Brice Marden’s huge studio on the small Saronic island of Hydra is bathed in sunlight. The top floor of the elegant old townhouse has always been dedicated to work and was where sails were made for the building’s original shipbuilding owners, the Kriezis family. The American artist, who shares his time between Hydra and New York, made it his studio in 1993.

He was not there at the time of our recent visit, but his presence was powerful in the simple space: tools, paints and other paraphernalia are scattered across a long wooden workbench and an old sofa reclines in one corner, surrounded by just a handful of objects, as the midday sun washes across the stripped wood floor and white walls.

© Paris Tavitian/Museum of Cycladic Art

A painting leans against one wall, long unfinished, says Dimitris Antonitsis, an artist and close friend of Marden and his wife Helen, an ideal guide for our visit to the house. I can’t imagine what is missing from the painting – it seems so whole.

Marden would not agree. He is often known to wrap up a day’s work by painting the entire surface of a piece in a single color and starting over on the basis of a photograph of the previous composition. He thinks of art as a vehicle that transports the viewer, and abstract art in particular as being more open to the viewer and the real world, but without telling you what it is you ought to be seeing.

© Paris Tavitian/Museum of Cycladic Art

© Paris Tavitian/Museum of Cycladic Art

This is his way of approaching abstraction. Marden is widely regarded as one of the most influential representatives of American abstract expressionism, a member of a dynamic generation that emerged in New York in the 1960s and left its mark on late 20th century contemporary art. And at 83 he remains true to the vision that has shaped his work from the early monochromatic days when he used a kitchen spatula instead of a brush to the more recent compositions of black-and-white calligraphic shapes that he paints with sticks and twigs, which are much in evidence in the Hydra studio – humble tools put to work beside expensive Kremer pigments bought in New York. He collects these sticks on his walks around the island and uses them to create these paintings, these shapes that seem like a mere gesture at first glance, fluid lines that are worked again and again. As for his geometric work, he once remarked that the square must be the greatest invention ever made by humans and that every one of his squares demands a very specific color that he spends a lot of time and energy trying to achieve.

Everything about painting, he says, is about light, and perhaps this is what attracted him so strongly to the Greek island back in the 1970s. Bohemian and cosmopolitan, he has been anchored fast to Hydra since and stays in touch with his local friends and the island’s significant community of artists, not to mention the influence it has on his work.

© Paris Tavitian/Museum of Cycladic Art

In an old wooden cupboard in the house that he has kept almost exactly as it was when Eleni Kriezi lived here with her husband, he keeps a collection of postcards with ancient Greek art, the kind sold at museums. Greece is brought into sharp focus in Marden’s work as he explores familiar elements that he feels connected to.

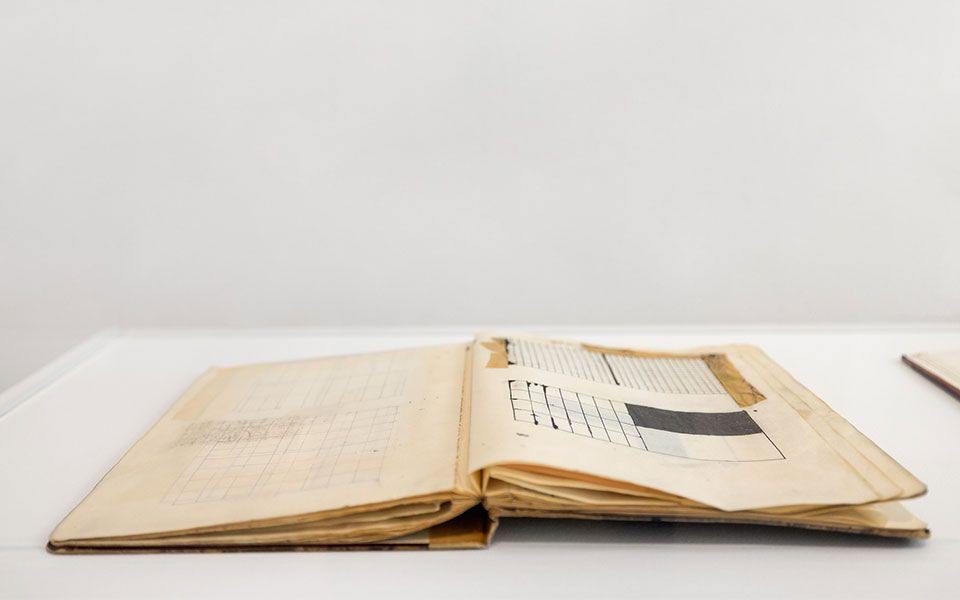

Now, the Museum of Cycladic Art is showing a selection of these pieces that are inspired by the metaphysics of ancient Greek heritage as part of its “Divine Dialogues” series. Paintings, drawings and notebooks are positioned beside antiquities selected from the museum’s collection in an invitation to the viewer to ponder the artist’s visual vocabulary.

The exhibition also includes three new pieces by Marden in marble, as well as a series of drawings inspired by the waves on the sea of the Saronic Gulf which are being shown for the first time.

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.