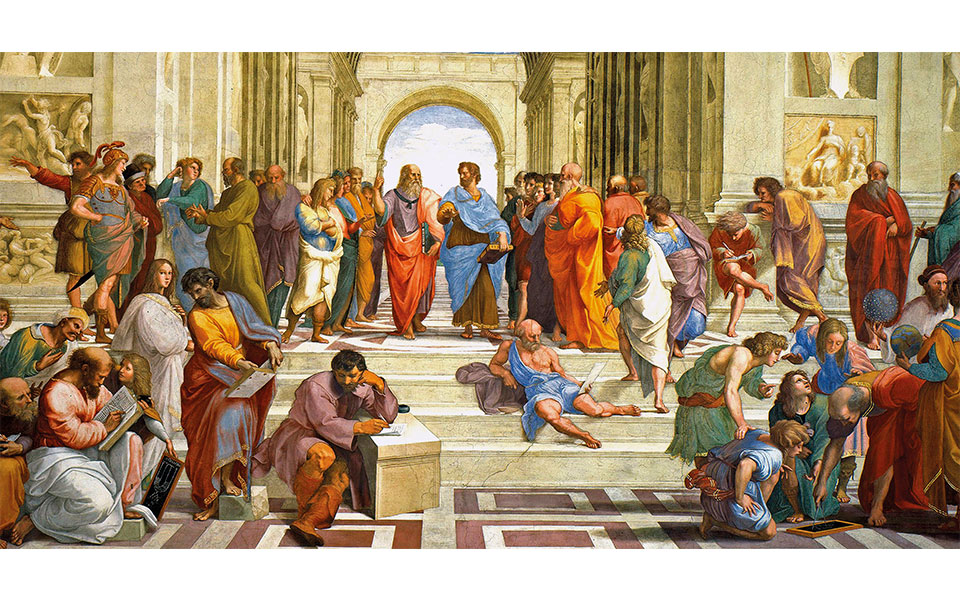

Ancient Greece is remembered for its extraordinary literature, art and architecture, but its greatest achievement was philosophy – intellectual thought, learning and discussion. The Greek world was a land of philosophers in the 6th, 5th, and 4th centuries BC, where great thinkers emerged and flourished even in its remotest corners; from Pythagoras and Epicurus of Samos and Heraclitus of Ephesus (western Asia Minor) to Thales of Miletus, Democritus of Abdera in Thrace, Aristotle of Stageira in Chalkidiki, Empedocles of Akragas in Sicily (Magna Graecia), and, of course, Anaxagoras, Socrates and Plato of Athens. The philosophers were teachers, examiners of the physical and metaphysical world, and often travelers. Ultimately, it was to Athens, a renowned philosophical center, that they were drawn, thanks mainly to the towering figures of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, who attracted followers, established schools and left eternal legacies.

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

In their footsteps…

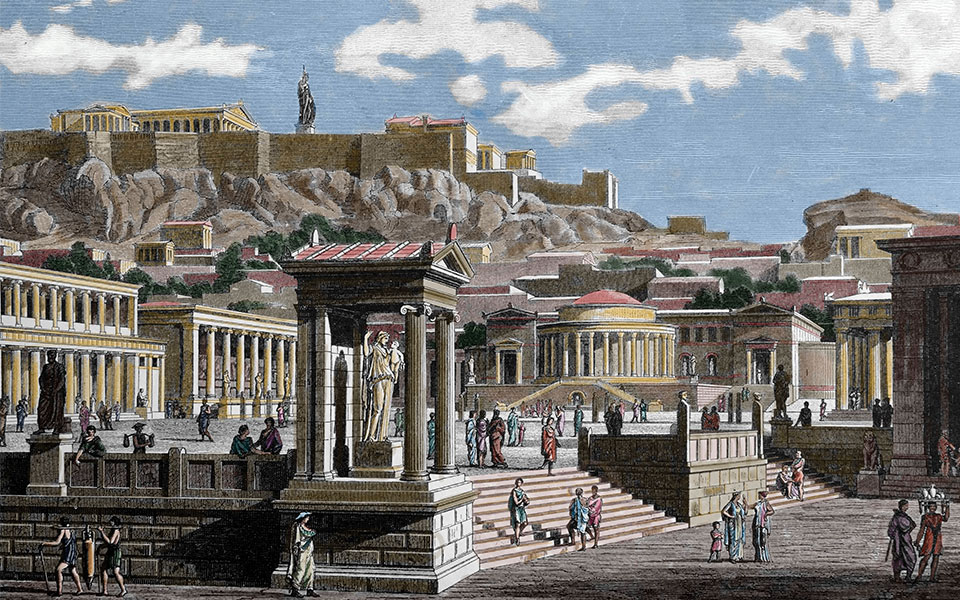

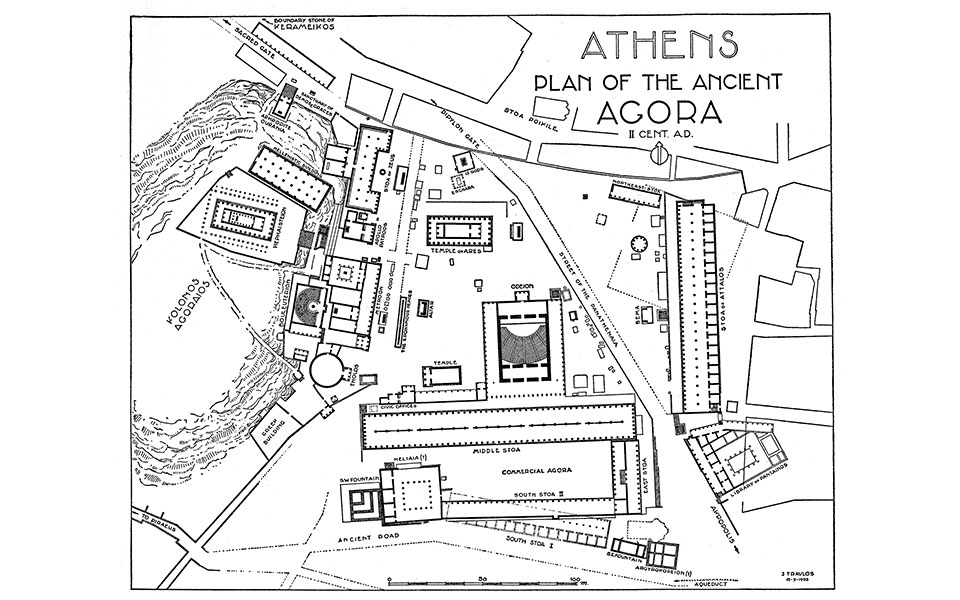

Can we now trace the footsteps of Greek philosophers across the age-old landscape of central Athens? Where exactly were the philosophical schools and daily haunts of these early “influencers”? The evidence for the philosophers’ movements and favorite hang-outs in Athens comes to us through a combination of historical sources and archaeological evidence. The actual locations of Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum are today archaeological sites or parks, while Socrates’ “school” operated beneath shade trees, out in the ancient city streets, or within public buildings and private houses.

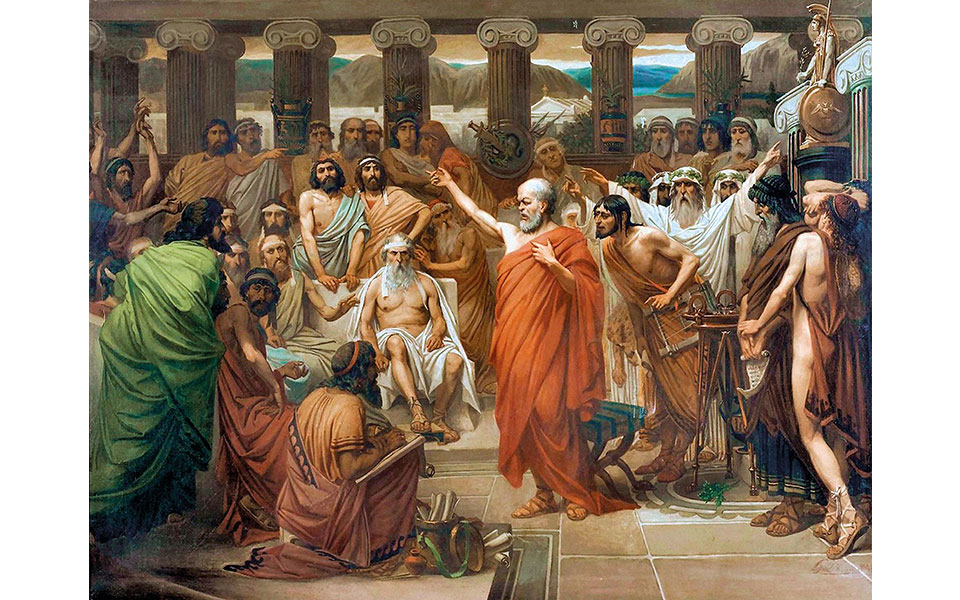

Although Socrates himself never wrote anything, his students Plato, Xenophon, and Aeschines of Sphettus (an Athenian deme) documented his teachings through their firsthand knowledge of him. With ever more specific and probing questions, he examined contrasting concepts such as godly/ungodly; beautiful/ugly; just/unjust; prudence/madness; and courage/cowardice. What, he asked, is a state, a government, or a statesman? Socrates, believing that knowledge of these subjects “made one a gentleman,” strove to cultivate the minds of Athens’ aristocratic youths. In the end, however, having angered their politically sensitive elders, he was tried and convicted of trumped-up crimes, imprisoned near the central marketplace, and forced to drink poisonous hemlock. Today, we can visit specific spots frequented by Socrates and other famous philosophers, not only in the Athenian Agora but elsewhere in the ancient city, where words, objects, and a healthy imagination allow us to revisit and envision delightful conversations and a now long-regretted death.

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

The Athenian Agora

In the heart of ancient Athens lay its central square and marketplace, the Agora, which almost every adult who inhabited the city, not to mention its leading citizens, likely visited at one time or another. Since 1931, the Agora has been the subject of archaeological excavations and remarkable discoveries by the American School of Classical Studies, with numerous buildings mentioned in historical texts being brought to light. To better understand the Athenian Agora, the ancient Greek language itself is revealing. The verb “agorazo” meant “to frequent the agora” and “to buy” things, while “agorevo” described the action of speaking in the Assembly, as well as the speech acts of haranguing, saying, and proclaiming. Indeed, the main activities in the Agora were talking, meeting one’s friends and associates, and catching up on the latest news buzzing around the city. As a place of gathering, it also became a central spot for merchants, moneylenders, vendors, street performers, and governmental officials, including lawmakers, judges, and citizen-participants in the daily operations of the Athenian democracy and judicial system.

As archaeologist Mabel Lang relates in her now-classic 1978 Agora handbook, Socrates was a frequent visitor and familiar sight in Athens’ central square and surrounding neighborhoods. There, he strolled along the bustling lanes, attended court proceedings and Council meetings when required, or, encountering a devoted follower or another target ripe for questioning, ducked into a convenient portico to repose in the shade and converse.

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

Athens’ colorful characters

Socrates was the son of a stoneworker/sculptor, in whose profession he was also trained. As an older man, his physical appearance caused him to be viewed as almost a comical or Dionysiac character – comparable to a pot-bellied satyr or even the great silenus Marsyas – thanks to his bulging eyes, wide out-turned nostrils and thick lips. His disregard for material comforts and regular bathing, as well as his unkempt clothes and perpetually bare feet, made him a subject of both ridicule and respect.

Among Socrates’ young aristocratic followers, however, not everyone agreed with his ascetic lifestyle and his refusal to accept money for services provided. Isocrates, for example, adhering more to the ways of his other mentors, who were sophists and rhetoricians, went on to become a hired speechwriter and frequented the city law courts in search of clients.

Asceticism was later famously embraced by Diogenes of Sinope, one of 4th century BC Athens’ most colorful philosophical characters. As Socrates had, he resisted convention and challenged society’s values. In fact, by today’s standards, we might categorize him as a homeless person, as he lived in an enormous, discarded storage jar (pithos) somewhere in the Athenian Agora and took great pleasure in shocking people with his perverse displays of behavior. He described himself, reports the Roman biographer Diogenes Laertius (3rd c. AD), as “a Socrates gone mad.” The same source recounts how he also baited the city’s more conventional, mainstream philosophers. Once intruding at the Academy – when “Plato had defined Man as an animal, biped and featherless, and was applauded – Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into the lecture-room with the words ‘Here is Plato’s man.’”

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

A philosopher on every corner…

Although preeminent among ancient Greece’s “word-merchants,” Socrates (ca. 470-399 BC) was neither the first nor the only great thinker to haunt the Agora and its environs. Among the numerous Pre-Socratic philosophers (e.g., Thales, Heraclitus, Empedocles), few may have ever stepped foot in Attica. Anaxagoras of Clazomenae (Asia Minor), however, came to Athens sometime around 456 BC, while Pythagoras of Samos likely stopped in Piraeus and Athens en route to Croton in Magna Graecia. Like many of his contemporaries, Anaxagoras was concerned with the nature of existence, the mind, and the cosmos. Among his insightful theories, he correctly explained eclipses and claimed the sun was a mass of red-hot metal, the moon was earthy, and the stars were fiery stones. Anaxagoras became well known in Athens, familiar to Sophocles, Euripides, Aeschylus, and Aristophanes. He was also a close friend of Pericles. In the Agora, Socrates noted, the youth of Athens could at times buy the writings of Anaxagoras “for a drachma in the orchestra,” a central area where singing, dancing and plays were performed. In Plato’s “Phaedo,” Socrates recalls: “One day I heard a man reading from a book…by Anaxagoras.”

The sight of philosophers hanging about in the city center became even more commonplace during the 5th century BC when a stream of traveling teachers began arriving in the intellectual and democratic artistic incubator that was Periclean Athens. Protagoras of Thrace led this influx of professional educators, known as “sophists,” which included Prodicus, Gorgias, Hippias, and Thrasymachus. Although some were acquaintances and teachers of Socrates, he condemned their practice of accepting payment for sharing knowledge. He also focused his inquiries on aspects of morality, rather than on more traditional questions of natural science. The Athenian public attending comedies in the Theater of Dionysus or other such venues would also have been familiar with Socrates, as Aristophanes often poked outrageous fun at him and the sophists (making no distinction between the two) in various plays, including “The Clouds.”

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

Bouleuterion & Tholos

On the Agora’s western side stood a row of buildings which, along with the meeting place of the people’s Assembly (Ekklesia) on the nearby Pnyx Hill, was the seat of Athens’ democratic government. Everyone was expected to participate, and Socrates’ experience illustrates how seasoned statesmen regularly worked shoulder to shoulder with ordinary citizens unfamiliar with the mechanics of politics. In Plato’s “Gorgias,” Socrates admits: “…Last year, when I was elected a member of the Council [of 500] and, as my tribe held the Presidency, I had to put a question to the vote, I got laughed at for not understanding the procedure.” As a senator, Socrates would have sat in the Bouleuterion; when his tribe served as executive council members (prytaneis), he would have resided and eaten state-sponsored meals in the neighboring Tholos building.

The Painted Stoa

Later, Diogenes’ philosophy of Cynicism was taken up by Zeno of Kition (Cyprus), who based himself after 301 BC in the Painted Stoa (Stoa Poikile) on the north side of the Athenian Agora. Zeno’s distinct philosophical approach gained its name – Stoicism – thanks to his followers, the Zenonians, who came to be called “Stoics” due to their ubiquitous presence at the Painted Stoa.

“The Garden”

A contemporary of Zeno was Epicurus from Samos, a controversial figure whose philosophy would be both embraced and despised, until finally being eclipsed by Stoicism and condemned by Christianity in the Roman era. Arriving in Athens in about 306 BC, Epicurus was influenced by Socrates’ hedonistic student Aristippus. He established his own school, The Garden, on property located somewhere between the Academy and the Painted Stoa.

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

The Royal Stoa

Also in the northern area of the Agora was the Royal Stoa (Stoa Basileios), where the King Archon held office. This chief Athenian magistrate presided over the city’s religious affairs and homicide trials. It was here that Socrates met the Athenian divinator Euthyphron, as Plato relates, on a morning when they were both waiting for the start of preliminary hearings in their respective trials for impiety and murder. Euthyphron was there to prosecute his own father for causing the death of a worker. They may have sat on the stoa’s colonnaded porch or in its flanking wings, where the Athenian constitution was displayed on inscribed marble steles, or perhaps in the shade of a nearby tree, and discussed the nature of justice and piety. Through Plato, we learn a little about Socrates’ habits and background. Euthyphron says, “What strange thing has happened, Socrates, that you have left your accustomed haunts in the Lyceum and are now at the portico where the King Archon sits?” Later, the sculptor-turned-philosopher refers to the mythical Daedalus as “my ancestor” and lightly suggests he may be “a more clever artist than Daedalus; he made only his own works move, whereas I give motion to the works of others as well as to my own.”

The Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios

Another favorite among Socrates’ hang-outs was the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios, a large portico just south of the Royal Stoa, where he walked and talked or simply sat. Aeschines (in Miltiades) reports seeing Socrates sitting there once with the playwright Euripides – both apparently trying to avoid the boisterous, noisy crowds attending the Greater Panathenaia procession. Two pseudo-Platonic dialogues, the Eryxias and Theages, also reveal this stoa as a calm oasis within the Agora. When Demodocus approaches Socrates requesting a private conversation, he asks “Do you mind if we step aside here from the street into the stoa of Zeus Eleutherios?” Furthermore, Socrates himself recounts: “Happening one day to see [Ischomachos] in the stoa of Zeus Eleutherios apparently at leisure, I approached, and sitting down at his side, said: ‘Why sitting still? Generally, when I see you in the marketplace, you are either busy or at least not wholly idle.’”

© AFP/VISUALHELLAS.GR

Loitering in the sunshine

Socrates enjoyed the outdoors. He was “ever in the open,” Xenophon says. “Early in the morning, he went to the public promenades and training grounds; in the forenoon, he was seen in the market; and the rest of the day he passed just where most people were to be met….” In particular, he was “accustomed to speaking…at the bankers’ tables” in the Agora, where the moneychangers and lenders operated. These may have been temporary tables, set up when necessary and where appropriate, similar to those used today by vendors in Greece’s popular “laiki” street markets. Socrates was also known to make regular sacrifices at public altars, erected in the Agora, the Academy’s sacred grove, and elsewhere.

Craftsmen, shops and houses

Being concerned more with human issues, Socrates conversed with Athenians from all walks of life, from humble craftsmen and merchants to affluent symposium-goers. Painters, sculptors, and armorers were all his subjects or interlocutors, while a particularly devoted follower was a leatherworker named Simon, who made saddles, reins, and sandals. The shop and courtyard of “Simon the Shoemaker,” where Socrates and his underage disciples probably sat, has been unearthed just outside the southwestern boundary of the Agora. Eyelets, hobnails, and a black-glazed cup base inscribed with “Simonos” reveal the industry practiced there. Simon apparently took copious notes during Socrates’ visits, as Diogenes Laertius mentions a book he wrote containing thirteen works known as the “cobbler’s dialogues.”

The area southwest of the Agora was packed with private dwellings, workshops, the law courts (Heliaia), and the state prison. It may have been in this neighborhood that Socrates and his friends attended the drinking party of Agathon described in Plato’s Symposium. We don’t know precisely where Agathon’s home was, but typical houses fitting the dialogue’s narrative details have been found there. Running through the area is the Street of the Marble Workers, which appears in a humorous story about Socrates told by Plutarch (1st/2nd c. AD). One day, while passing through this district in a group, Socrates had a premonition and abruptly changed course, leaving some of his companions to carry on down the narrow street of the “statue-carvers.” Soon “they were met by a drove of swine, covered with mud and so numerous that they pressed against one another. As there was nowhere to step aside, the swine ran into them, knocked them down, and befouled the rest.” Socrates continued unscathed, but his friends returned home covered in filth, and afterward always recalled their mentor’s inner “feelings” with laughter.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Gymnasia and palaestrae

The many gymnasia (training centers) and palaestrae (wrestling schools) of Athens were a particular magnet for Socrates and other philosophers, as they were often filled with young men seeking exercise, sport, and education. They were usually in outlying areas with springs and enough space to accommodate a running track. Socrates mentions stopping at one such place while walking from the Academy to the Lyceum along the northern road just outside the city wall. As he passed a small gateway leading to the fountain of Panops (All-Seeing Hermes), he was hailed by a group of youths standing in front of a walled palaestra, who invited him inside for discussion. Today, this once-pastoral spot may lie in the vicinity of Stadiou Street, between the Panepistimiou metro station and the Greek Parliament.

On campus

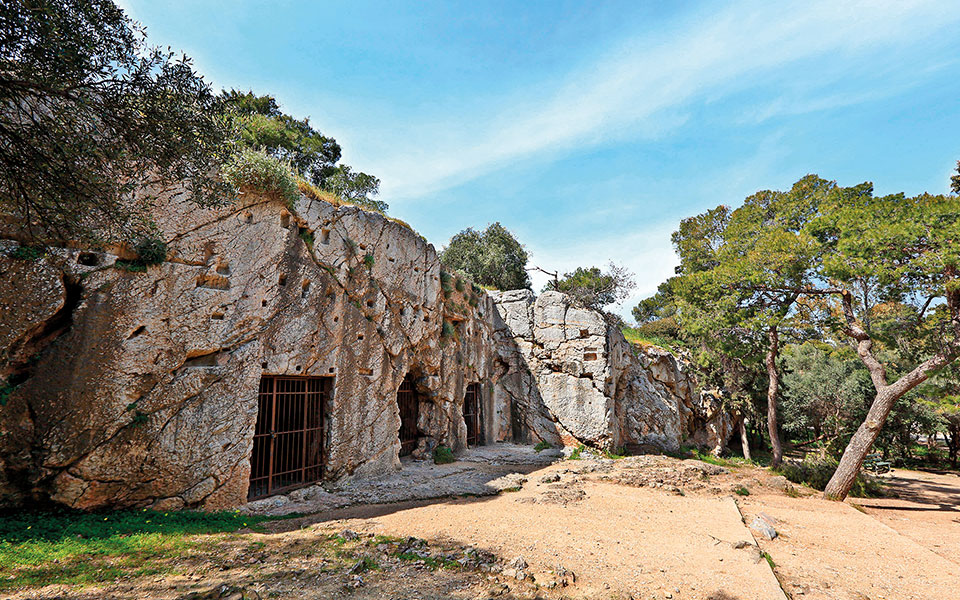

The three major gymnasia of 6th-4th century BC Athens were the Academy, the Lyceum, and the Kynosarges, located north, east, and southeast of the ancient city. The Academy, named for the local hero Hekademos, had long been a sacred area, dry and treeless until the statesman Cimon irrigated it from the nearby Kephissos and Eridanos rivers. By Socrates’ time, it was already considered the most beautiful district outside walled Athens. Its cool, shady olive grove, dedicated to Athena, would have been an attractive place for philosophers and their students, who could reach this parkland after walking about 8 stadia (1.5 km) from the Dipylon Gate in the Kerameikos quarter. Plato, from an affluent family in the area, established his school in ca. 387 BC at his own home, west of the Hippios Kolonos hill. The school’s “campus” was further developed in the following centuries with additional buildings. Today, a grassy park covers the Academy, where archaeologists have revealed a large late Hellenistic-early Roman gymnasium.

Also pastoral and well-watered was the Lyceum district, east of present-day Syntagma Square. Bounded on the north by Lycabettus Hill and the Eridanos River (beneath Vas. Sofias Ave.), and on the south by the Sanctuary of Olympian Zeus and the Ilissos River (beneath Vassileos Constantinou/Ardittou/Kallirois), it was initially sacred to Apollo Lykeios, a protector of herds and flocks from wolves. The Lyceum’s athletic facilities were already used by sophists (e.g., Protagoras, Prodicus) before Socrates’ time, while Isocrates later taught rhetoric there. In 335 BC, Plato’s student Aristotle returned to Athens, taking over a Lyceum building for his “Peripatetic” school – so named for the site’s covered walkways (“peripatoi”) or for his habit of walking while speaking with students. Aristotle’s Lyceum contained a library and sample collections of plants and animals, significantly contributed to by his former pupil-turned-conqueror Alexander. As a place of education, teaching, and research, it represented the Western world’s first “university.” Today, visitors to the archaeological site beside the Byzantine Museum can view the foundations of a palaestra, founded 350-300 BC.

© ALAMY/VISUALHELLAS.GR

The riverbank

One of the lushest, most picturesque districts of Athens frequented by philosophers was the Ilissos River and its far bank, southeast of the Acropolis. On the near bank, below the Olympieion, were smaller temples, law courts, altars, and shrines; on the far bank stood the temple of Artemis Agrotera (the Huntress) and the Kynosarges athletic complex, including a running track and one or more gymnasia. It was here that Antisthenes, Socrates’ student, established his school of Cynicism, a name perhaps derived from the Kynosarges gymnasium itself. Diogenes, Zeno, and Epicurus later may all have received instruction at this place, now obscured beneath the junction of Ardittou, Kallirrois, and Vouliagmenis avenues.

Socrates once met Phaedrus outside Athens, and together they strolled past the Olympieion. In Plato’s account, Socrates says: “Let us turn aside here and go along the Ilissos.” They walk barefoot in the stream, eventually crossing to reach a small wooded valley – where the Panathenaic stadium was later built. They sit beneath a plane tree to talk; Socrates, remarking on the beauty and fragrance of the shady spot, notices a nearby shrine of Pan, Achelous and the nymphs, adorned with figurines and statues. Nowadays, we can only listen to Socrates and imagine this idyllic setting. He observes: “The spring is very pretty as it flows under the plane tree, and its water very cool, to judge by my foot… Then again…, how lovely and… charming the breeziness…, [and] the shrill summer…chorus of cicadas. But most delightful…is the grass…on the gentle slope…”

Darker days and a regrettable death

Socrates’ pleasant ramblings came to an end in 399 BC when he was accused of impiety and corrupting the Athenian youth. His trial was likely held in the southwestern Agora area, as we know “the court…was near the prison.” Both the Heliaia court and the State Prison are visible today. When his followers last visited him in his cell after he had been convicted and sentenced to execution by drinking hemlock, his fetters had just been removed, and his wife Xanthippe sat beside him, “his little son in her arms.” She cried out: “Oh Socrates, this is the last time now that your friends will speak to you or you to them.” He replied: “‘I…pray to the gods that my departure hence be a fortunate one….’ With these words, he raised the cup to his lips and very cheerfully and quietly drained it.”