If we wanted to trace Georgios Papanikolaou’s life on a map, we’d start our line at his birthplace, Kymi in Evia, and then run it through Athens, the German cities of Jena, Freiburg and Munich, and then down to sunny Monaco. It would briefly pause during the Balkan Wars, in which Papanikolaou fought, only to move on to New York before finally stopping in Miami. This geographical exercise would prove that for Papanikolaou the researcher, the world had no borders.

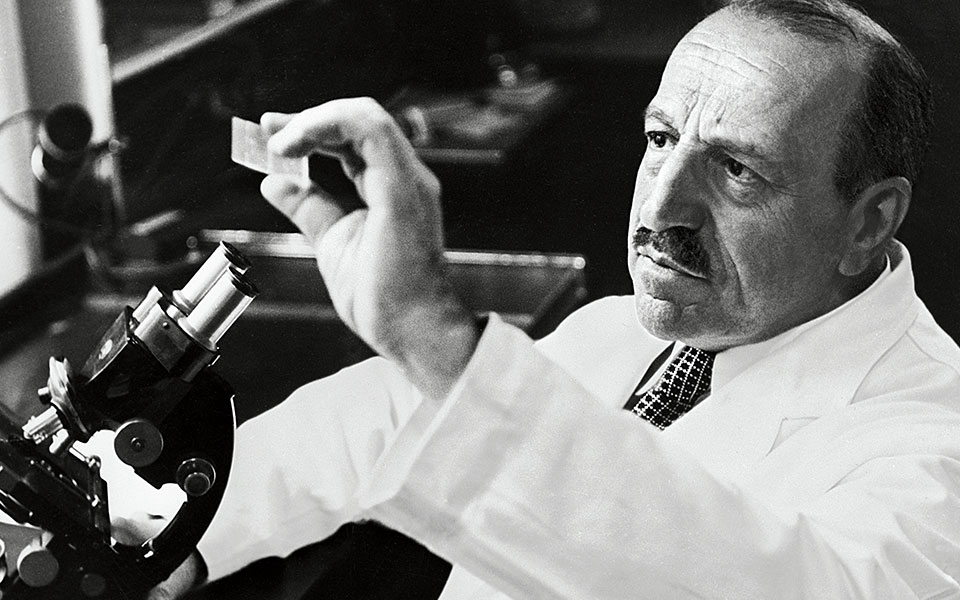

Millions of women are grateful to him for the test he discovered and presented for the first time in 1928. He was 45 years old at the time, and the medical community was initially skeptical about him and his work. Nearly a century has now passed, and there is still no sign of a better, more modern method for the prevention of cervical cancer. And yet, Georgios Papanikolaou almost didn’t become a doctor.

He was born May 13, 1883, the second son and third child of Nikolaos Papanikolaou a doctor popular enough to be elected mayor and subsequently a Member of Parliament. According to the tradition of those times, the firstborn son had to follow his father’s career. But as his older brother chose law, Georgios, who was already showing a particular inclination towards medicine, took up the responsibility instead.

After primary school, Georgios left for Athens where he started learning French, a language considered a necessary skill for young Greek gentlemen. Leaning towards music, he also studied violin for eight years at the Lautner School of Music. In 1898, aged only 15, he managed to get into the School of Medicine of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. During his university years, he formed strong friendships with other students, including Dimitris Glinos and Alexandros Delmouzos from the School of Philosophy. They were dedicated to the demotic movement, an attempt to make the demotic, colloquial Greek the predominant language in place of the cultivated imitation of Ancient Greek known as katharevousa. In these matters and others, Glinos and Delmouzos influenced Papanikolaou.

To this day, the Pap Test is used worldwide for the diagnosis of cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases of the female reproductive system.

philosophical thought

Having finished school, Papanikolaou returned to Kymi under the influence of the new ideological movements and philosophical theories of the early 20th century and withdrew to his birthplace to cultivate the land, study philosophy and biology, and occupy himself with language and demoticism. He was influenced by the theories of Kant, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Goethe, and by Ernst Haeckel’s book “The Riddle of the Universe.” Nevertheless, scientific research still fascinated him.

Knowing this, his father sent Georgios to Germany for further studies in 1907. For three years, he studied Biology and Zoology, first in Jena, then Freiburg and finally Munich, where he acquired his PhD. This “German period” of his life was full of explorations and discoveries, and it was during this time that Papanikolaou decided that research and biology would be the twin purposes of his life. He wrote to his father: “I am no longer a dreamer. Science snatched me out of Nietzsche’s hands. I’ve got my feet on the ground.”

Scientific Odyssey

When he returned to Greece in 1910, Papanikolaou realized that the conditions were not favorable to his plans for the future. He married the educated and open-minded Andromachi – or Machi, as he called her – Mavrogenous (a descendant of the Mavrogenous family who made history fighting against the Ottomans in the Greek War Of Independence). Right after their marriage, he decided to leave Greece again. He clarified his position to his parents, explaining that his “ideal in life was neither to become rich, nor to live happily, but to work, act, create and do something worthy of a man who is moral and strong.”

The young married man’s first stop was at the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco. In 1911, he took part in a scientific expedition on Prince Albert’s oceanographic vessel L’Hirodelle. A year later, during the Balkan Wars (1912-1913), he was conscripted into the army as an Assistant Medical Reserve and returned to Greece. During this time, he met a number of compatriots who had previously migrated to America and were now back in Greece voluntarily, to fight. From conversations with them, he began to form the opinion that the New World was the place where the conditions for scientific research were at their best.

On October 19, 1913, Georgios Papanikolaou, together with his wife, disembarked in New York. The couple initially faced serious financial difficulties. At the beginning, they lived in a single room on 116th Street and both worked at Gimbels Department Store. He sold carpets and, in the evenings, played the violin in various restaurants, while she sewed buttons for five dollars a week.

However, although poor and seemingly unknown, Papanikolaou overcame the difficulties quickly. He found work as a journalist for the Greek paper Atlantis and was later recruited by the New York Hospital, having been recommended by Professor Thomas Hunt Morgan of Columbia University. Dr Morgan knew Papanikolaou from Germany and appreciated his work. Finally, in October 1914, he started working at Cornell University where he would remain for the next 47 years. Two months later, his wife Machi joined him as his technician.

Papanikolaou’s bibliography consists of 158 articles and five scientific books. The most prominent of them is the famous Atlas of Exfoliative Cytology. The book is a milestone not only in the science of cytology, but also in the medical bibliography of the 20th century as a whole.

Even though he never received a Nobel Prize (although he was nominated twice), he was awarded many medical prizes, both during his life and posthumously.

the Pap test

The 1920s were the most productive but also the most difficult years of his efforts. The experimental stage of his research began with vaginal smears from actual guinea pigs. The results were encouraging. Shortly afterwards, Papanikolaou began to experiment on vaginal smears from his own wife and, eventually, female patients at a hospital affiliated with Cornell.

When he identified cancerous cells in a sample from a woman with cervical cancer, he confessed that it was one of the most staggering experiences of his scientific career. The first clinical trials proved the diagnostic value of cytological examination of smears. This work became the cornerstone that established his method for the timely diagnosis of cervical cancer. In 1928, he made his first announcement titled “New Diagnosis of Cancer.” It was first received with doubt by the American medical community. He, however, was absolutely confident about its value and continued his research with greater zeal.

Thanks to his perseverance, Dr Pap’s pioneering cytodiagnostic method became both accepted and internationally known under the medical abbreviation Pap test. To this day, it is used worldwide for the diagnosis of cervical cancer, precancerous dysplasia and other cytological diseases of the female reproductive system.

The epilogUE in Miami

Papanikolaou worked relentlessly for almost half a century at Cornell. He didn’t take any vacations, apart from one short scientific trip to Europe where he slipped in his hometown Kymi as the final stop. In 1961, despite the fact that he was 78 years old, he decided to leave New York and settle in Miami. He planned to undertake the organization and management of the Miami Cancer Institute. However, he did not have the chance to inaugurate the institute himself; he died suddenly of a heart attack on February 19, 1962. The Institute was renamed the Papanicolaou Cancer Research Institute.

Throughout his career, the great researcher and scientist kept unbreakable bonds with Greece and maintained his interest in Greek politics and the various intellectual and social movements in the country. His wife continued his work in Miami until her death in 1982. She believed that one is born a scientist and that research comes to fruition only inside labs. For this reason, she said, “There was no other option for me but to follow him inside the lab, making his way of life mine.” She was so devoted to him that she decided not to have children in order to always be by him. She said that she never regretted it.