VERGINA’S RESTLESS ROYALTY

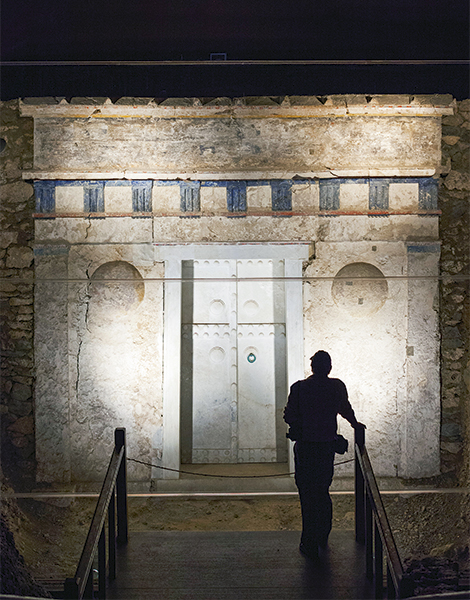

In one-day journeys out from Thessaloniki, visitors can discover important nearby sites. Vergina (Aigai), the original capital of ancient Macedonia, was eclipsed by Pella around the end of the 5th century BC and became a royal summer retreat, an elite burial ground and the scene of Philip II’s assassination in 336 BC – when the king was slain by a disgruntled bodyguard/lover in the old palace’s small theater. Currently, the palace is closed for conservation, but one can visit other parts of the site: most notably the fenced-off theater and the Macedonian royal tombs in the Great Tumulus. Manolis Andronikos’ discovery of these elegant tombs and their rich furnishings in 1977 – one of which contained the remains of Philip II – has had much the same impact on Greek archaeology and history as Heinrich Schliemann’s formative late-19th-century revelations concerning the Bronze-Age kings of Mycenae.

© Museum of the Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina

Today, however, a great controversy swirls around Vergina, with respect to the exact location of Philip II’s burial, which – in conjunction with the remarkable but enigmatic recent finds from Amphipolis (see below) – has invigorated northern Greek archaeology and demonstrated that great mysteries from the ancient past still remain to be solved. Although Andronikos originally claimed, based on initial, still-to-be-fully-analyzed material evidence, that Philip was interred in Tomb II, a host of new evidence from now-completed studies of Tomb II’s black-glazed pottery, silver vessels, architecture, wall painting and burial goods all point to the need for revised interpretations. The repeated, conflicting examinations of cremated human remains have been inconclusive.

All in all, it now seems highly likely that Tomb II and its contents date to the last quarter of the 4th century BC, after Philip II’s death and interment (probably in adjacent Tomb I), and that some other royal personage was buried in Tomb II (perhaps Philip III Arrhidaios), along with official and personal objects that once belonged to Alexander the Great. These included his silver diadem, gold-and-wood scepter and personal armor, consisting especially of a distinctive iron, battle-damaged helmet and a chryselephantine shield depicting Achilles slaying the Amazon queen Penthesilea.

This mythological subject had no significance for Phillip II, but was appropriate to Alexander, who prided himself on being a descendant of Achilles and was an ardent admirer of the hero. The proposed re-dating of Vergina’s Tomb II falls within the 350-310 BC time span previously accepted by Andronikos, who himself acknowledged in 1984: “Though it falls to me to have the first word, I am certainly not the person who will have the last.” The museum at Vergina ranks among the most intriguing, visually impressive public exhibitions in Greece.

© Archaeological Museum of Pella

PELLA RE-EMERGES FROM THE SILT

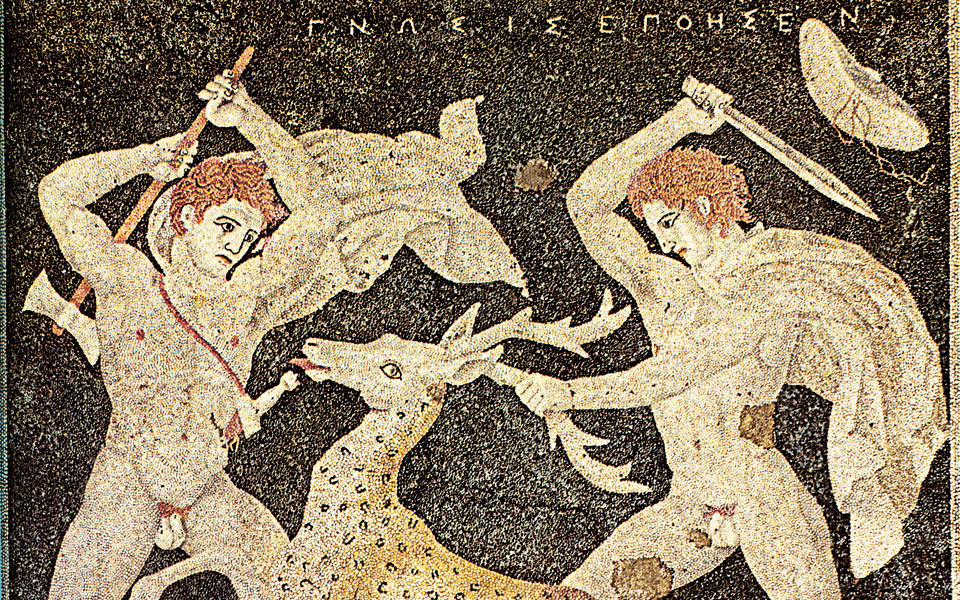

Ancient Pella, now landlocked among agricultural fields, was the region’s major seaport in the late 5th and 4th centuries BC. Its affluent, colonnaded courtyard houses, furnished with exquisite, mythologically-themed mosaics by master craftsmen such as Gnosis, were arranged according to a gridded city-block plan and served by strikingly modern water and sewer systems. Both Philip II and Alexander the Great were born at Pella (382, 356 BC, respectively). During its heyday, the city became a powerful, celebrated center of politics and culture, whose royal court attracted leading figures in the arts and sciences, including Euripides, Aristotle, the painter Zeuxis and the Theban musician Timotheus.

© Archaeological Museum of Pella

Fortified with defensive walls five meters thick, Pella’s cityscape featured numerous sanctuaries for the worship of deities including Dionysus, Aphrodite, Athena and Darron, a local healing god. At the city’s heart was an enormous agora, lined with two-storied shops; its palace stood on a low hill to the north. Baths, workshops and extensive extramural cemeteries have also been revealed. After 315 BC, when Pella was superseded by Thessaloniki, its coastal environment had already begun to deteriorate, thanks to increasingly marshy, unhealthy conditions prompted by the expanding deltas of adjacent rivers.

Nowadays, Pella once again appears to be a hive of activity, with archaeological excavation and restoration projects evident throughout the site. The opening of a new, state-of-the-art museum in 2009 seems to have launched a fresh era at Pella. The museum’s creative, thematically arranged displays illuminate the public, private and commercial life of ancient Pellans, with particular emphasis on the worlds of women and men, children’s toys, bronze sculpture, painted pottery, writing and the city’s far-reaching trade connections.

© Shutterstock

WELL-WATERED DION, AT THE FEET OF OLYMPOS

Now a pleasant archaeological park with tree-shaded paths and partly flooded ancient temples, Dion was the most important religious sanctuary in ancient Macedonia, dedicated primarily to Olympian Zeus. This was a mythical spot, believed to be the birthplace of Macedon, Zeus’ son and the Macedonians’ eponymous forebear. Artemis, Aphrodite, Dionysus, Demeter and Isis also had shrines here.

© VisualHellas

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

With its strategic frontier location, Dion served as a key, stoutly walled military base – a favorite haunt of Alexander, where he hosted lavish celebrations prior to his Asian campaign and, in 334 BC, commissioned a Lysippan sculptural monument to commemorate his fallen companions after the Battle of Granicus. Despite a devastating Aetolian attack in 219 BC, Dion quickly recovered, reaching new heights as a prosperous, much admired city and subsequently a long-flourishing Roman colony (founded by Octavius), with affluent villas, large public baths, theaters, basilicas and stone-paved streets.

The luxury of private life at Roman Dion is revealed by the so-called Villa of Dionysus, with its elaborate baths, multicolored mosaics, classically-inspired sculptures and nearly 100 sq m dining hall. Dion’s many graceful statues now reside in the site’s museum, where visitors will also discover the earliest known example (1st century BC) of a hydraulis – an air-driven musical instrument with bronze pipes that represents the forerunner of the modern church organ. Outside, one can stroll down ancient avenues, near the Vaphyras River, or take in a musical or dramatic performance at the city’s 2,500-year-old theater.