“We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.” –T. S. Eliot

Contrary to what is commonly believed, Kastellorizo’s economic and social decline did not begin and end with the island’s cruel devastation during the Second World War. This heartbreaking final chapter, which included fierce German bombardment, was in fact more in the nature of a coup de grâce for a proudly Greek island that had already withstood economic calamity from as early as the last two decades of the 19th century.

Kastellorizo’s story is an extraordinary one precisely because it does not fit neatly within the traditional Dodecanese island narrative – and yet it remains a quintessentially Greek story. A potent combination of local Hellenic zeal, tightening Ottoman rule, strategic worth coupled with cultural isolation and various accidents of history produced a series of events peculiar to the island. These included the creation of unbridled wealth in the middle years of the 19th century, a local revolt against the Turks in 1913, a short period of frenzied de facto Greek rule, and then successive French, Italian and British occupation, until Kastellorizo’s long-awaited and triumphant de jure union with Greece in 1948.

This cascade of events, punctuated by cruel bombardments in both wars and a devastating earthquake in 1926, were to produce wave upon wave of emigration from the island from as early as the 1880s up until the aftermath of the Second World War.

The first brave adventurers departing the island were, typically, young males seeking new opportunities in territories as diverse as France, the Belgian Congo, Brazil, the East Coast and southern states of America, and, in greatest numbers, Australia. And gradually, as more and more relocated over time, the epicenter of the Kastellorizian “experience” shifted from the island itself to a distant, far larger island continent to which the island’s memorial and material heritage was progressively transplanted.

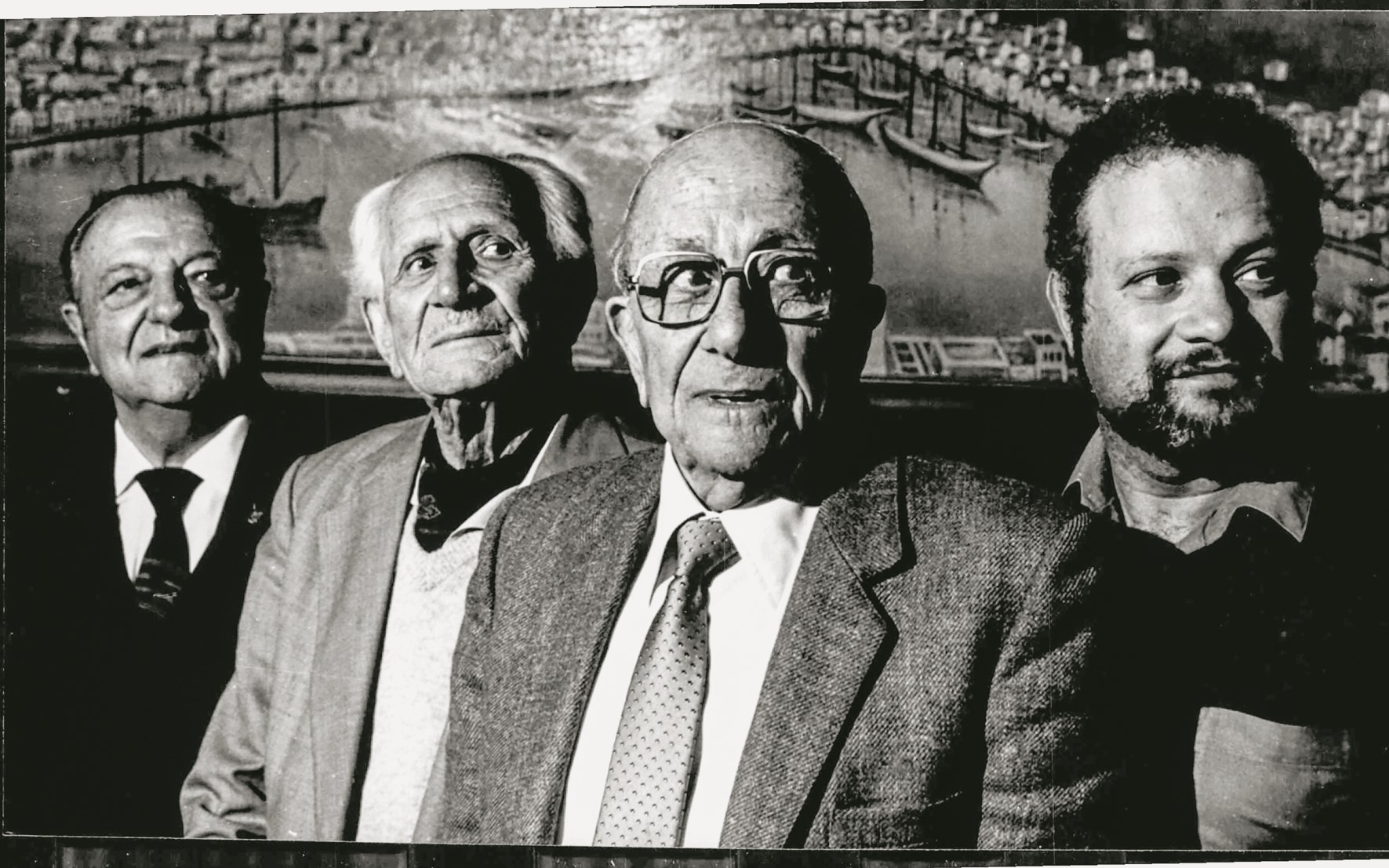

© Getty Images / Ideal Images

Today, it is estimated that over 80,000 Australians claim some familial link to Kastellorizo, an island that, at its zenith, supported a population of no more than 10,000. And while smaller Kastellorizian communities flourished for many decades in places like New York and Florianopolis, Brazil, there is little doubt that, today, the island’s heart beats loudest in Australian cities like Perth, Darwin, Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide.

In these multicultural urban centers, Kastellorizian family names like Paspaley, Kailis, Liveris, Michael, Harmanis, Zempilas, Mangos and Bolkus are not only synonymous with success, but they’re deeply embedded into the modern Australian mosaic, too. And connecting them all is a nostalgic – some might say tenacious – attachment to a 10-square kilometer limestone rock in the eastern Mediterranean that has produced a diaspora community whose yearning for their legacy is all-pervasive. Adorning their living rooms one will commonly find the ubiquitous black and white letterbox-cropped image of Kastellorizo’s harbor crammed to capacity with two and three-masted brigs and barks. The fact that the photograph dates from the last decade of the 19th century, three or even four generations back in time, does not lessen the image’s force.

This is what Kastellorizo represents for these proud diaspora Greeks, even if such prosperity was already but a memory a century ago. Nevertheless, gazing at the image will routinely evoke treasured memories of a grandfather’s maritime tales or a grandmother’s delicate embroidery or ornate bridal costume.

© Getty Images / Ideal Image

Aside from its indigenous past, Australia was, to a large degree, a blank canvas for the early Greek migrants who arrived not only from Kastellorizo but also from Ithaki, Florina and Kythera. This enabled them to speedily make their mark in their chosen destination. Associations were formed and churches were built (the oldest Greek Orthodox church in Australia is that of Aghia Triadha, or the Holy Trinity, in Sydney, which was consecrated in 1898, just prior to the consecration of Evangelismos in Melbourne in 1899).

Needless to say, such initiatives were vital to the maintenance of cultural and religious identity in a new land. But to their fellow Greeks, the Kastellorizians (or “Kazzies” as they came to be known) seemed to project an unfamiliar sense of “otherness.” Occasionally surprised by the Kazzies’ eastern brand of “Greekness” (a quality they shared with many other Asia Minor Greeks), some Greeks could not handle the paradox of labeling a fellow Greek from another place as a xenos (foreigner).

This, and other peculiarities, led to some occasional tensions, but over time such differences dissolved and new non-regional associations were formed to cater to a broader pan-Hellenic audience. And still, the passion of the Kazzies for a romanticized “return” to their island gained traction, long after their relatively seamless integration into broader Australian society. The more time that passed, the greater was the expectation.

Indeed, the more “Australianized” the Kazzies seemed to become, the stronger was their yearning for the rediscovery of their “lost” island. Encouraged by Australia’s policies promoting multiculturalism, the children, grandchildren and even great-grandchildren of early pioneers started making their own “pilgrimages” to see for themselves where it had all begun. Long-abandoned properties were reclaimed, neoclassical homes were slowly restored and Greek identity was proudly rediscovered. Genealogical trees stretching back to the 19th century were painstakingly researched and assembled, while old photographs were retrieved from kaseles (chests), reframed and displayed again.

© Australian Friends of Kastellorizo, 2018

All of this coincided, of course, with a renaissance of sorts on the island itself, when the azure waters of the easternmost Greek islands became the latest unexplored paradise for itinerant yachtsmen and tourists. On Kastellorizo, new restaurants opened, cafés and bars traded noisily, and the prokimea (waterfront), where over a century earlier merchants and sea captains had walked, became instead a place for sunbathers and revelers. But in the island’s narrow lanes, more private moments of exploration began, as old neighborhoods were rediscovered and oft-told reminiscences at last made sense within their proper context.

Today, one could argue that the Kastellorizian diaspora in Australia is as vibrant as it ever has been, fueled as it is in large part by the vacation experiences of these descendants’ regular sojourns on the island. Admittedly, this is a far cry from the earlier years, when afternoons in clubhouses in Sydney or Perth, surrounded by colorized photographs of a devastated island landscape provided a much-needed connection to the island. But today, clubs and brotherhoods are being reimagined and are slowly but surely redirecting their energies towards valuable cultural efforts that seek to preserve and propagate the legacy that their ancestors transported to a new homeland clear across the globe. And diaspora links to Kastellorizo are being reinforced by charitable organizations like “Friends of Kastellorizo” which refocuses expatriate attention and assistance on the essential needs of the island.

The quotation from T. S. Eliot which opened this piece could not be more appropriate. The diaspora experience of the Greeks of Kastellorizo will only be truly complete when their journey has come full circle for their descendants. It is of lasting credit to our forebears that they undertook that journey in the first place, but it remains our, and our children’s, challenge to complete that circle of exploration and come to “know” our island – and, thereby, Greece – for the first time.

This article first appeared in the print edition of Greece Is Kastellorizo 2020 with the title “A Tale of Cultural Endurance”.