Stubbornly, I clear my mind of the image of the island parading across the lists of the best party destinations in the world and instead embark on my trip to Mykonos guided by modernist architect Aris Konstantinidis’ (1913-1993) book, Two ‘Villages’ from Mykonos. Throughout his career, this profound thinker focused on the essential element of architecture: the relationship between the building and its surroundings. Thinking about this, I feel some anxiety as I approach Mykonos, but even though intense residential development has compromised in places the natural contours of the landscape, I can still see traces of the island he describes: “Stones that were so bright from afar, and that you thought were strewn here by the Great Maker of the world, prove from up close to be nothing more than loving, small and innocent buildings, the work of man in the zeal of his daily toil.”

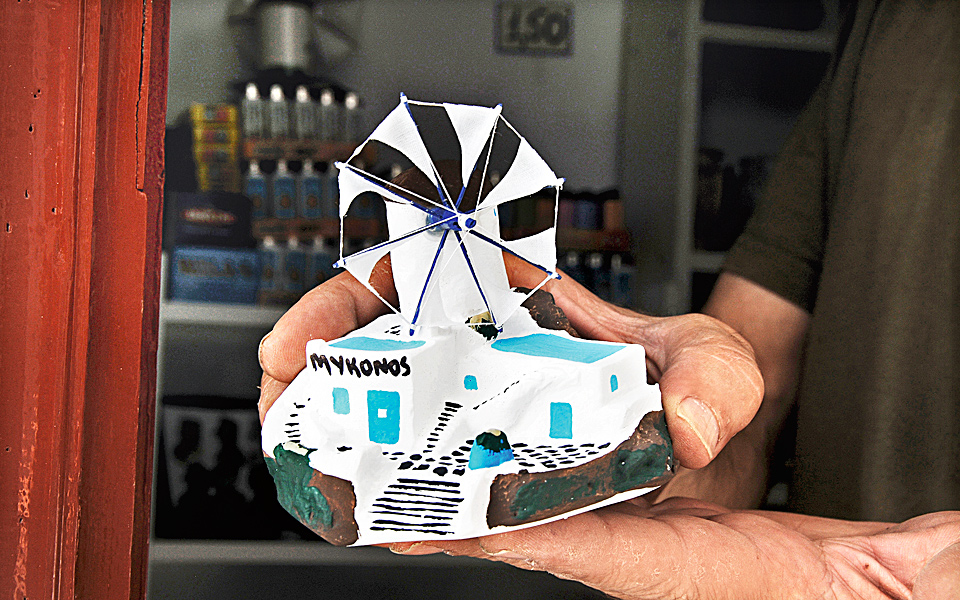

It is such “small and innocent buildings” that make up Chora, the capital and center of island life for locals and visitors alike. Built along the coast in order to facilitate maritime commerce, Chora is sheltered by two small hills, one topped by the castle and the other by the island’s iconic windmills. As is the case in all the capital towns on Cycladic islands, the charming architectural composition of houses arranged along narrow maze-like streets is an invitation to any explorer. The difference is that here, instead of wandering along quiet cobbled alleys admiring the shadows cast by the harsh island light, or enjoying the dramatic views as you would in any other Cycladic castle-town, you find yourself in the middle of an open-air shopping mall of chic boutiques, trendy galleries and pricy jewelers.

“I duck into alleys looking for snapshots of daily life: a bustling home, a family out shopping, two children playing. It’s not as easy as I think, as the crazy number of shops means that the only spaces left for residents to congregate are a few public squares and church courtyards.”

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Many big fashion houses are here: Hermes, Dolce&Gabbana, Ferragamo, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Dior… I can almost hear my credit card sighing in my purse. I resist all temptation until I am drawn, as if by a magnetic force, to a pair of children’s shoes in a shop window. More artwork than footwear, they cost three times more than I would usually consider spending. My resolve crumbles as my cosmopolitan surroundings convince me that I, too, can be part of the elite that makes such a purchase without blinking. I’m not even sure if I’m buying the right size. I snap out of this shopping trance as I trip on my way out of the shop, catching my foot on its entrance step. I look down and see a beautifully crafted slab of marble, a fine piece created by some anonymous local artisan.

I look back, and this time I’m noticing the wonderful building that houses the store. The red shutters and window frames, the wooden door, the stone staircase leading to the upper floor indicate that this was once someone’s home. The changing room was probably the dining area where the family gathered for lunch. In the adjacent building, now a bar, I imagine a child’s bedroom in one corner and, through the front window of the jewelry store two doors over, I can see the housewife who, half a century ago, stood patiently scrubbing her laundry right where the display cases are now.

I silence the little voice telling me to shop on and I start walking, this time to get a proper look at Chora, an architectural wonder that prompted Le Corbusier to claim during one of his trips to Greece that: “Unless you have seen the houses of Mykonos, you cannot pretend to be an architect.” There is little doubt that this is among the most impressive towns in the Aegean, with its two-story houses and their simple yet elegant external staircases, the cascades of bougainvillea and pots of geraniums adding yet more color in the bright light, all while basil discreetly perfumes the air. The simplicity of the white walls give them an almost plastic quality, a softness that creates a sense of interminable movement.

“More artwork than footwear, they cost three times more than I would usually consider spending. My resolve crumbles as my cosmopolitan surroundings convince me that I, too, can be part of the elite that makes such a purchase without blinking.”

© Perikles Merakos

© GettyImages/IdealImages

© Penelope Massouri

I duck into alleys looking for snapshots of daily life: a bustling home, a family out shopping, two children playing. It’s not as easy as I think, as the crazy number of shops means that the only spaces left for residents to congregate are a few public squares and church courtyards. I recall the words of Mykonian writer Melpo Axioti, an early 20th century intellectual force, and I get goosebumps remembering her prophetic words: “The island’s soul tries to burrow into an ever-condensed space, constantly being frightened off with the threat of death… and everything, but everything, is for sale.” If you want to know how many shops open in Chora every year, just count the number of deaths, a local tells me cynically: an older person dies, a house is closed down, a shop opens – that’s the cycle of life here.

There’s no denying that it’s a challenge to maintain a home in Chora. The money being offered for rent or purchase of property from businesses eyeing a piece of the tourism pie – which last year brought in estimated revenues of €14.2 billion throughout Greece (with Mykonos being one of its main money-making machines) – is hard to resist. Another problem is that the significant rise in the standard of living brought about by this tourism has prompted many Mykonians to built bigger, more comfortable homes with more amenities out in the countryside, usually on a family-owned plot of land, so there’s no incentive for them to continue living in Chora.

THE RELIGIOUS FACTOR

The most famous church in Chora is Panaghia Paraportiani, located on the edge of the Kastro neighborhood, near the castle. Considered a jewel of folk architecture, the structure is, in fact, five separate churches joined together. There are another 80 churches in the area, most with unexceptional interiors that belie some of the wonderful icons within, while marble plaques – both old and new – provide the visitor with significant historic details. A group of these churches are built in a row, one next to the other, earning them the nickname of “The Gossips,” because from a distance they look like local ladies gathered together to share comments on the latest village scandal.

© Dionysis Kouris

© Elena Paraskeva

© Dionysis Kouris

“It’s not as easy as I think, as the crazy number of shops means that the only spaces left for residents to congregate are a few public squares and church courtyards.”

I wander around the neighborhood of Lakka, away from the high street, and it dawns on me from an examination of the laundry hanging out from the window and balconies – always a good indication of people’s backgrounds, economic status and habits – that many of the residents of Chora are not locals, but migrant workers, both permanent and seasonal, feeding the voracious tourism machine.

I finally come across some locals hanging out at Giora’s Bakery. This establishment is a living monument, active since the 17th c., right below the windmills on the hill that once supplied flour to the islanders and to passing ships. Today, it serves coffee to the older folk at a handful of tables and continues to supply traditional bread to residents who will invariably stop for a chat. It is also a favorite among tourists looking for an authentic experience. The baker’s wife, Chloe Papaioannou, tells me that they only started offering coffee when tourism started to pick up, and that they serve local delicacies like soumada (orgeat syrup), almond cakes and other products from small-scale local producers. Not a Mykonian herself, Chloe describes how she came to fall in love with the island back in its last throes of innocence. “It was the summer of 1989, and I came in on the afternoon boat. I sat down on some stairs waiting to meet a person about a job, and I promptly fell asleep. When I woke up, there was a small tray next to me: on it was a Greek coffee, a small plate of fruit preserve and a glass of water. An old lady dressed in black was sitting beside me, watching over my bags.”

© Penelope Massouri

© Evelyn Foskolou

“What about now?” I ask her. Could such a thing still happen? She just shrugs. I follow the locals to their next stop, the small market they call Banga just before the Town Hall (easy to spot thanks to its distinctive red-tile roof) in Gialos, where fishermen sell the catch of the day on marble benches and about a dozen farmers display fresh produce: bright red tomatoes, cucumbers, fragrant melons and juicy watermelons; whatever they can get to grow on this arid, rocky island. The farmers, too, are struggling to resist the siren song of tourism development. Their fields, they explain, are worth so much more as residential or commercial property, and who wants the toil of farm life when you can have money in the bank instead? Across the street, the cafe-ouzeri Bakogia is like a vortex that has successfully obliterated all traces of modern Mykonos: the lounge sofas, the foreign hors d’oeuvres, the sun loungers that evoke fancy hotels and the sexy beauties swaying their bikini-clad bodies to the latest beats, they’re all conspicuous by their absence. I sit for a proper ouzo and nibble on mostra (rye rusks sprinkled with olive oil and topped with diced tomatoes and fresh, white kopanisti cheese). When winter comes and the island’s streets start to empty, this little cafe will still be open for the handful of Mykonians who live here all year round, another point of resistance against the transformation of Chora into a residential ghost town ripe for commercial exploitation. It is getting on towards late afternoon when I return to the center of the town, this time more confident about exploring its unnamed alleys.

“When winter comes and the island’s streets start to empty, this little cafe will still be open for the handful of Mykonians who live here all year round, another point of resistance against the transformation of Chora into a residential ghost town ripe for commercial exploitation.”

© Efi Paroutsa

© Pola Kouri

© Courtesy of Moni

In Matoyiannia, I peek through the open window of a neoclassical residence. Though somewhat incongruous amid the vernacular architecture, its beautifully adorned ceilings and period furnishings impress me, as does the owners’ apparent ability to put up with the noise and foot traffic all summer long. I stroll past the only oasis of green in the town, the open-air cinema Cine Manto, and stop at Lena’s House, a small museum, to learn more about the island’s folk traditions and about the local women who played such pivotal roles in island history. Foremost among them is Manto Mavrogenous, a woman who roused her fellow islanders to fight during the Greek War of Independence and who sacrificed her fortune to fund the war effort. The Aegean Maritime Museum is located right next door; a lighthouse from 1890 stands in its courtyard.

As dusk descends, the streets have become so crowded that I feel as though I’m standing in a supermarket checkout line at closing time. I look for a way out of the throng, but I’m completely disoriented. Where’s the sea? Every 10 meters or so, I stop and ask the way to Little Venice. As I finally reach the shore, the strong northerly wind known as the meltemi blows everything away and clears my head. I sit down at Caprice and look across at the row of captain’s houses that feature on so many postcards and in so many articles on Mykonos. Straight ahead, there’s the vastness of the sea. The sun is starting to set, but the island is not about to slow its tempo just because it’s getting dark. Quite the opposite; the music gets louder, as I dive back into the river of humanity looking for that tiny part of Mykonos that corresponds to me.

I embrace the “Manhattan of the Aegean”, ready to burn the midnight oil with this insomniac town, keeping it company through the night. When the last night owls stumble out of the bars at dawn and I head for my bed, the shops will be opening their doors again, welcoming the early birds from the latest cruise ships to arrive – but sleepless Mykonos will not have had a moment to catch its breath.

“I embrace the “Manhattan of the Aegean”, ready to burn the midnight oil with this insomniac town, keeping it company through the night. “