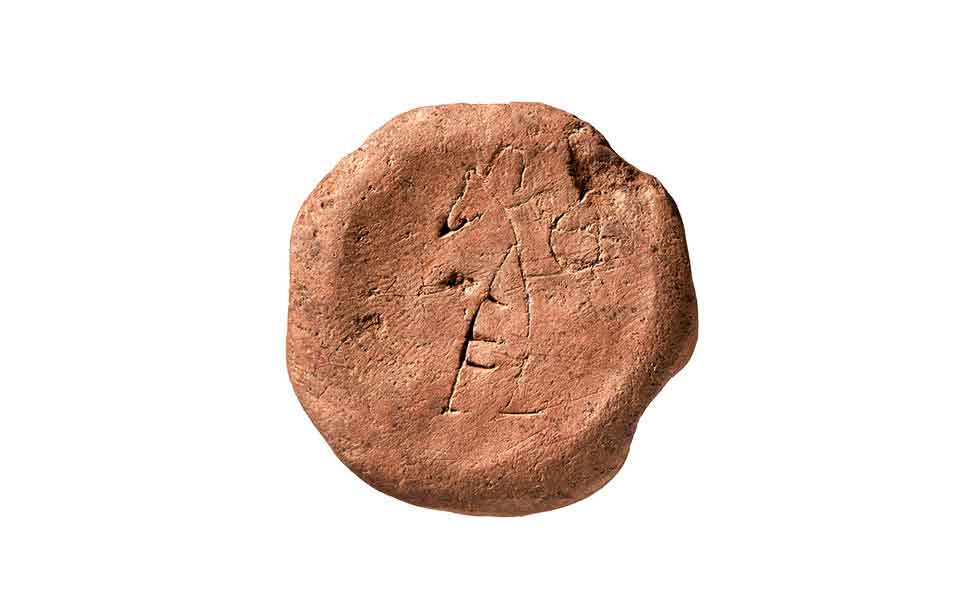

Discovered in the early 1980s, the famous “Seal of the Ruler (or Hegemon),” dated to the mid-15th century BC (Late Minoan period/Late Bronze Age), was the first indication of something much bigger lurking under the surface of Kastelli Hill, in the heart of the Old Town of Hania. The tiny circular seal impression, made of clay, depicts a complex of multi-storey buildings on a rocky coastal hillside, above which stands an imperious-looking male figure wearing a Minoan kilt and holding a scepter or spear.

Later, archaeologists made the discovery of an extensive sacrificial site on the hill, where, in addition to the huge number of animal remains, were the bones of a young woman; possible evidence of a human sacrifice to appease the gods, carried out after the devastating earthquake of the 13th century BC.

Most recently, excavations by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Hania in October and November 2022 have come one step closer to confirming the existence of a vast palace complex that once dominated the area in the 14th and 13th centuries BC, the political center of the ancient region of Kydonia in the Minoan and Creto-Mycenaean periods. Last year’s excavations focused on the remains of a large, hypostyle hall (its roof supported by columns), which, archaeologists believe, may have served as a public space for administrative or religious activity.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Antiquities of Hania, Crete

Wooden Columns

“We found more bases of wooden columns, which show the hall was divided by two colonnades into three aisles, and had an area of at least 200 square meters,” says Maria Andreadaki-Vlazaki, director of the excavations at Kastelli and Honorary general Director of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage.

“The hall,” she continues, “could not have belonged to a simple residence but a large gathering place, perhaps an administrative or religious area of the palace we know must have existed on the hill.” Intriguingly, between the two colonnades was discovered the traces of a wooden piece of furniture, possibly a seat, which was placed on a stone slab. Andreadaki-Vlazaki does not believe that it necessarily functioned as a “throne,” as further research is needed, but more general features of the site support the idea that the hall formed part of a huge palatial complex.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Antiquities of Hania, Crete

Crete has Minoan palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Zakros, and Malia, as well as at Kastelli Pediados, Zominthos and Archanes. If confirmed, “the palace of Kydonia would have been among the largest on the island,” added Andreadaki-Vlazaki. “It would have been the most important in western Crete, certainly during the Creto-Mycenaean period, when the Mycenaeans [of the Greek mainland] held sway over the island. At some point, the palace would have played a primary role in the economic, administrative and religious affairs of the state. The key difference is that the palace is not surrounded by countryside, unlike the others, but in a heavily populated area. This has been the case since the 4th millennium BC.”

The modern-day urban landscape of Hania, with its many layers of ancient settlement, make it difficult for an excavation that began decades ago to progress at speed. The archaeologists can only focus one small section at a time, year after year. Even so, with the help of new scientific methods and techniques, more data is gathered than in the past. For example, the ability to collect and analyze aDNA (ancient DNA) from the skull of the young woman, ritually killed after the earthquake of the 13th century BC, has conclusively shown that the inhabitants of Late Bronze Age Kydonia were genetically distinct from people with imported characteristics from mainland Greece.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Antiquities of Hania, Crete

Minoan Warrior

Among the portable finds discovered during last year’s excavations, one of the most interesting is a circular clay tablet with a Linear A ideogram, depicting a warrior with a shield.

In one of the later layers, the archaeologists found a hoard of 33 silver coins, mainly staters from the 4th century BC, which, according to Andreadaki-Vlazaki, is “an impressive and unique find.” She adds: “They come from at least 13 cities across Crete, which is something you don’t come across very often. We may be dealing with a concentration of wealth from an island-wide endeavor and their concealment due to a sudden emergency. The coins of are high value and, due to their excellent state of preservation, are easily recognizable.”

The excavation project, which is being carried out with the ultimate aim of making the site accessible to the public, receives funding from the Institute of Aegean Prehistory and is being overseen by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Hania, a part of the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports.

This article was previously published in Greek at kathimerini.gr.