Τhe devastation of a city is a tragic event, with painful consequences to the social and economic life of its population, to the progress of local development, to the expectations of its residents and to their daily lives.

But large-scale destruction almost inevitably unleashes reparative processes which, in other circumstances, would require different timeframes and methods. The history of cities shows that modernizing interventions and the complete redesign of the urban landscape have followed every great catastrophe.

This was also true in the case of Thessaloniki. It is, however, something of a paradox that two major events in the city’s history, namely the Great Fire of 1917 and the redevelopment of the historic center in the interwar period, were subsequently almost forgotten, perhaps because times were so difficult and events (the mass influx of refugees from Asia Minor, the German occupation, the Holocaust, civil war and emigration) so painful.

© Thessaloniki – Moments of History, National Historical Museum, Athens 2016

The old town and the traditional layout

Up to 1869, the city was still enclosed within Byzantine walls that stretched for eight kilometers, retaining the spatial form it had acquired in the 7th century. Inside the walls, the inhabitants lived in separate neighborhoods according to religion and ethnic origin, in contact with each other but not integrated.

The Mediterranean climate favored outdoor collective living while, as in other towns and cities of the eastern Mediterranean, workshop and market activities developed away from the residential areas. The streets of the commercial district, full of traditional products from the East, were covered by awnings that provided protection from the sun and rain.

By bringing legislation and institutions more into line with Europe and granting equal rights to non-Muslims, Ottoman reforms had a significant impact on the form and layout of towns and cities, which attracted new urban social strata, including administrators, entrepreneurs, traders and company employees.

Within the framework of the Ottoman reforms, the face of the city began to change in 1869 with the demolition of the coastal wall and the creation of an extensive waterfront. As the city opened up, new districts were created to the west and east of the center within the walls.

According to the 1913 census, the city’s population was 157,889, comprising 61,439 Jews, 39,956 Orthodox Greeks, 45,867 Turks, 6,263 Bulgarians and 4,364 “foreigners.”

The high population density in an already aged housing stock, frequent fires, economic fluctuations and the absence of any social housing dramatically exacerbated the housing problem and the poor sanitary conditions in the city. Slums had developed in the western districts outside the walls and in parts of the historic center. Next to the “camps” of the poor and the refugees, a number of “Europeanized” districts appeared with new types of buildings and new architectural forms.

According to the 1913 census, the city’s population was 157,889, comprising 61,439 Jews, 39,956 Orthodox Greeks, 45,867 Turks, 6,263 Bulgarians and 4,364 “foreigners.”

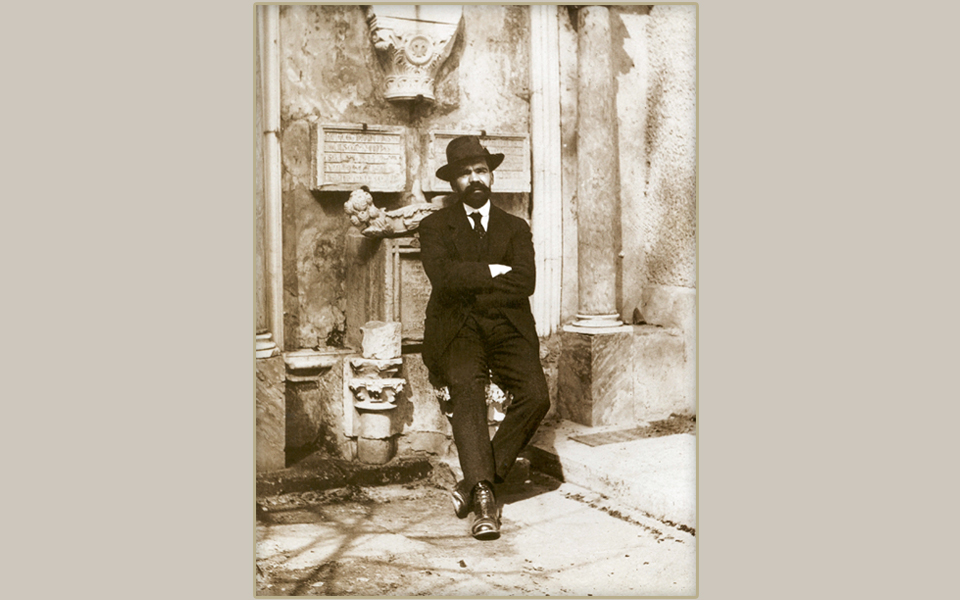

© Haris Giakoumis Collection, from “Ernest Hebrard, 1875 – 1933, Potamos Publications, Athens, 2001

The 1912-1922 period

The incorporation of most of northern Greece into the Greek state was accompanied by extensive depopulation in towns and cities, particularly in Eastern Macedonia. Only Thessaloniki constantly received new inhabitants, resulting in a sharp increase in its population.

The Great Fire that broke out on August 18, 1917 marked a turning point in the history of the city, since it completely destroyed a housing stock that had been shaped over the centuries. The fire indiscriminately ravaged the stone-built new districts on the waterfront and on Aghias Sofias Street, the medieval covered markets and the sprawling, densely inhabited and labyrinthine slums that occupied the greater part of the historic center. Some 9,500 buildings went up in flames and more than 70,000 people (52,000 Jews, 11,000 Muslims and 10,000 Christians) were left homeless.

Financial institutions, businesses, administrative offices and the most important cultural and religious institutions of the ethno-religious communities and their archives (including 16 synagogues and the seat of the Chief Rabbi, 12 mosques and three churches, among them the centuries-old Church of Aghios Dimitrios) were completely destroyed. Strangely enough, no fatalities were reported.

The fire essentially erased the “oriental” aspect of the city’s character and eliminated the traditional characteristics that had survived despite previous efforts at modernization. The plan devised for Thessaloniki by an international planning committee, under the supervision of its chairman, the French architect Ernest Hébrard, provides an interesting insight into urban planning at the time.

The city within the walls was redesigned from scratch, as if it were a blank canvas, without any of the various constraints normally imposed by time, historical events or ownership.

The plan and the modern city

Despite extremely difficult conditions, most of the Hébrard plan was implemented. It introduced wide boulevards within a hierarchical road network, brought together public services, created a civic center (around Aristotelous Square), established a rational organization of spaces for production and consumption, gave city blocks and land plots a regular shape, highlighted the wealth of monuments dating to the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, preserved certain picturesque neighborhoods and set aside open spaces for squares and parks.

The plan envisaged a doubling of the population within a peripheral green zone, beyond which the city would not be allowed to expand. Separate plans were also made for the soon-to-be-founded University of Thessaloniki, for workers’ districts, and for industrial zones.

The committee also made an important contribution to the development of a new type of collective housing, the apartment building, while the notion of “horizontal property” appeared for the first time. The planners’ intention was that the population would not surpass 350,000 and any numbers in excess of this figure would be housed in other towns and cities of the region.

The city acquired new port installations, networks and infrastructures; straight wide roads ready to accommodate the constantly increasing number of cars; and building regulations that mandated the use of a new material – concrete – for the erection of four-story and five-story buildings.

The plan for Τhessaloniki after 1917 is important because it introduced a renewed form for the modern Greek city, one which responded to the demands of the new industrial society.

© “Ernest Hebrard, 1875-1933”, Potamos Publications, Athens 2001.

The rationalization of the various commercial, religious, medical and administrative functions, and the business principles on which the planning of the city was based, clearly modernized the city’s appearance, but it also resulted in the disappearance of valuable, even unique characteristics, which – however – nobody cared about at the time.

Most of the institutions – chiefly non-profit – which had traditionally existed in the historic center (such as the numerous synagogues, mosques and türbe mausoleums, post-Byzantine churches and chapels, inns, orphanages and nursing homes) were not re-established in the center, and only some were moved to the newer districts of the city.

The plan for Thessaloniki after 1917 is historically important because it introduced a renewed form for the modern Greek city, one which responded to the demands of the new industrial society and to the optimism of the technocrats who held power. Limited government resources, exceptional occurrences (the influx of refugees) and the incomplete urbanization of Greek society did not, however, allow the state to bear the cost of modernizing other towns and cities, nor for civil society to undertake relevant initiatives.

Despite the extremely adverse historical conditions that followed the first years of reconstruction, Thessaloniki – by taking advantage of disaster – did not miss the opportunity to renew itself.

*Alexandra Yerolymbos is Professor Emeritus of Architecture and Urban Design at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. This article is based on ideas and themes included in work published by her in 1985, 1997, 2008 and 2016 and was first published in the magazine Parallaxi.

© Thessaloniki – Moments of History, National Historical Museum, Athens 2016

“Bitter Bread That Water Wouldn’t Wash Down”

By Amber Charmei

“It was an indescribable scene, one might say biblical, were it not for the sewing machines and broken mirrors… thrown into the narrow alleyways…”. This was what Henry Collinson Owen said about the great blaze that consumed so much of the city; when he first saw smoke coming from the Turkish quarter during tea time, though, the British journalist wasn’t particularly alarmed – small fires were fairly common.

Ironically, the conflagration started near a square once called Horhor Su, meaning “Where Water Flows.” Not that day, though – the water had been diverted to the soldiers of the Allied armies quartered nearby. A northwesterly wind known locally as the Vardaris was blowing hard. It hadn’t rained since June.

As the fire spread, Owen noted how: “…the streets filled with wailing families, the crash of falling houses as the flames tore along, swept by the wind… a slow-moving mass of pack-donkeys, loaded carts… people carrying beds (hundreds of flock and feather beds), wardrobes…” The crowds made their way to the harbor, where soldiers helped them to board British ships. It wasn’t, however, all chaos – newsreel footage shows fashionable women (the women of Thessaloniki have always been known for their style) strolling along the promenade against a backdrop of smoke. Hours later, the seafront was a wall of flame so intense that the fire jumped to boats docked there.

Info

Archaeologist Tassos Papadopoulos of Thessaloniki Walking Tours shared these insights during a tour about the fire. Excerpts also taken from Salonica: City of Ghosts – Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430-1950 by Mark Mazower (Vintage Books).

After the fire, the poorest camped illegally in the burned-out ruins. Some buildings, like the Church of Aghios Dimitrios, were not rebuilt for decades. Writer Giorgos Ioannou grew up alongside them: “The more the structure took shape again, the colder it seemed. The impression that never completely faded… was that the ruins had been more spiritually moving.” That which didn’t burn, melted – locksmith Judas Solomon, skilled at getting melted safes open again, did a brisk business.

One stroke of fortune was that it was the Jewish Sabbath, so parts of the city were relatively empty. There was not a single recorded death. It was, however, the end of life as they knew it: centuries of multicultural heritage were lost – mosques, hans, synagogues. The beer halls and cabarets – the city has always loved a good time – were gone, too. The poignant Ladino lyrics of David Saltiel’s El Incendio de Salonica describe what life was like for the 72,000 left homeless: “Tanto povres como ricos todos semos un igual/ Ya quedimos arrastando por campos y por kishlas…. Mos dieron pan amargo ni con agua no se va…” (“Rich and poor alike, we all became one/We were left out in the fields and barracks…. They offered us bitter bread that water wouldn’t wash down…”).

The city was united in grief. Representatives from each of the three religious communities called for the acquittal of Paraskevoula Adam and Domna Savvoglou, popularly thought to have been frying eggplant when a spark from their stove started the fire. It could have happened to anyone.