1. The Sordid Murder of King Philip

Macedonia’s King Philip II, father of Alexander the Great, is remembered for astonishing military and political feats – even becoming master of Athens – but it may be his outrageous personal character, sacrilegious conduct and shocking death that continue to intrigue us the most.

As well as a battle-scarred warrior, a polygamist and a famous hedonist, he was also said to be a notorious seducer of both women and young men, and he ultimately fell victim to a disgruntled lover.

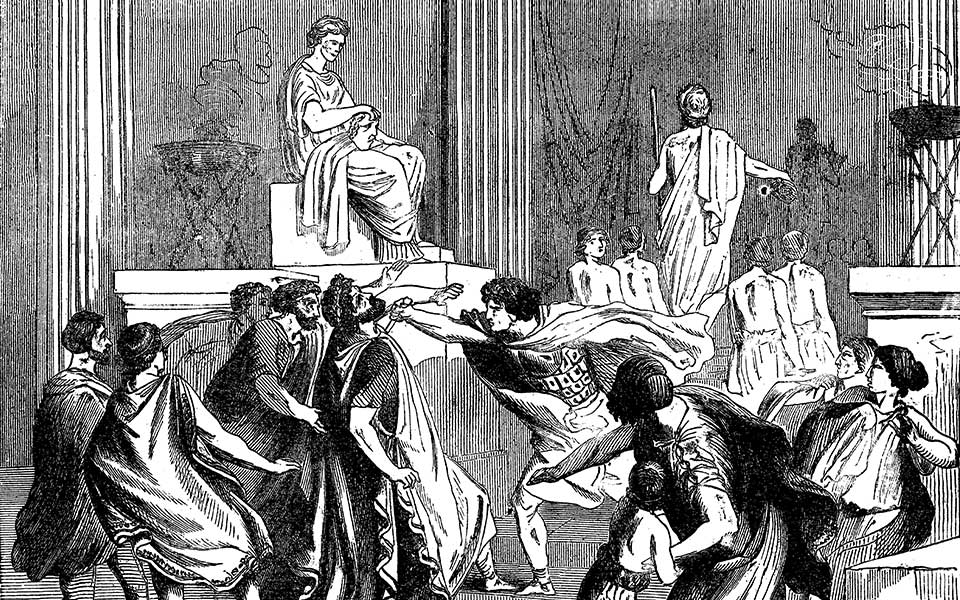

Diodorus Siculus reports Philip was murdered in 336 BC as he entered the theater at Aigai (Vergina), irreverently parading his own sculpture among sacred images of the Olympian gods. His attacker, Pausanias of Orestis, who had recently been “disrespected” by a gang of drunken muleteers by order of Attalus, Philip’s right-hand general, vengefully stalked and stabbed the king.

After an inglorious death, Philip received a glorious burial at Aigai.

© visualhellas.gr

2. Alexander: The Star that Burned Brightest

No star shines brighter in the rich constellation of Macedonia’s history than Alexander the Great, who conquered the East and laid the foundations for the Hellenistic world.

As a brilliant strategist and motivator of men, he pushed the bounds of empire and convention, leaving a legacy of Greek culture and accomplishment still detectable in distant corners of Asia.

Yet, like his father, he lived fast, drank too much wine, enjoyed indiscriminate sex and placed himself on a par with the gods.

After conquering Egypt, Alexander became the new pharaoh, a figure viewed as divine. In 331 BC, he also traveled to the sacred oasis of Siwah, where he was declared the son of Zeus Ammon. His sudden death in 323 BC continues to be debated, attributed variously to disease or overindulgence – but perhaps abetted by a rising resentment among his own men, or even the envious gods.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

3. A HORRIBLE FINAL ACT

The great playwright Euripides was born on the island of Salamina in 480 BC, on the very day that the Greeks destroyed the Persian fleet in the historic battle that took place just off its shores.

He had a tumultuous family life, and as for his death, fate dealt him a strange hand. Sometime around 409 BC, Euripides moved from Athens to Macedonia. Archelaus I of Macedon had invited him to Pella, where the king had gathered many notable artists in his court. Tradition has it that, while there, Euripides intervened to save some hunters from severe punishment for having killed a hunting dog from the royal pack.

In an ironic twist, it was the king’s hunting dogs, starved before a hunt, that killed Euripides, mauling him to death in a forest not far from Pella in 406 BC. While some of his Athenian contemporaries felt this a fitting end for an impious man, the Macedonians did not and showed their love

by burying him as one of their own.

© visualhellas.gr

4. Error 404: Sea Not Found

The founding of the city of Thessaloniki, by Cassander sometime around 315 BC, was a reaction to the silting in of the Thermaic Gulf’s former major port city, Pella, which once lay on the coast.

As the alluvium from nearby rivers choked Pella’s port facilities and natural inlet connecting it to the sea, the shoreline gradually accreted outward, leaving Pella, once the palatial headquarters of Macedonian kings (including Philip II and Alexander the Great) high and dry; today, it sits in the midst of vast agricultural fields.

This developing environmental calamity may have been exploited by Cassander as one justification for building his own capital, named for his wife Thessaloniki, Alexander’s sister, further to the east.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

5. The Mystery Tomb Fit for a King

At Amphipolis, archaeologists continue probing the enormous ancient tomb discovered in 2012 on Kasta Hill. But a great mystery remains. Who was buried there? Could it be Alexander the Great, his Persian wife Roxana, an esteemed Macedonian officer or a Roman VIP?

Amphipolis was a major fortified city, where, following Alexander’s death, Roxana and her teenage son, Alexander IV, were imprisoned by Cassander. The Kasta crypt certainly appears to be a Macedonian tomb of the 4th c. BC, and is surrounded by a huge marble wall 158m in diameter – the largest such funerary monument in Greece.

However, King Alexander was buried in Egypt; Prince Alexander at Aigai/Vergina; and Queen Roxana, poisoned at Amphipolis in 309 BC, was “undeserving” of such an imposing memorial.

Clearly, an important personage remains to be identified. Or was Kasta monumentalized by later hero-worshiping Hellenistic or Roman authorities, with a similar (mistaken?) notion that some great figure lay in the elegant antique tomb?

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

6. Massacre or Mistake?

The Roman emperor Theodosius I once ordered the massacre of thousands of his own subjects in Thessaloniki. Or did he?

In AD 390, after a popular charioteer was arrested, a riot broke out and a local military commander was killed. Legend holds that Theodosius decided to punish the city, ordering the deliberate slaughter of as many as 7,000 spectators who were in the hippodrome watching the races.

However, a recent study by historian Stanislav Dolezal (2014) suggests the deaths resulted from panicky troops sent in to make sweeping arrests among the citizenry, regardless of guilt or innocence. After the crowd became unruly, the hippodrome was violently cleared, with great but unintended loss of life.

© Shutterstock

7. Flushed with Success

The hygiene-conscious Romans had “flushing” toilets. At Philippi, you’ll find a rare example of a late Roman/early Christian public latrine, commonly called “the Vespasian,” after the emperor that levied a urine tax on cloth makers and other businessmen who profited from the use or sale of urine (needed for processing fibers).

Beneath the stone bench, equipped with ergonomically designed holes that accommodated the male anatomy, a drainage channel led away to a central sewer. After a visitor “did his business” and cleansed himself with a sponge attached to a stick, the drain could be flushed with water by attendants, keeping everything odor-free and tidy.

© Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation

8. if these walls could talk

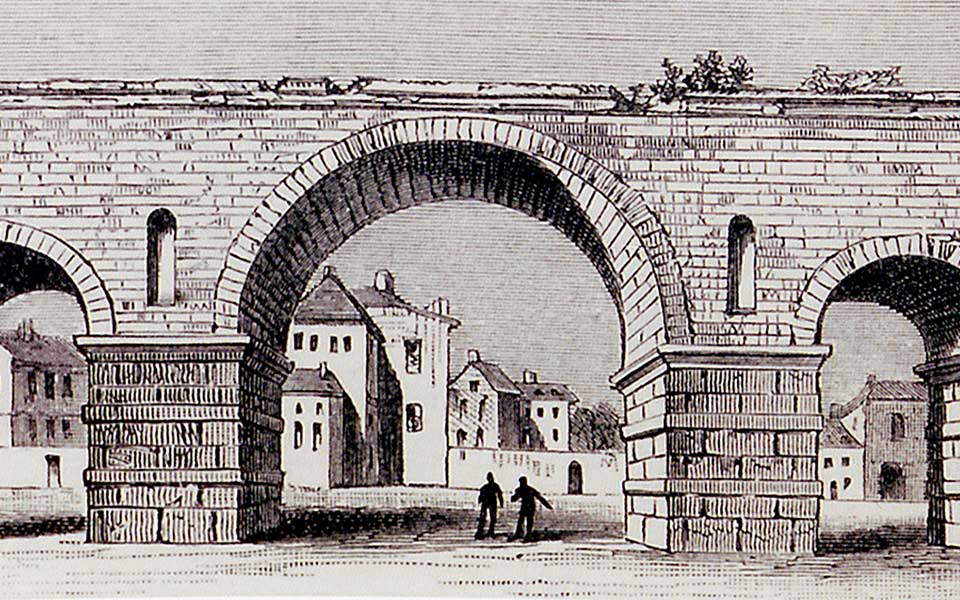

Strolling along Dimitriou Gounari Street, we might forget we are passing through the city’s own “Versailles” – a massive palace complex of the Roman emperor Galerius, who ruled AD 305-311.

The luxury of this imperial headquarters is apparent in the marble-veneered “Octagon,” an audience hall or throne room just inside a vestibule, peristyle and sea gate – today hundreds of meters inland. The complex had two arches: the “Small Arch of Galerius” near the Octagon (now in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki) and the main Arch of Galerius at its northern end.

Later, Constantine the Great finished the Octagon and may have founded the massive domed Rotunda with its magnificent wall mosaics, which eventually became Thessaloniki’s first Christian church.

Lurking behind this opulence is a dark history, however, as Galerius was responsible for the martyrdom of Saint Demetrius, while the palace’s hippodrome is said to have been the site of a notorious slaughter of citizens under Theodosius I.

© Sakis Gioumpasis

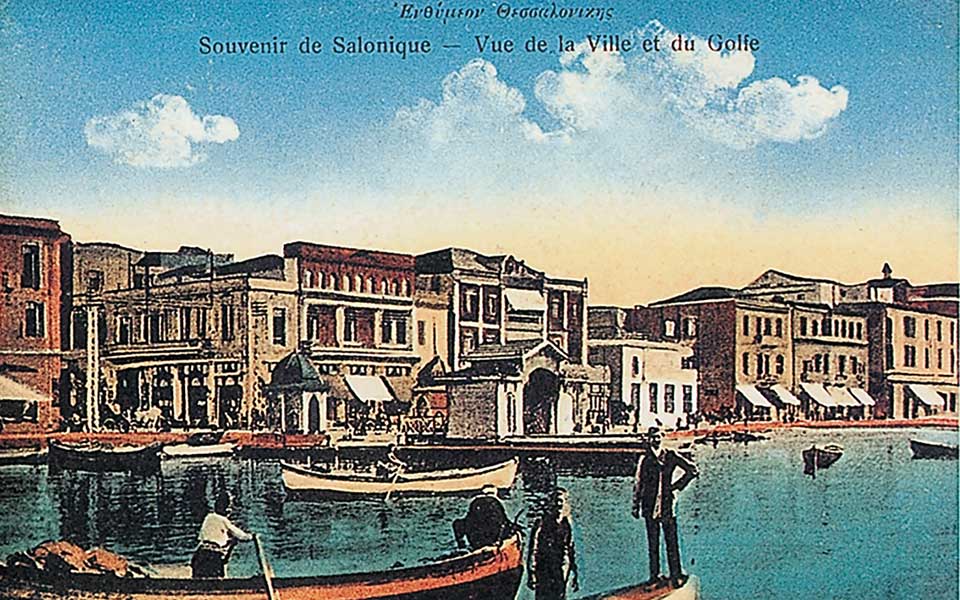

9. The Original Melting Pot

Thessaloniki, through its ancient and medieval history, has been many things: imperial capital, commercial and cultural crossroads, strategic military base, East-West gateway, European melting pot and a not-so-peripheral city, frequently on the verge of outshining the major centers of the day, be they Athens, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Istanbul or Athens again.

Here, the proverbial many threads in life’s rich tapestry were on full display, occasionally rent by tragedy and human suffering, but ever enduring. The extraordinary mix of peoples crowding inside Thessaloniki’s ancient city walls came from all walks of life and occupations – from native Macedonians, Greeks and Italians to Slavs, Franks and Turks. The streets teemed with Christians, Muslims, Spanish Jews, Crusaders, Janissaries, merchants and emperors.

The Apostle Paul visited, Constantine the Great made Thessaloniki Byzantium’s second city and the burgeoning Jewish community after 1492 made it the leading center of Jewish culture outside the Holy Land. Ottoman society and influence also thrived, with Thessaloniki becoming a major Balkan Janissary base and the birthplace of Kemal Ataturk, founder of modern Turkey.

Today’s Thessaloniki draws on its unique cultural past, continuing to be a far-reaching regional capital on the Thermaic Gulf.

10. Christian before it was cool

Nothing says “Thessaloniki!” like the city’s extraordinary Christian churches, some dating from as far back as earliest Byzantine times when the Romans were still transitioning to Christianity.

Today, many of Thessaloniki’s churches remain dynamic centers of an enduring faith, led by the Church of Aghios Dimitrios, dedicated to the city’s early-4th-c. patron saint, now an impressively restored survivor of the Thessaloniki’s 1917 conflagration.

But it’s the smaller chapels, time-bitten and resilient, frequently hidden in the twisting narrow streets of the timeless Ano Polis (Upper Town), which can best transport you back into the mists and spiritualism of the Byzantine World. Every domed apse and frescoed or tessellated wall seems to have a story of survival, revelation and resurrection formed through centuries of invasions, conversions and fires.

The humble Church of Hosios David is missing a corner – indeed, its entire monastery – but its primary mosaic of a beardless Christ, long hidden beneath Ottoman whitewash, dates to the 5th/6th centuries AD.

The Vlatadon Monastery’s frescoes (14th c.) are considered the finest preserved examples of “Macedonian school” painting. The church was built by two Cretan brothers, cloth merchants, who became monks.

The Church of Holy Apostles’ intricate brickwork is extraordinary, while its paintings and mosaics are masterpieces of the Paleologue era (14th-15th cents.) – also later whitewashed, now beautifully cleaned and conserved.