It was Christmas of 1954 when 17-year-old Stefanos Sinos visited Mystras for the first time, in the company of two schoolmates. He had already decided he wanted to become an architect, and he was enchanted by the ancient and medieval monuments of his homeland. What he found on the site of the Late Byzantine fortified town, and particularly at the Palace of the Despots, left him speechless. “I saw an entire palace, in a state which seemed to me wild and dangerous,” he says.

He remembers that he stood in front of the monument to have his picture taken by his friends, but his mind was racing. “I didn’t know who had restored the palace,” he continues. “Later, when I became a professor, I met Anastasios Orlandos, who had undertaken the restorations of 1937-39, and he explained how he had preserved the monument. In the intervening years, however, there had been damage due to weather. Having visited the place many times over the years I decided that something had to be done. I thought, the palace cannot be left in this state.”

Villehardouin

More than seven centuries ago, in 1249, a few decades after the first sacking of Constantinople by the Crusaders, William II Villehardouin, the Frankish Prince of Achaea, built the fort known as “Myzithras” on the hill of the same name at Mystras, to defend the Evrotas Valley from attacks by the Serbs. Lower down the hill, he erected a structure which he used as his residence when visiting the region. In 1259, however, William was defeated by Michael VIII Palaiologos in the Battle of Pelagonia, and in 1262 he agreed to surrender the castle, among other possessions.

For the ensuing two centuries, Mystras was the capital of the semi-autonomous Despotate of Moreas, whose first ruler was Manuel Kantakouzenos; the settlement would emerge as a major economic and spiritual center of the late Byzantine empire. It is around this time that construction on the Palace of the Despots began, centered around the original residence built by William but with the addition of new wings to house residents or accommodate administrative functions. The palace was at its most glorious in the early 15th century, when its splendor reflected the Palaiologos dynasty’s attempts to reorganize the empire. It was at this time that a throne room was created in the west wing.

© A. Orlandos archives

© The G. Millet archive

Even before he began his restoration efforts on the palace, Stefanos Sinos knew all of this. Having served as assistant to the Chair of History of Architecture at the University of Karslruhe in Germany, he returned to Greece where, in the early 1980s, he was a professor of architecture at the National Technical University of Athens. It was during this period that the general secretary of the Archeological Society of Athens, George Mylonas, informed him that President Konstantinos Karamanlis wanted to support the restoration of a Byzantine fortress in southern Greece to complement the excavations of Manolis Andronikos in Macedonia.

Sinos explained to Mylonas and Karamanlis his views on the potential for restoring the monuments of Mystras and, in early 1984, he met with Culture Minister Melina Merkouri as well. They all agreed that the work should proceed. A working group for the project was created that year. In addition to carrying out preliminary studies, the group organized a major international conference at Mystras.

The restoration work took many years to complete. Most of it was carried out between 1990 and 2015, with Stefanos Sinos presiding over the scientific committee which succeeded the working group. His contact with Konstantinos Karamanlis continued, albeit through correspondence. “After that first meeting, I never met with him again, but every year I sent him a written progress report,” Sinos remembers. “He always wrote back, sometimes with a touch of humor, and usually with phrases like, ‘Bravo, continue!’.”

© Kapon Editions

The Book

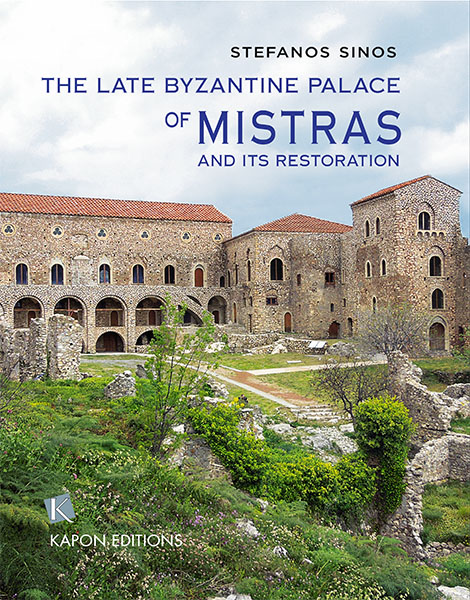

Kapon Editions recently published the book “The Late Byzantine Palace of Mystras and Its Restoration,” which Stefanos Sinos completed in the course of this past year, during lockdown. He chose to write it in English in order to address the international scientific community. It presents the most detailed presentation of the architectural history of the Byzantine Palace of the Despots, its original remains, the studies done, and the restoration works and the techniques used, all recorded in a rich photographic archive. Although the character of the publication is largely scientific, Sinos is able to explain the principles of his work and his original vision with the same enthusiasm which seized him during his first visit to the monument.

“It is the only Byzantine palace which has been preserved in its entirety. There is nothing in Istanbul which has been preserved, as this has, over three floors,” Sinos tells us, adding, “it could easily become accessible, so that visitors could better understand the life of an emperor or his heir-apparent. It is a building which is crucial to the history of this country. However, I also wanted to highlight the Western architectural influences on the palace. What were these? They certainly weren’t just any Gothic influence; they were the Venetian version. The windows in the east wing, which was built by Manuel Kantakouzenos, are identical to those recorded in Venice in the 19th century by the English art historian John Ruskin. It is not a coincidence that Manuel traveled frequently to Italy.

“What’s more, after Kantakouzenos, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos signed the unification of the two Churches at the Florence Synod. The attempts at unification can be seen in the later wings of the Palace, with the introduction of Gothic elements in the Venetian style in the window design. This is something which had not been previously observed, but I believe I have demonstrated it to a satisfactory degree.”

The throne room and the surprise of the Emperor’s seat

It is remarkable that, along with the rest of the palace, the throne room in the west wing has survived nearly intact. Sinos finds one element of this room particularly charming. “The emperor is not seated at the top of the hall, on the narrow end, as we imagine with kings, being approached by their subjects at the end of a long room,” he explains. “On the contrary, he is seated halfway along one of the long walls, placing him in the middle of any gathering. The other participants do not stand, but are seated on benches at either side of their ruler. It indicates something perhaps beginning to resemble a more democratic relationship between the ruler and his officials.”

It is just such aspects of palace life that Sinos wanted to highlight in his exhaustive work. One question arising from the project has to do with the limits of restoration. Are the damages and the ravages of time not part of the building’s history? Might downplaying them create for us a problematic relationship with our glorious past?

“Time and its passage can be clearly seen. It is easy to discern the original elements from the new parts,” Sinos responds. “But beyond this, of course, there are limits and, in many cases, I am against complete restorations. You need to achieve a balance. We can’t always put things back as they were in the past because, in many cases, we don’t have enough information; we would be creating something fake. But some monuments have a great role to play in helping us understand our history, and where we have enough evidence, it is worth making the extra effort.”

In the case of Mystras, we are dealing with a UNESCO World Heritage site. The latest phase in its restoration (according to an announcement by the Ministry of Culture) will be completed in 2023, and will offer visitors a unique experience, presenting palace life with the help of new technologies.

Sinos worries that his age will prevent him from visiting the monument which moved him so deeply at 17; he also feels that a little more work is needed, work which he did not have time to complete. Nonetheless, he does not feel bitter about this, and is certain that the ministry will find the funds to complete the project.

Was there any part of the restoration that caused him particular concern during the work? “I was absolutely convinced that, in the throne room, there was another ceiling below the wooden roof,” he notes. “I didn’t include it in the restoration because recreating it would have depended too much on imagination, but the beams in the room do indicate its existence. We also know from descriptions by Bessarion of Trebizond [a 15th-century scholar and religious figure] that there was a ceiling below the roof of the palace at Trebizond, but I didn’t feel I could rely solely on this piece of evidence. It was a question which kept me awake at night.”

This article was first published in Greek on kathimerini. gr