored Italian-built tunnel, this museum displays uniforms, maps, radios, machine guns, and military models. The exhibits are brought to life by ambient sound recordings that recreate the battles once fought here.

Deposito di Guerra (Leros, Tel. (+30) 697.264.5159, visits by appointment, suggested donation €5) The private collection of Ioannis Paraponiaris features military artifacts unearthed across the island – weapons, uniforms, bullets, and even landmines. An essential stop for history buffs.

Leros Bikes (Lakki, Tel. (+30) 694.292.8276) Explore the island on two wheels. Standard and electric bikes are available, and routes can be customized to suit all fitness levels. Owner Fanouris Kontogiorgakis also leads tree-planting initiatives and cycling lessons for local children.

Leros Theater Group (Tel. (+30) 694.438.3920, 693.740.9859) The island’s vibrant theater troupe stages original productions throughout the summer. Check their social media for performance dates and venues.

Leros boasts a wealth of beaches – both large and small. Alinda, Panteli, Vromolithos, and Dio Liskaria are serviced and easy to access. For quieter, more secluded spots with crystal-clear waters and no amenities, seek out Kokkina, Aghia Kioura, or the aptly named Kryfos (“Hidden”).

Discover festivals, beaches, food, and hidden...

Experience Spetses in its most enchanting...

More and more Europeans retire to...

On the Greek island of Hydra,...