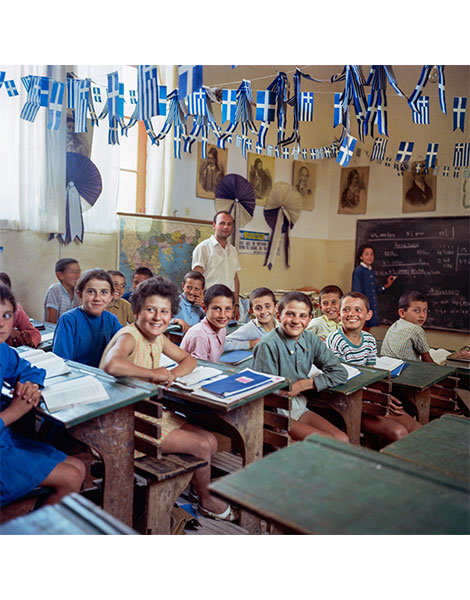

Epirus, Ano Peristeri, 1961. Labrini, Maria and Eleni smile while looking at the camera. The youngest of the three girls is barefoot and holds her tattered shoes in her hand. “The people who appear barefoot in my photos clearly are not going to a beach party. They are barefoot because, at the time, shoes were very expensive and any person who had shoes didn’t want to wear them out,” Robert McCabe tells me.

“And where is the hope that the title of your new book, “Greece After the War. Years of Hope,” alludes to?” I ask him.

“The smiles are the hope,” he replies. At the same time, he opens his mobile telephone and proudly tells me that it has 95,000 photos. In spite of his advanced age, Robert McCabe – “Bob” for those who know him well – is very good with technology. “The telephone has AI,” he explains to me.

As he scrolls through countless photos that represent decades of photographic work, he stops at a colored portrait of three middle-aged women. They stand arm-in-arm and look shyly at the camera. It’s a relatively recent photo of the three girls the 27-year-old American photographer had met back then which was taken οn the pretext of a photography exhibition in Monodendri. Through the years, the twinkle in their eyes has dwindled and their smiles have lost their youthful sparkle in spite of the fact that all three girls had shoes and were well dressed.

© Robert A. McCabe

© Robert A. McCabe

“Can you see the spirit of postwar Greece today,” I ask him.

“In some people, yes,” he responds. “Of course, in Athens relationships are very impersonal, but there are neighborhoods that are quiet like Anafiotika. There are also towns in Greece that are not very touristic, where relationships haven’t changed. When I arrived in Greece in the 1950s, there were only 180,000 foreigners every year, including diplomats, professionals and tourists. When we travelled to an island, it was normal not to see other foreigners other than ourselves. Even in the early 1960s, I remember that my brother, travelling to the island of Ios, wrote to me telling me that he discovered another “unchartered” island. We went there with our doctor from New York who had cancelled all his appointments at the last minute to come to Greece. When we arrived there, we discovered that there were five French tourists. My brother was so upset with the “throng” of people that he wanted to leave immediately.”

Robert McCabe comes from a family of journalists. Consequently, his photos encapsulate, apart from his personal aesthetics, an awareness that the camera is a witness to history. His father published the New York Daily Mirror – one of the first newspapers to publish photos – and young Robert had a dark room in his house where he would develop his photos from early on.

Robert studied French Literature at Princeton University and had a fondness for Europe and its culture. The adventurous spirit of the American youth of the 1950s drove the two young McCabes – Bob and his older brother Charles – to get on a boat and come to Greece. Their initial plan was to pass through Greece, but they eventually stayed, discovering a country untouched by modern civilization. Was it Greece after World War II, a country that always wore a smile despite its problems? Or was it Robert McCabe’s photographic eye that managed to capture moments of innocence at a difficult time for a troubled nation?

© Robert A. McCabe

© Robert A. McCabe

A beautiful country mired in poverty

“Greece After the War. Years of Hope,” with its rich archival work, will accompany the namesake photography exhibition of Robert McCabe at the Conference Center of the European Cultural Centre of Delphi (ECCD), which will be inaugurated on June 10. In Greece, the book was published by Patakis Publishers under the auspices of the ECCD, while the book’s English version is scheduled to be published soon by Abbevile Press which represents the author in New York.

In his preface, Robert McCabe describes his first visit to Greece in the summer of 1954, ten years since the Nazi occupation of Greece and five years since the end of the Greek Civil War. “The Greece I first saw was characterized in extreme poverty. That was visible everywhere. Often when one discussed with a Greek about the beauty of his country it would be followed by a “yes, but it is very poor” – and he would illustrate the point by rubbing his thumb and forefinger together“, he writes. And he continues “What I noticed visiting and later living in Greece was initially a slow recovery, which was subsequently followed by a remarkable growth and transformation into a modern European country. Greece was one of the poorest countries of Europe before the war –as such the road to recovery was long and difficult.”

© Robert A. McCabe

In Robert McCabe’s book, the President of the European Cultural Centre of Delphi and Professor at Harvard University, Panagiotis Roilos, who played a key role in the selection of the book’s photos, touches on the subject of the relationship between capturing memories and immortalizing moments. Referring to the historic context within which the material is included in the book, he notes that Greece began to steadily recover in the 1950s and 1960s. “The allies, primarily the Americans and the British, were eager to help but not without securing certain political, economical and military gains for themselves. During the time between the end of the Greek Civil War (1949) and the fall of the military junta of 1974, the political institutions in Greece were democratic essentially in name only,” he writes.

Nevertheless, he admits that there is something inherently nostalgic in the art of photography that “often creates a desire in people to “return” to a perpetual present without absences, ruptures in time or a past.” Is the Greece that the camera “captured” overidealized? Of course, as it occurs in all forms of art, creations are inspired by and imbued with the creator’s imagination. Thus, as Panagiotis Roilos concludes, there is “a fine line between a photograph’s functional use of recording events and capturing memories.”

© Robert A. McCabe

© Robert A. McCabe

The research on postwar Greece was carried out by journalist Katerina Liberopoulou. On the pretext of a photograph, namely a black and white photograph of a worker working intently at the site of the Herodus Atticus Odeon which in the mid-1950s was designated to become a center of the newly established Athens Epidaurus Festival, Katerina Liberopoulou sets 1955 “as a transitional phase between a period of horrendous hardships that were waning and a new and optimistic time of reconstruction which was dawning.”

Her account of Robert McCabe’s acquaintance with Greece ends where our text happens to begin: in Ano Peristeri, Epirus, at the meeting with Labrini, Maria and Eleni. “The three young friends are dressed in clothes that were probably made by their mothers. Although it is almost certain that their families had faced many misfortunes during the difficult years that had preceded, their smiling faces bring joy that after every hardship finds a way to continue with even greater impetus than before,” concludes Katerina Liberopoulou.

A roundtable on “The postwar Greece of Robert A. McCabe” will precede the inauguration of the photography exhibition at the European Cultural Centre of Delphi.

In addition, the Archaeological Museum of Delphi will also inaugurate the exhibition “Delphi of the 1950s through the lens of Robert McCabe.”

This article was previously published in Greek at kathimerini.gr