It is a scorching hot, midsummer’s day up in Ano Mera and, standing atop a brown, rocky formation, typical of the Mykonian landscape, Dimitris Mantikas, an architect who has built more than 200 houses here since 1981, is left to the inspiration brought in by the strong Meltemi wind whipping the hillside. He ponders upon the challenges of the deteriorating ground and the clusters of rocks that need to be preserved. He has to take everything into account: the strong winds, the ever-changing course of the sun, the durability of his designs, the environmental impact of the structure and, of course, the view from the finished edifice.

In front of him lay different but very similar white blocks, all typical samples of Mykonian architecture. For some, these are simple forms offering practical benefits. For others, they are a means of showing off wealth. But for the architects and designers that we meet, these materials are the physical embodiment of a love affair, with all the turmoil and excitement that pathos usually brings along with it.

“What they used to say was, ‘A house just enough to fit in, a field just as far as you can see’.”

© Courtesy Bc Estudio Architects

Like Tetris blocks

The colorful crowds that flock the streets of Matoyianni every summer probably don’t know that once upon a time, long ago, the island was filled with castles, the remains of which can still be found in places like Lino and Portes. From this very well organized defense system that protected the island from pirates and thieves to the huge villas with the crisp swimming pools that are found today on every little hillside, there have been centuries of evolution and transformation, always adding new elements to what we call today traditional character. And all of these changes were driven by the needs of the day.

The little houses were built one atop the other and the streets were made as narrow as possible in an attempt to close up the town against the pirates. The houses were small due to the scarcity of basic building materials and their shape and color were in reaction to unique weather conditions. Square formations and white colors protect from strong winds and the melting heat.

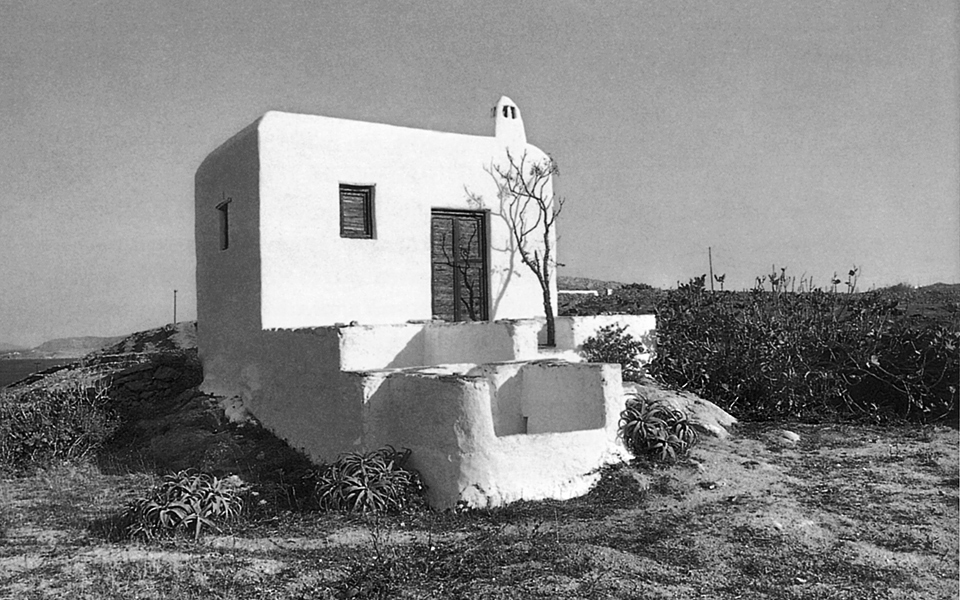

All this takes place in Chora, the central stage of the island. Ion Stavropoulos, an architect who has known the island since the seventies, also talks about the simple, plain cottages in rural Mykonos: “These were bright examples of the so called ‘additive architecture’, little gems of anonymous folk creativity, symbols of another type of civilization, created by poverty and inventiveness, edifices that the modernist architect Aris Konstantinidis called ‘god-built’”, he says.

Basic living dwellings were formed by cell-like rooms creating “wings” around shaded little patios. A corral for the animals, a wood-fired oven, a winepress, a water cistern, a well, and, in many cases, a small chapel would complete the farmhouse or “chorio”, a word used euphemistically for these farmhouses scattered in the rural areas, since it actually means “village” in Greek.

“This organic and shabby creation of unities ended up becoming a masterpiece of unique character”, says architect Nikiforos Fokas, while Apostolos Nazos, a born and bred Mykonian architect actively involved in strengthening the protection afforded by the local urban planning, adds: “The people who created these masterpieces were very much aware of the concept of space. Today, we are left speechless when we think of their simplicity and moderation. Every little cube is placed in the right part of the field that surrounds it, correctly oriented, and of a size barely fitting the soul of a man. What they used to say was, ‘A house just enough to fit in, a field just as far as you can see’”.

“Once there merely to satisfy the basic needs of the dwellers, the house gradually became a vessel to serve luxurious holidays and become a tell sign of the owner’s wealth” Ion Stavropoulos, architect.”

A sculptural masterpiece

Round rocks, dry earth patches and scattered little whitewashed chapels create a dreamscape that, since 2005, has been protected by law; the island itself is legally classified as one of distinctive, natural beauty. When the sculptor and interior designer Deborah French first set foot on Mykonos in 1978, she instantly fell in love with the island. She kept coming back almost every year, until finally moving here in 1985. “Though one could argue that other places had some of these qualities, Mykonos is where I found them,” she says. “The architecture, the sculptural quality of the structures that, being white, stand out so well, allowing the eye to see the shapes as a union and to follow the undulation of the surfaces…

Other Cycladic islands had this, but none quite as perfectly.” So she decided to set up her home here, calling it “Re-inventing Mykonos”: “The original architecture of the island was my general inspiration but I took much of it from a small old farmhouse where I’d had spent my summers. It was so simple yet very alive, because of all the movements of its surface and the simple rustic details. Being a sculptor I could fully appreciate its beauty and uniqueness.”

“’The architecture, the sculptural quality of the structures that, being white, stand out so well, allowing the eye to see the shapes as a union and to follow the undulation of the surfaces…’”

© From Mykonos, a Photographic Memento (1885-1985) by Panayiotis Kousathanas

© From “Mykonos, a Photographic Memento, Volume II, 1951-1985, by Panayiotis Kousathanas.

The firm law of the land

It is safe to say that, having worked here for 35 years, Dimitris Mantikas knows the island like the back of his hand. “The reasoning of nature, of the landscape here, is much more powerful than that of the builders who tried to impose their vision on it”, he says. Javier Barba, a Spaniard who has built more than six houses here since 1997, finds his calling to be the integration of each project into the landscape: “We work the architecture from the land, with the land, adjusting to the natural pre-existing conditions. The landscape conditions you, inspires you and gives you guidelines to work on,” he says.

The wind, too, is a force to be reckoned with on Mykonos. The tough one, the Meltemi, comes from the north. The Mykonians situated their houses with their “backs” turned to the north, to shield from the wind. “On a windy day in the old houses, you could stand on the front veranda and be completely protected. This simple intelligence has been lost to those of us who are disconnected with nature and the concept of bending to it for our ultimate advantage” says Deborah French. Nikiforos Fokas believes in the elements as well. “The landscape, the climate and the strong Mykonian tradition can only bring inspiration,” he says. That inspiration, however, may come at a price.

Looking back on his first ever commission on the island, Apostolos Nazos remembers he was frozen, unable to use everything he had been taught. It was impossible to intervene in what to him was – and still is – magical scenery. Thankfully, the law has worked to the advantage of Mykonos. For her house, Deborah French had to get special permission that allowed her not to paint it white. At that time, only the animal shelters were left unpainted. “I saw that a large white house up on the hill would look ostentatious and detract from its surroundings. But built from rock, the residence blends in and almost disappears into the hill. A few years after the house was built, a rule went into effect that houses up on the hills should not be painted white. Someone got the point!”

It was, in fact, Dimitris Mantikas who brought the revised study of her house to the architectural committee, and he was also the first architect to design and establish the double walls that resembled the shapes of old farmhouses, starting a trend back in the mid-’80s. “The buildings blend well with the environment and the land has been respected,” he says. “So, if you want to talk about eco-friendly architecture, it is not always about the use of double windows or putting solar or aeolic energy to use. The way the island has been built is totally eco-friendly. Not to mention that traditionally the roofs were insulated with sand and seaweed!’’

“The Mykonians situated their houses with their “backs” turned to the north, to shield from the wind. ”

The inevitable «facelift»

Ion Stavropoulos talks about a violent rise in construction that started in the mid-’80s and has changed the landscape: “From being something to satisfy the basic needs of the dwellers, the house gradually became a vessel for luxurious vacation and a sign of the owner’s wealth. Contemporary materials, often imported, allowed for buildings that wouldn’t have been built by the architects of old,” he says. Deborah French adds: “The town of Mykonos was transformed in a matter of a few years from one whose streets were pristinely clean and white-washed with lime wash, bathed in soft, natural light, to one where, once high-end retailers descended, the lights became garish and the streets dirty, painted once a year at best, and with latex or enamel paint. It is a good example of how insensitivity and ignorance have eaten away at what was once so special about Mykonos.”

Wealth, well hidden

Skyrocketing land prices and high demand for real estate have turned Mykonos into a unique case study. According to Ion Stavropoulos, architects are often called in to design structures on secluded tracts of land, chosen solely for the purpose of offering its owner the privacy he seeks. This seclusion poses numerous challenges, including not having access to basic infrastructure, such as sewage systems and water supply.

Nikiforos Fokas believes the island has been going through a nouveau-riche phase for a long time, but Dimitris Mantikas is more optimistic: “Although there has been an effort to create a golden facade through Mykonian architecture, in general the buildings haven’t lost their traditional shape thanks to the urban planning laws. The only place left for showing off is the inside of the houses.” According to a spokesperson from the architectural design firm Zege, “it is easy to assume that Mykonos is an island of loud manifestations of wealth. But in architectural terms, there is a constant struggle to keep our traditional Cycladic building principles, devoid of excess and modernity.”

“According to Ion Stavropoulos, architects are often called in to design structures on secluded tracts of land, chosen solely for the purpose of offering its owner the privacy he seeks. ”