Nestled on a low outcrop overlooking the fertile Argolid plain in the northeast Peloponnese, the citadel of Tiryns is an awe-inspiring site that is often missed off visitors’ itineraries in favor of its more famous sister-site, Mycenae, located 20km to the north.

Renowned since antiquity for its “Cyclopean” walls, an architectural marvel characterized by the use of massive, irregularly shaped limestone blocks that were skilfully interlocked without the aid of mortar, Tiryns stands as a remarkable testament to the advanced engineering skills of the Mycenaeans, a Bronze Age civilization that flourished in Greece from approximately 1600 to 1100 BC.

© Shutterstock

“Tiryns of the Mighty Walls”

The enormous fortification walls of Tiryns were built to protect a large palace complex, an important center of regional power and influence in the Argolid. The citadel’s strategic location overlooking fertile lands and in close proximity to the Argolic Gulf allowed it to control agricultural production and trade routes. At its height in the 13th century BC, Tiryns emerged as one of the most important centers in the Mycenaean world.

Referenced in Homer’s epic poems (c. 8th century BC) as “Tiryns of the mighty walls,” later Greeks marvelled at the sheer size of the site’s defensive perimeter, 750m long, 13m high, and almost 7m thick in places. Many simply didn’t believe the gigantic limestone blocks, some weighting over 10 tons, were put in place by human hands. The most popular tradition in antiquity was that they were erected by the Cyclopes, primordial one-eyed giants that possessed supernatural strength and were master craftsmen – hence the term “Cyclopean masonry.” The Greek traveler and geographer Pausanias, who visited the ruined site in the 2nd century AD, noted that a pair of mules pulling together could not shift even the smaller stones. Whatever their origin, the walls highlight the Mycenaean Greek obsession with defense and strategic control.

Today, the archaeological site of Tiryns, located on the outskirts of the historic coastal city of Nafplio, is seldom visited by large groups of tourists. As such, you’re likely to have the site to yourself, to wander and explore the upper and lower sections of the citadel and the nearby tholos (beehive) tombs. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999, along with the nearby ruins of Mycenae, it is a must for archaeology and literary buffs who want to immerse themselves in a site that is inextricably linked to the Homeric epics and ancient Greece’s “Age of Heroes.”

© Public domain

© Public domain

Palace complex

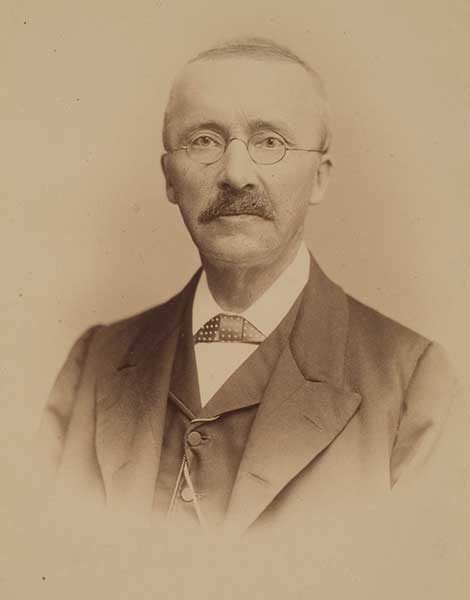

Tiryns has been the subject of multiple excavation campaigns over the years. One of the most significant and influential excavations was carried out in 1884-1885 by Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), a pioneering archaeologist best known for his excavations at Troy and Mycenae.

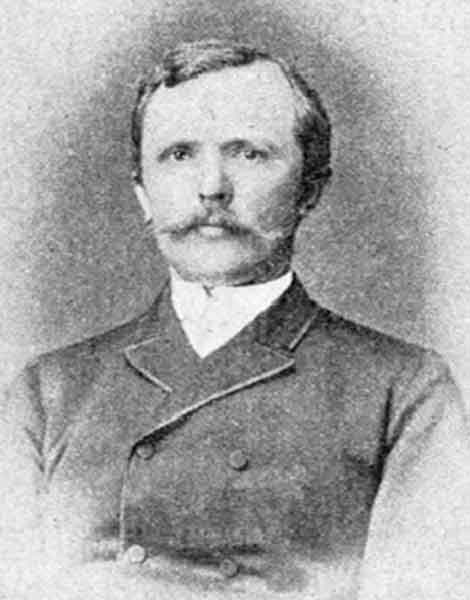

Subsequent excavations by Wilhelm Dörpfeld (1853-1940), a director of the German Archaeological Institute and founder of the German School of Athens, unearthed the full extent of the defensive walls, the site’s monumental gateway, and its labyrinthine complex of courtyards, corridors, and private apartments that make up the upper citadel’s interior.

The latest round of excavations, carried out by the German Institute and the Greek Archaeological Service, took place in the early 1980s.

Inhabited since the Neolithic (“New Stone Age”), 7th-4th millennium BC, Tiryns gradually developed into a flourishing settlement during the Early Bronze Age (Early Helladic, c. 3200-2000 BC). At this time, the site was unfortified but a large circular structure 28m in diameter, made of mud brick and stone, and located at the heart of the settlement, may have served as a grain silo, a place of communal gathering, or the residence of the local chieftain or king.

© Shutterstock

The settlement underwent its greatest growth during the Late Bronze Age (Late Helladic, 1550-1050 BC). The surviving ruins of the Mycenaean-era citadel date to the 14th-12th centuries BC, during which time the renowned Cyclopean walls were erected, as well as a large reception hall known as a “megaron,” with a columned porch and an anteroom (“prodomos”) – the heart of the palace complex.

The layout of the megaron, with its large circular hearth and elevated throne, was the seat of power for the “wanax,” or king, and served as the focal point for social and administrative activities. A complex network of private apartments with baths and drains, radiate outwards from megaron, a characteristic feature of all contemporary palace sites in mainland Greece (inlcuding Thebes and Pylos). These apartments, once decorated with colorful wall frescos, likely served as the residences for members of the royal family.

Inhabitants of the settlement that were not directly linked to the day-to-day administrative activities of the palace lived in the area of the lower citadel, alongside workshops and places of cultic activity. Two tholos tombs with corbelled domes (gradually projecting, overlaying blocks), located 1km away from the main site, indicate the presence of a royal cemetery.

© Shutterstock

Visiting the site

As you approach Tiryns on the road to Nafplio, you’ll catch glimpses of the imposing Cyclopean walls rising from the surrounding landscape. The information boards at the ticket booth, produced by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, are packed with detailed site plans and an overview of its history.

Parts of the site are overgrown with wild flowers, especially the lower citadel, where the ground is strewn with loose rocks and rubble. As such, be sure wear appropriate shoes, suitable for walking on uneven terrain, and bring a hat, sunscreen, and water, as the site overs no shelter from the sun.

© Mythical Peloponnese

Up from the ticket booth you will encounter the monumental stone gateway on the east side of the citadel. In antiquity, this would have been adorned with a carved relief depicting two rampant lions flanking a central column, similar to the famous “Lion Gate” at Mycenae (the oldest monumental sculpture in Europe). This emblematic symbol not only served as a majestic entrance but also represented the power and authority of the Mycenaean rulers. Beyond the gateway lies a labyrinthine complex of courtyards, corridors, and buildings that make up the interior of the upper citadel.

As you explore, pause to take in the panoramic views of the surrounding Argolid plain and the sea. Consider the strategic importance of Tiryns’ location, perched atop a rocky outcrop that offered both natural protection and a vantage point for monitoring the region.

You will notice that the Cyclopean walls are still in an excellent state of preservation. As you wander around the perimeter, take time to explore the many tunnels and their high archways, located on the south and east walls, some reaching 20m in length. These tunnels were likely used for storage or as places of refuge in times of danger.

Many of the portable artifacts unearthed at Tiryns are now on display in the famous collection of Mycenaean antiquities at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Personal adornments and accessories like necklaces, gold rings, and decorative beads are presented, as well as pottery, seal stones, and fragments of clay tablets bearing the inscribed Linear B text, the earliest attested form of the Greek language. Invaluable historical documents, these clay tablets contain administrative records, inventories, and accounts, offering key insights into the economic activities and social structure of the palace complex.

© Public domain

Tiryns and the Heroic Age

The decline of Mycenaean civilization around 1200 BC, likely due to a combination of factors including environmental changes, internal strife, and external invasions, marked the end of Tiryns’ prominence. Nevertheless, even in terminal decline, the citadel and its adjacent settlement remained inhabited until the mid-5th century BC, when it was destroyed by neighboring Argos in its bid to assert total, regional control.

In light of its past glories, Tiryns occupies a notable place in Greek mythology, particularly in relation to the divine hero Heracles (“Hera’s Glory”), who used the citadel as a base to carry out the first two of his legendary Twelve Labors: the slaying of the Nemean Lion and the 9-headed Lernaean Hydra, terrifying creatures that were terrorizing the surrounding region. Heracles later used the lion’s impenetrable hide as a cloak.

In the mythological narrative, Heracles’ labors were imposed upon him as punishment for the murder of his wife and children in a fit of madness caused by the goddess Hera. King Eurystheus of Tiryns, a bitter rival of Heracles, assigned him these seemingly impossible tasks.

According to a later tradition, the city was originally founded by Proetus, who captured the site from his twin brother, Acrisius, the king of neighboring Argos. With the help of seven gigantic cyclopes from Lycia (southwest Asia Minor), Proteus occupied the outcrop and erected its famous walls. Through Proetus and Acrisius, Tiryns is also linked to the gorgon-slayer Perseus, Acrisius’ grandson, who went on to become the first king of Mycenae (learn more about Perseus’ miraculous conception here), thus placing the founding of Tiryns two generations earlier than its bigger and more famous sister-site to the north.

From the 7th century BC until its destruction by the Argives, Tiryns became an important cult centre for the worship Hera, Athena, and Heracles.