Healthcare represented a primary concern for people of the ancient world, just as it still does today, but until the 6th and 5th centuries BC healing was rooted mostly in religion and magic. When people became ill or suffered injuries, they did not visit hospitals or clinics, but often sought out treatment and comfort from priests, offered sacrifices and prayers to certain gods, or consulted learned practitioners who might prescribe the use of medicinal herbs or the following of other, sometimes more mysterious, traditional rituals.

A MORE HUMAN FACE OF HEALING

With the emergence of the divine healer Asclepius, first mentioned in the 7th/6th c. BC texts of Homer and Hesiod, the infirm found a new champion, a figure usually depicted as bearded, mature and fatherly, like Zeus, and highly knowledgeable in medicine – like his own reported father Apollo – but more ordinarily human, more approachable and seemingly more genuinely concerned with the human condition. He usually carried a staff or walking stick and kept around him a snake and a dog as companions or sacred symbols.

Where deities including Eileithyia (the Cretan/Minoan goddess of childbirth and midwifery), Apollo and his sister Artemis, or mythical creatures such as the centaur Chiron (Apollo’s foster son, Asclepius’ teacher) had previously been main mythical sources of medical skill and solace, Asclepius came to represent the new generation, at a time in Classical Greek history when knowledge of medicine and the practice of health care were becoming more scientific endeavors. It was only with Asclepius that more formal “hospitals” were established. As his cult spread, sanctuaries dedicated to the healing god sprang up throughout many areas of the known Mediterranean world.

“Jungian scholars have suggested the dream healing therapy practiced at Epidaurus and elsewhere represents the early forerunner of modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy.”

© Italian School / Private Collection / De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

ORIGINS OF ASCLEPIUS

Asclepius originally appeared in ancient Greece at ancient Trikka (modern Trikala) in Thessaly. Trikka was considered his birthplace, from which, according to Homer, his sons Machaon and Podalirius traveled with the Greek army to fight at Troy. The Roman geographer Strabo reports that Trikka was the site of Asclepius’ oldest, most famous sanctuary. Two other major centers were Epidaurus and the island of Kos. The cult of Asclepius may have reached Epidaurus by ca. 500 BC and a later local tradition suggested that he had been born there, rather than at Trikka. Epidaurus became the main, highly influential base from which numerous other Asclepieia were founded — usually through a ritual in which a statue of the god or one of his sacred snakes was ceremonially transported to the prospective site and bequeathed to the new sanctuary during its dedication rites. Kos, too, became known for Asclepius in the 5th c. BC. His famous multi-tiered sanctuary there began to rise after the mid-4th c. BC.

EXPANSION

The 5th and especially 4th centuries BC were a time of great expansion for Asclepius, as his sanctuaries also appeared at sites including Athens, Corinth, Sicyon, Tegea, Megalopolis, Argos, Sparta and Messene. Asclepieia were also founded on the islands of Paros, Aegina and Crete (at Leben, a port of Gortyn); at Pergamum in Asia Minor, Alexandria in Egypt and Cyrene in Libya; as well as in the West at Rome — where the god occupied Tiber Island and was called Aesculapius. Altogether, hundreds of large and small Asclepieia were established in ancient Greek and Roman times, with almost every big town seeking to provide what was essentially a health-care facility for its residents and neighbors. Asclepius’ cult spread usually thanks to the well-intending actions of individuals and became increasingly popular because it appealed to individuals and reflected a growing interest in more reasoned, humanistic approaches to medicine.

Asclepieia functioned as sacred hospitals, nursing-homes, centers of religious worship and of popular entertainment, as well as gathering places for teachers and students, especially those interested in becoming doctors. Followers of the pioneering physician Hippocrates (ca. 460-ca. 370 BC) taught medicine at Kos, while the Roman doctor Galen (AD 129-ca. AD 200) received training at Pergamum before assuming his duties as personal physician to the emperor Marcus Aurelius.

© Drawing: Marina Roussou

EPIDAURUS

Sanctuaries of Asclepius shared many common characteristics. In addition to Asclepius, other health-related deities were also regularly worshiped in or near these places, including his father Apollo; his “aunt” Artemis, his sons Machaon and Podalirius; and his daughter Hygieia — the personification of health, cleanliness and hygiene. The 2nd c. AD traveler Pausanias records that, as a child, Asclepius was nurtured by a goat and protected by a dog — thus explaining why no goat sacrifices were allowed at Epidaurus, but dogs were a common sight generally in Asclepieia.

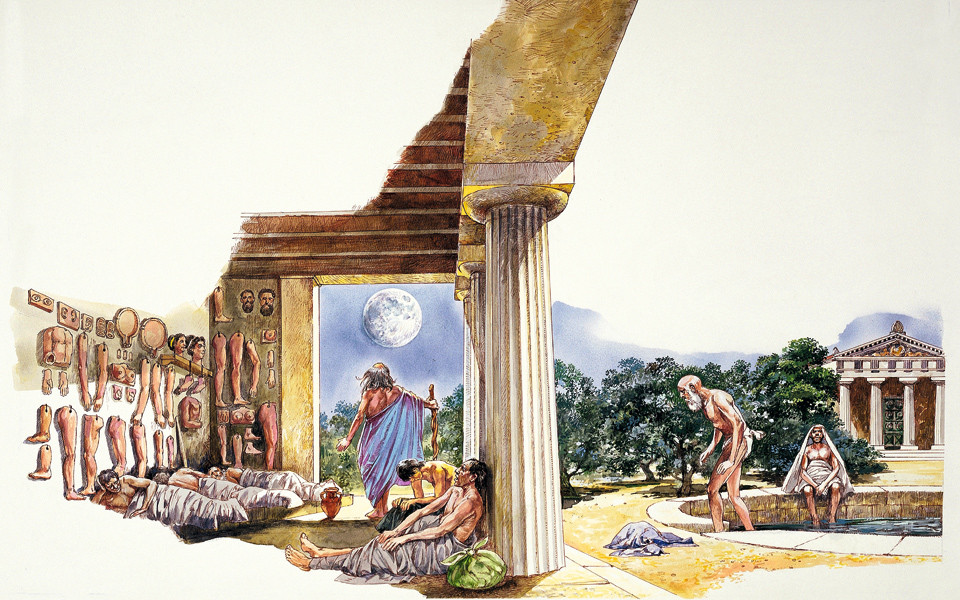

Besides altars and temples, another distinctive, colonnaded building of central importance (the Abaton) was provided, in which patients arriving at the sanctuary would undergo enkoimesis (incubation), spending the night there and waiting for the god to come to them in their dreams with a proposed course of therapy. At the exemplary site of Epidaurus, visitors also had access to bath complexes, a large dormitory-like hostel (Katagogion), ceremonial dining rooms, a stadium, a palaestra, a large gymnasium and a theater that would eventually seat more than 12,000 spectators.

A distinctive circular structure (Tholos or Thymele) near the colonnaded Abaton and the Temple of Asclepius may have housed the god’s sacred snakes, which embodied ideas of rebirth and rejuvenation. In some Asclepieia, non-venomous snakes were allowed to slither about freely on the floors of the visitors’ accommodations, while at Epidaurus the serpents, including a peculiar yellowish variety, were tame, according to Pausanias. The snakes in the Asclepieion at Alexandria were said by Aelian (ca. AD 175-ca. 235) to be gigantic, some reaching 6-14 cubits (about 3-6m) in length.

Springs, wells and reservoirs were also common features in Asclepieia. A sacred well inside the Abaton at Epidaurus served in the visitors’ purification process, prior to incubation. Following these two initial stages of treatment, actual medical therapies were often provided. Testimonials describing the frequent miraculous cures achieved at Epidaurus were inscribed on a series of stone slabs publicly displayed in the sanctuary. These fascinating accounts, which record the names of specific patients, their illnesses and the method of their cure, were read some 1,800 years ago by Pausanias and can still be examined by visitors today in the archaeological site’s museum.

One such inscription reads: “Arata, a Spartan, suffering from dropsy (oedema, the retention of water in the body). On her behalf, her mother slept in the sanctuary while she stayed in Sparta. It seemed to her that the god cut off her daughter’s head and hung her body with the neck downwards. After a considerable amount of water had flowed out, he released the body and put the head back on her neck. After she saw this dream, she returned to Sparta and found that her daughter had recovered and had seen the same dream.” In more recent times, Jungian scholars have suggested the dream healing therapy practiced at Epidaurus and elsewhere represents the early forerunner of modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

KOS

Concerning Kos and other major Asclepieia, it was not accidental that they were located in the open countryside, among beautiful, clean surroundings, where the climate was healthy and the water pure. Indeed, these sanctuaries provided a holistic, innovative approach to health and the prerequisites for physical, psychological, social and spiritual well-being.

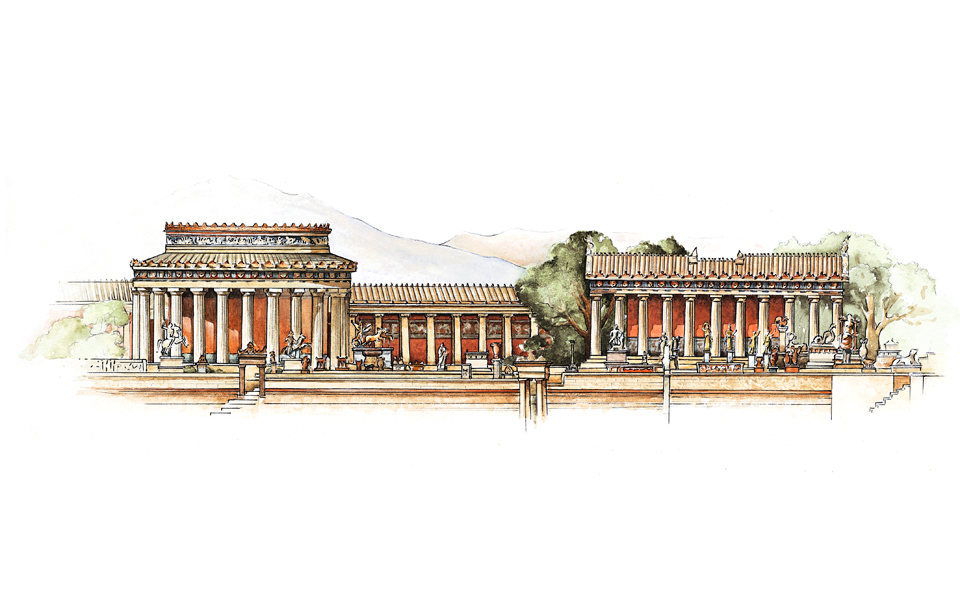

During its heyday in Hellenistic and Roman times, Kos’ elaborate Asclepieion must have been a stunning sight, set 100m above sea level on the eastern slopes of Mt. Dikeos, about 4km outside the town of Kos. Rising in three artificial terraces above the ground, the sanctuary was adorned with monumental gateways and staircases; U-shaped stoas (colonnaded, roofed walkways/shelters); Doric, Ionic and Corinthian temples; altars; fountains; statues displayed in wall niches; and eventually a large Roman bath complex (3rd c. AD).

Kos was a headquarters for the close-knit priestly order of the Asklepiadai, supposed descendants of Asclepius, who guarded their secrets of medicine and advocated the treatment of patients not through dreams, but in accordance with the teachings of Hippocrates.

ATHENS

On the South Slope of the Athenian Acropolis, a small Asclepieion was established in 420/419 BC, during the Peloponnesian War, when Athens’ inhabitants were largely penned inside their defensive city walls and disease was rampant. Plague had broken out in 430 BC and claimed as one of its first victims Pericles, the city’s great leader. To stem the rising tide of illness, a private citizen, Telemachos of Archanes, took the initiative of having a sacred serpent representing Asclepius brought across the Saronic Gulf by boat to Piraeus, then up to the Acropolis. A diminutive sanctuary was established that included the main components of the mother site at Epidaurus: a sacred spring, altar, temple dedicated to Asclepius and Hygieia, two-storied Doric stoa/abaton, ceremonial dining room and a monumental gateway (propylon).

Pausanias (1.21.4) writes that the Athenian Asclepieion “is worth seeing both for its paintings and for the statues of the god and his children.” He also describes an unusual votive offering displayed in the sanctuary: a military/hunting breastplate produced by Sauromatae craftsmen (from western Scythia, north of the Black and Caspian Seas), consisting of a linen garment covered with snake-like scales made from horses’ hooves. Marble “Kouros” statues were also brought to Asclepieia as dedications to the healing god, a large example of which, from the sanctuary in Paros, is now in the Louvre Museum. In the 1st c. AD, the Roman emperor Domitian sent locks of his hair, a mirror and a jeweled box as votive gifts to Asclepius at Pergamum.

The practice of transferring the power and cult of Asclepius through the conveyance of sacred serpents was not unique to Athens, but also reported at sites including Sikyon, where, according to Pausanias (2.20.2), “the god was carried to them from Epidauros on a carriage drawn by two mules…in the likeness of a serpent.”

The establishment of the Asclepieion at Rome was also triggered by an onset of plague (293 BC), although the cult of Asclepius/Aesculapius had previously begun spreading into the Italian peninsula during the 5th c. BC. In the face of rising illness in the city, a delegation was dispatched to bring a serpent from Epidaurus – which, upon its arrival at Rome, legend holds, slithered off the ship and swam onto the small island in the midst of the Tiber river. There, the Romans founded an Asclepieion safely removed from the crowded city. Later, the island’s Travertine seawalls were configured to resemble the bow and stern of a Roman ship – a tribute to the original vessel that had arrived from Epidaurus. Today, the water-worn traces of a relief carved on the island’s downstream “bow” still depict Aesculapius’ snake-entwined staff.

“Hundreds of large and small Asclepieia were established in ancient Greek and Roman times, with almost every big town seeking to provide what was essentially a health-care facility for its residents and neighbors.”