Growing up a small-town girl, I’ve never really gotten used to Athens. The fast pace, the crowds, and the lack of green or even space between the apartment buildings (and the municipalities) always made me feel just slightly small and out of place. The exception, the one place that feels like mine, is the center and coast of Piraeus.

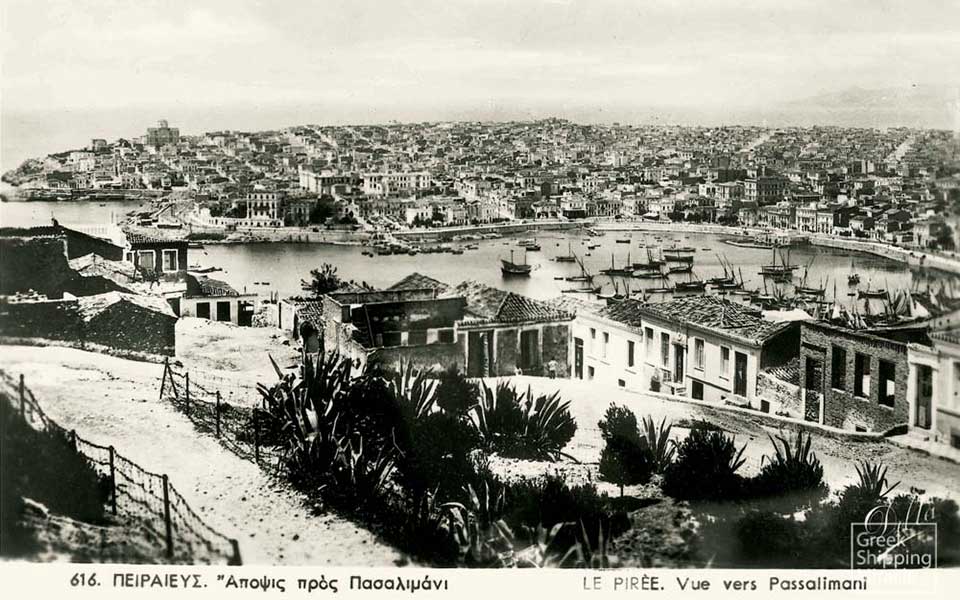

In the port city, where I lived for years, the uncluttered view of the sea and the suggestive pull of the ships moving in and out of the port, reminding me of the constant easy access to my beloved islands, allow me to breathe.

Unfortunately, for a long time, while my head was turned towards the sea, I didn’t pay much attention to the city that owns part of my heart.

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

We love to promote Greek cities for their long history; how they’ve existed in the same place for thousands of years – and that we’re all just a tiny part of their story. There’s been a port in Piraeus since before 2000 B.C., and it’s been a base for the Athens fleet since the battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. All residents of the city know that while the port has been damaged or completely destroyed in several wars (most recently during WWII), it’s always come back stronger.

Less often do we talk about what a place was like before a city spread across it, or how rapidly they might have been built. Essential to getting to know Piraeus is recognizing that aside from ships anchoring in the port, the rest of the city as we know it is relatively new. In fact, the city in which I spend my days was nothing more than two tiny settlements until 1830. One could likely count the houses of each with a quick glance. Like much of the rest of the Attica basin, until that time, the land that is now a city was mostly empty.

So how did Piraeus come to be? Who built it – and why?

© Shutterstock

Clio Muse Audio Tours

To get to know Piraeus better, I downloaded a tour through the app of Clio Muse – an audio tour company offering walking tours all over Greece (as of recently also in Italy and the Netherlands), called “Piraeus: Hidden Urban Stories”.

The tour starts in a spot near the port that’s more than familiar to me, one that I pass through on several mornings every week; the electric railway station. It isn’t the first station of Piraeus, though it is old. Designed by brothers Ioannis and Miltiadis Axelos and completed in 1929, it’s a miniature of Milan’s central rail station, with a dome and a glass ceiling.

I usually rush through. This time however, I take a look around, notice the architecture and the movements of all the people in a hurry (running, ducking to avoid the wings of pigeons, throwing arms out in aggravation over glitches in the new electronic ticket system) and then I press play.

A robotic English voice transports me to the year 1835, when the first regular communication between Athens and the newborn city of Piraeus was established.

It wasn’t trains.

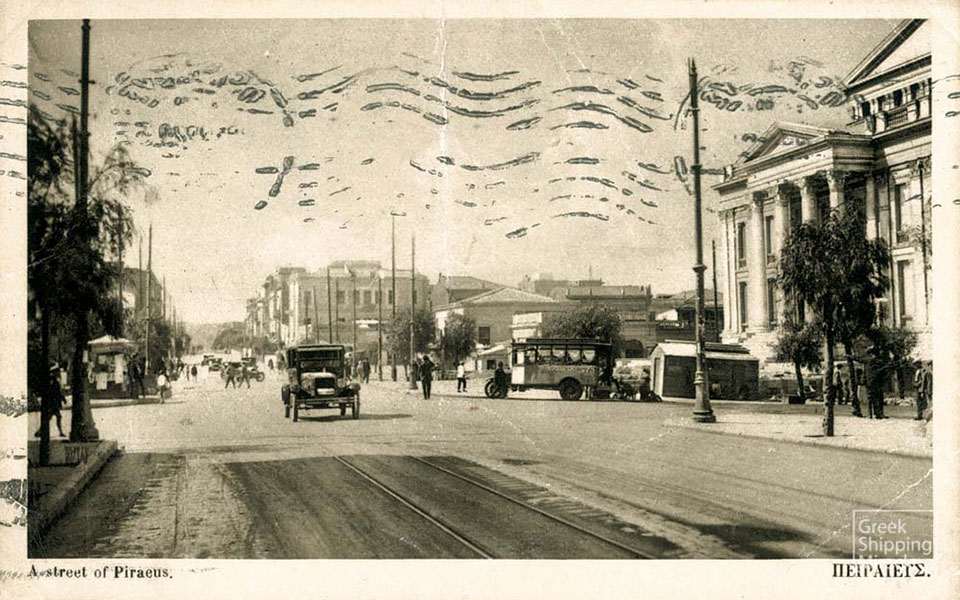

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

© Shutterstock

Once I get over feeling like I’m listening to Siri’s much more cultured English cousin, I can almost see it: In the 1830s, the road between Athens and Piraeus was constructed, and horse-drawn carriages began running back and forth between Athens and this location four times a day. The modern city of Piraeus was still in its infant years; pastures stretched out towards Athens and the bays of Pasalimani and Koumoundourou (known as and Mikrolimano today), but construction was going on everywhere.

It would take over thirty years before the first train would arrive in the city (in 1869). It came from Thiseio, and onboard was Queen Olga and Prime Minister Thrasyvoulas, along with other members of the Athens elite. By this time, Piraeus was already a bustling seaside city.

They built this city

Everything was planned. As the capital grew, there was a need for a functioning city near the port. The Greek government and the new Municipality of Piraeus, often led by the brothers Dimitris and Tryphon Moutzopoulos, who ruled Piraeus like a family business in the 19th century, did everything necessary to make it happen.

They were helped by well-trained architects and builders. The first architects to take on Piraeus were Stamatis Kleanthis and Eduard Schaubert – two graduates of the School of Architecture in Berlin, who created the underlying city plan. It featured a triangular shape, which the city has now outgrown, with a rectangular street grid, which hasn’t changed.

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

In 1836, the same year in which the road to Athens was constructed, a royal decree declared that the undeveloped public plots of half of the triangle (specifically, the ones on the right side of the Athens-Piraeus road), would be given to the refugees of Chios, whose homes had been destructed by the Ottomans in 1822. A few years later, an area near the port was put aside for 220 internal migrant families from Hydra. Other plots were sold cheap. The city needed citizens.

© Paulina Kapsali

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

I walk to the area that used to host the families from Hydra, to find what’s left of the Kleanthis storehouses. It is the oldest public building in Piraeus, completed in 1850. It’s in a ruinous state, partly demolished to make room for an office building, blackened by fires and looking so fragile, it seems best to observe it from across the street. A restoration seems unlikely, so I feel privileged to see it while it’s still standing.

The audio guide paints a picture for me again, reminding me that a century and a half ago, this building stood on the water’s edge. Today the sea is some distance away, due to the expansion of the quays.

© Clio Muse

Unlike the Kleanthis storehouses however, most of the buildings included on the tour are in excellent shape. The old post office from 1901, for example, now housing the Municipal Art Gallery of Piraeus, was renovated following the 1981 earthquake, and looks as good as new.

The towering Aghia Triada Church does as well, but as I learn, it’s not the original church. The original was destroyed in German bombardments in January 1944, killing many civilians who had sought refuge inside. It was rebuilt with money funded by a bus ticket surcharge.

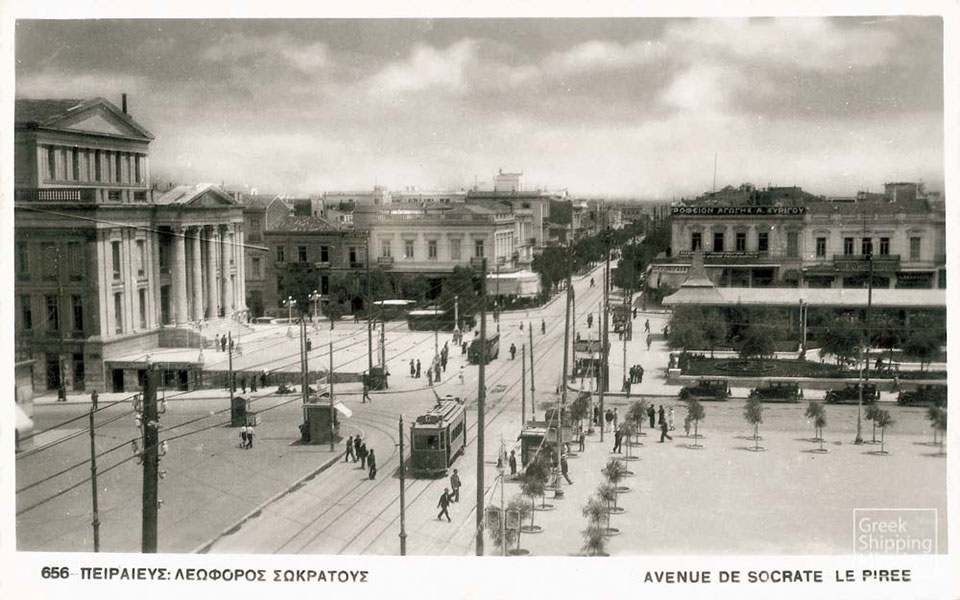

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

One of the most iconic landmarks of Piraeus, the Municipal Theater in Korai Square, designed by Ioannis Lazarimos, is as impressive today as it was first intended. However, for much of its existence, it’s been under construction or repair.

Tryphon Moutzopoulos, the city’s mayor in 1874-1883 and 1895-1903, dedicated over 60% of the 1882 public works budget to the project, but it wasn’t enough. The next mayor, Theodoros Retsinas, stopped all work due to financial difficulties, and the half-finished building was used for boat storage for years, before finally being completed with the help of architect Ernst Ziller, and inaugurated in 1895.

Various damage caused the theater to close for restoration work through the years that followed, and in 2008, it closed again for a five-year restoration project. Today, the theater is fully operational and open to the public. A brand-new café inside, Foyer Café Bistrot, decorated with vintage furniture to suit the style of the building, is now the talk of the town.

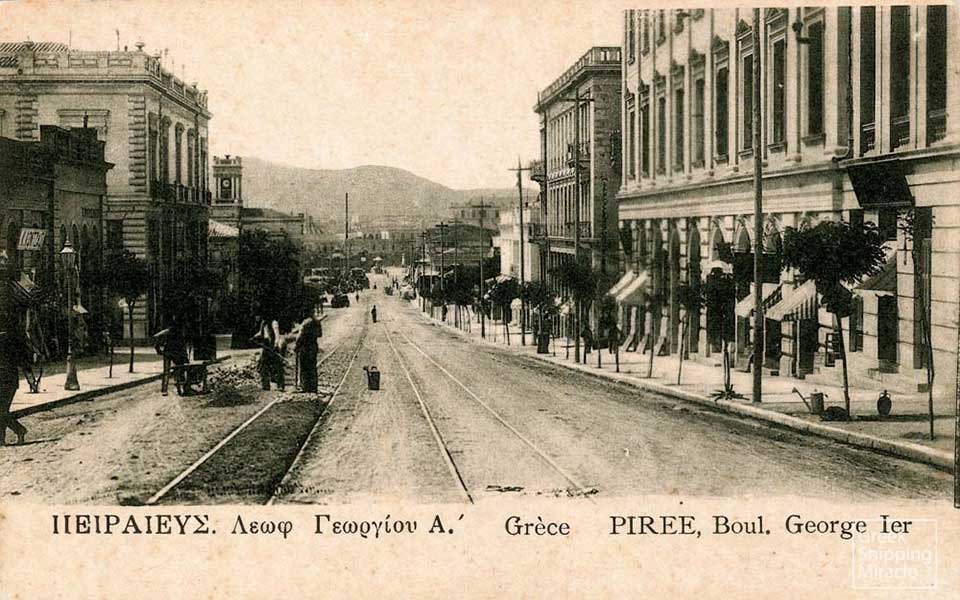

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

Outside the theater, on Vasileos Georgiou Street, another sight seems to echo the history of the city; new tracks, not yet in use, have been installed and will soon connect Piraeus to the coastal tramway. The old light railway, which existed here between the 1940s and the 1980s, ran in the other direction, connecting the city with the Salamis Naval Base.

© Greek Shipping Miracle online maritime museum - www.greekshippingmiracle.org

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

The neighborhood of mansions

The 19th century government efforts to build a city by bringing people to Piraeus wasn’t all architectural marvels. In the areas settled by poor immigrants and refugees, the homes built were very humble. Those houses, like the ones that used to surround the Kleanthis storehouses, didn’t stand the test of time. However, the new city also attracted a large number of temporary residents; wealthy people who spent their summers in impressive mansions and villas by the sea. Some of those homes still exist.

© Clio Muse

At Alexandras Square stands a yellow mansion designed by Ziller which, as I find out, is a survivor of what used to be called the Neighborhood of Mansions: seven impressive homes where royalty and elite spent their summers.

Ziller built them all towards the end of the 19th c, and kept one of them – a remodeled glass-factory with a freshwater well (a rare and impressive luxury at the time), as his summer home. It was here that he developed a relationship with the royal couple, King George I and Queen Olga, who stayed in one of the mansions for two summers, which led to him famously designing their palace at Tatoi.

Some of the stories told though my headphones are as gripping as gossip. For example: King George and Queen Olga had a daughter, Princess Alexandra, who married a Grand Duke of Russia. Suffering from a fall during her pregnancy with their son, she gave birth prematurely and died soon after, at the age of 21. Alexandra Square was designed in her honor. Her son, Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, went on to participate in the assassination of Grigori Rasputin.

Did you get all of that? Possibly the best thing about the audio tour is that you can press repeat as many times as you like. The English robot lady doesn’t mind. She also doesn’t mind you pausing to google for more information when you just can’t get enough. Turns out, Dmitri Pavlovich also competed in horseback riding in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, and dated Coco Chanel.

© Clio Muse

Later, standing in front of a building I thought I knew, having sipped plenty of coffees and glasses of wine in its courtyard when it operated as a clothing store and café a few years back, I see what I was ignorant enough not to notice then: Spyridon Metaxa’s coat of arms on the wrought iron gate. Metaxa, who founded the famous Metaxa distillation company, was the first owner of this mansion, which was also designed by Ziller and completed in 1899.

Many public institutions in Piraeus were also funded by private donations. The Rallis and Ioannides families funded the founding of two schools in the mid 19th century that survive until this day. I know them both. My father went to the Ioannides school, and my grandmother attended the Ralleio school for girls.

As I continue my walk towards the next stop of the tour, I’m curious to find out what other personal connection I might find to the stories of old Piraeus. Will the next stop be right next to my first apartment, or my regular bus stop? Will it be another neoclassical beauty I’ve admired a thousand times, never knowing it belonged to someone who helped build the city?

As it turns out, Piraeus, a place that grew from nothing to a town between the years 1834-1837, wears its history on its sleeve.