As ancient Athens moved away from kingship and Archaic-era tyranny during the 6th c. BC, formerly monarchial powers and duties were taken on by public magistrates, whose ranks eventually swelled to more than a thousand by the Classical 5th and 4th c. BC. Nevertheless, through family or tribe connections, political associations (hetaireiai) and social networking, often at symposia (upper-class dinner/drinking parties), the Athenian aristocracy maintained its hold on power.

In the face of rising popular anger over oppressive debt, increasing prices, inadequate representation and other perceived injustices, Solon proposed reforms in 594/593 BC that addressed all these issues and defined four classes of citizens (based on annual cereal production): the Pentakosiomedimnoi (500-measures), Knights, (300 measures), Zeugitai (200 measures) and Thetes (everyone else). He called for all citizens to participate in the Assembly (Ekklesia) and may have created the Council of 400 (Boule).

A second reformer, Cleisthenes, reorganized Attica in 508/507 BC into 10 geographically-based tribes, rather than four family-based tribes. He also increased the Boule to 500 members, 50 from each tribe, and established a more objective system of sortition for filling government positions and jury panels. To combat tyranny, Cleisthenes instituted ostracism.

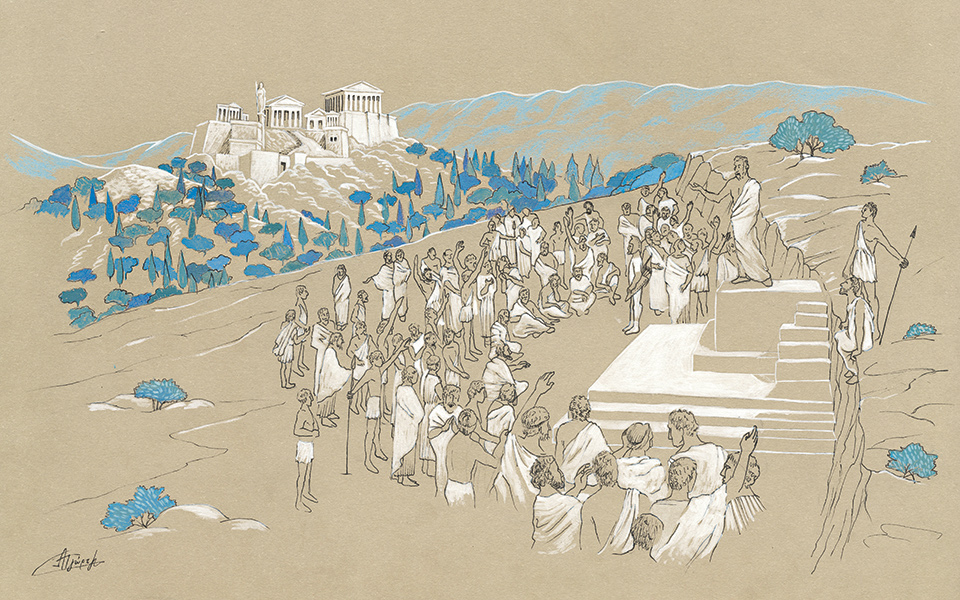

The Ekklesia met on the Pnyx Hill, where speakers stood on an elevated bema to address a gathering of citizens that usually numbered at least 6,000 and may on occasion have reached tens of thousands. As Classical Athens’ prosperity and population expanded, along with its domestic and imperial administration, the lowest class (thetes) became increasingly necessary (e.g., as naval rowers and sailors) and thus potentially powerful.

Pericles and other 5th-c. BC politicians understood this and frequently took steps to appease these ordinary citizens, often through largesse. Final decisions in Athens’ direct democracy were made by The People (Demos) in the Ekklesia — where some politicians saw the jostling crowd, with its evolving role and collective desire to be courted and entertained, as their own opportunity.

“In present-day terms, late-5th c. BC Athenians seem to have intentionally embraced leaders who were not “Washington Insiders” and not “owned” by traditional political groups.”

© Illustration: Anna Tzortzi

“Clever rhetoric and shocking conduct saved demagogues from having to spend years establishing respectable records of reliable military and political service, as Themistocles, Cimon, Ephialtes and Pericles had all done.”

PERICLES AND THE RISE OF DEMAGOGUERY

The golden era of Athens, from the mid-5th c. BC, was a time of artistic, intellectual and social achievement, but also of political backlash and fresh perspectives. We tend to think of the Periclean period as an apex in ancient Greek culture, but it was more the beginning of a great democratic experiment, still ongoing today.

Pericles represented a transitional, somewhat ambiguous figure, according to historian W. R. Connor*, who combined a traditional political approach with characteristics or methods more fully developed by the radical demagogues that followed him. After the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (431 BC) and Pericles’ untimely death (429 BC), civic problems multiplied.

The popular Ekklesia resembled more and more a boisterous mob; and the sharp rise of demagoguery accentuated a range of long-festering, as well as relatively newfound, Athenian political and social conflicts: aristocrats vs working-class; rich vs poor; privileged vs less advantaged; old reputable families, networked together vs The People; the “chrestoi” (useful, well-born citizens) vs the “phauloi” (simple people, lacking in politically influential friends); oligarchs vs democrats. In the late 5th c. BC, there also appeared questions of old money vs nouveaux riches and, in particular, traditional vs “new” politicians.

Pericles, although a wealthy aristocrat, followed in the pro-People/democracy footsteps of his great-uncle Cleisthenes. Like Solon, too, he profoundly changed the social, political and economic life of the average Athenian citizen. In the 450s and 440s BC, he further weakened the supreme Areopagus court; brought more citizens into the state’s political and judicial processes by introducing payment for service; made the two lowest classes eligible for the archonship; subsidized poorer citizens that wished to be knights; reduced unemployment by hiring state-paid workers; constructed an odeon (music hall); and gave every citizen two obols annually, to spend on public entertainment and festivals.

Pericles also elevated the status of Athenian women; encouraged intellectual and artistic achievement; and beautified the Acropolis with new temples and a monumental gateway — a measure described by Plutarch (1st/2nd c. AD) as “the one…which…gave the greatest pleasure to the Athenians, adorned their city and created amazement among the rest of mankind…”

Under Pericles, the courtship of the Athenian Demos had begun. In 424 BC, the Old Comedy playwright Aristophanes (Knights, 1340) alludes to the use of love terminology by Cleon, Pericles’ successor and the first true demagogue, during addresses to the Ekklesia in which he proclaims: “Oh, Demos, I am your ‘erastes’ [lover]…” Such erotic vocabulary was indeed utilized by Athenian orators, writes Victoria Wohl**, especially by demagogues, but Pericles had already hinted at the practice in his famous funeral oration (431/430 BC) when he directed the assembly to “daily gaze upon the city’s power and become lovers [erastai] of it” (Thucydides 2.43.1).

EXPLOITING THE POWER OF THE PEOPLE

Athens in the late 5th c. BC was a city at war. And wars, as we know too well today, bring change and encourage extremism. Troubled times also offer opportunities and can lead to more overt demonstrations of the power (and weakness) of The People.

Ambitious Athenian politicians, Connor argues, many of them young and seeking a fast way to the top, understood that “the reward would be great if means could be found to activate and organize the phauloi, the ‘unpretentious’ citizenry. Herein is the origin of a new kind of democracy, a new pattern of politics that was to become increasingly conspicuous…”

A host of flamboyant, “new” politicians appeared in the post-Periclean era, including Cleon, Alcibiades, Cleophon, Syracosius, Hyperbolus and Anytus. If Old Comedy is to be believed, the demagogues were often known by colorful nicknames such as Bleary Eyes, Smoky, Hempy or Quail.

In reflection of their livelihoods, Cleon was The Tanner, Cleophon The Lyre-maker, Lysicles The Cattle-dealer and Eucrates The Flax-merchant. Anytus, one of Socrates’ accusers, was also a leather-tanner. Alcibiades was admired for his charm and striking handsomeness. Sometimes their very names became proverbial expressions: “Beyond Hyperbolus” implied someone extremely litigious.

To make their rhetorical points, demagogues often used inflammatory language and theatrical behavior. Aristotle reports that Cleophon “made a dramatic entrance into the assembly with a speech ready against peace negotiations and his breastplate girded on…” The more obscure Syracosius is portrayed in Eupolis’ comedy as “running about the bema yelping like a hound dog.”

Demagogues made grand shows of emotion and empathy, so as to connect with ordinary citizens on a visceral level, and won additional favor acting as The People’s governmental informants.

Through their outrageous language and behavior the demagogues broke away from traditional, conservative ways. They renounced the usual political ties (as Cleon showily did; Pericles more discreetly before him) and may not have objected much to comedic, occupation-related epithets (or accusations), as they would have benefited from appearing more working-class.

In reality, many demagogues were high-born and affluent. Alcibiades, Plutarch observes, had everything necessary to be an Old School politician, but preferred to be a demagogue.

“We tend to think of the Periclean period as an apex in ancient Greek culture, but it was more the beginning of a great democratic experiment, still ongoing today.”

© Illustration: Anna Tzortzi

FAME AND FORTUNE

The primary incentive for adopting a demagogic approach was the political shortcut it provided to fame and fortune. Clever rhetoric and shocking conduct saved demagogues from having to spend years establishing respectable records of reliable military and political service, as Themistocles, Cimon, Ephialtes and Pericles had all done.

In the demagogic era, Nicias and Alcibiades were also generals, perhaps also Cleophon and Hyperbolus, but Cleon had to be publicly cornered before he would take command (aided by a real general) and deal with the Spartans trapped on Sphacteria Island in 425 BC.

Many demagogues were prosperous businessmen who viewed government and popular politics as a means to further increase their wealth. Isocrates writes, “these men…dare to say that their concern for public affairs prevents them from attending to their own business; but it appears that their ‘neglected’ affairs have made greater gains than they would have ever thought to pray for.”

A BAD REPUTATION WELL DESERVED?

Athenian demagogues received a lot of “bad press” but was the heavy criticism deserved and accurate?

In an increasingly elaborate and divisive government, notes Connor, Athenians “needed…a new breed of specialized, semi-professional politicians, who could master and explain the complex details of their city’s business.” Competent, well informed demagogues such as Hyperbolus helped the common citizenry to see behind the oligarchic curtain of traditional politics.

Aristotle accuses Cleon of shouting and dressing improperly, but in conservative Athens even his use of hand gestures while speaking was considered unorthodox and vulgar. Thucydides and Aristophanes were also sharp critics, but the historian was an ardent Pericles supporter and both men had previously suffered prosecution by Cleon. Besides, as today, politicians were fair game for writers of parody and satire.

Aristotle writes “As long as Pericles was the leader of the people, the state was still in a fairly good condition, but after his death everything became much worse. For then the people first chose a leader who was not in good repute with the better people…” However, in present-day terms, late-5th c. BC Athenians seem to have intentionally embraced leaders who were not “Washington Insiders” and not “owned” by traditional political groups. The crime of many demagogues appears to have been that they came from the “wrong” families, those not traditionally connected or politically active.

In the end, demagoguery — ancient or modern — is all about exploitation, and therefore must be guarded against. The ancient demagogues were a sordid group that thrived on turmoil and social division. Cleon openly sowed distrust of intellect, claiming that “states are better governed by the man in the street than by intellectuals…who… want to appear wiser than the laws…and…often bring ruin on their country.”

Demagoguery in Athens was also risky and vengeful. Hyperbolus was ostracized ca. 416 BC; Cleophon was ultimately removed from power and executed in 404 BC on a trumped up charge; and Anytus was likely motivated by Socrates’ personal attacks when he contributed to the philosopher’s prosecution and death in 399 BC.

Positive and negative lessons can be learned from ancient democracy, especially today when democracy internationally is again under attack — with a decline in the free press, often violent suppression of dissenting voices and a troublingly widespread return to the worst sort of demagoguery.

“In the late 5th century BC, there also appeared questions of old money vs nouveaux riches and, in particular, traditional vs “new” politicians.ans.”