By Dimitra Manifava

For decades right up to the late 1980s, feta cheese, olive oil and small quantities of retsina wine were Greece’s only important food exports. Many consumers abroad, in fact, had been using Greek olive oil during this time without knowing it, since around 60 percent of the country’s olive oil yield was sent to Italy, where it was packaged and sold as an Italian product.

In those years, the Greek food industry, which had experienced a boom in the late 19th century, could do little more than cover domestic demand. Its biggest export markets, such as they were, happened to be countries with sizeable Greek immigrant communities, including Germany, Belgium, the USA, Canada and, to a lesser extent, Australia and Sweden.

© George Tsafos

© Shutterstock

© Katerina kampiti

The situation today, thankfully, is very different: some of the world’s greatest chefs use avgotaracho (salt-cured fish roe) produced by Trikalinos in Messolongi; the Kozani-based company Alfa exports its traditional savory pies all the way to Washington, D.C.; global dairy firms are battling one another for shares in the Greek yogurt market, popularized by Fage; Greek fish farms are the world’s second leading source for farmed sea bream and sea bass; Dodoni feta has cornered 90 percent of the Australian market for the cheese and 30 percent in the USA; and the oil and olives of Olympia Xenia can be found in supermarkets around the world.

The Beginnings

The Greek food industry has deep roots: the country’s first large-scale flour and olive oil mills opened in 1855 and Pavlidis established a major chocolate factory in Athens in 1876. Commercial food manufacturing dates to 1870, with the opening of the Triantis flour mill and the Karambelas pasta factory in the western port town of Patra.

More large industrial units followed in the early 20th century, including the Benvenice rice plant in Thessaloniki; Natzari & Co, the noted rice processing factory (it opened in 1905); the Greek Canning Company, one of the oldest in Europe (it began operating in Nafplio in 1915 and is still active under the brand name Kyknos); and Loulis Mills in Volos in 1917.

Mass migration into Greece after the catastrophic 1919-1922 Asia Minor military campaign, along with rapid urbanization, gave a significant boost to the Greek food industry, as refugee Greeks from Turkey infused it with capital and know-how.

© Designed by Thanos Kakolyris

The Papadopoulos brand is a good example; a family of biscuit makers from Istanbul landed in Piraeus and found a country that knew nothing about biscuits. The now-famous company began life as a bakery before opening its first factory in 1938.

In 1917, Greece had 1,244 food processing facilities, with an additional 221 opening from 1921 to 1926. The main centers of production were Athens, Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Patra and Volos.

Bust

The German occupation of Greece in World War II halted the growth of the domestic food industry, and the anticipated post-war rebound proved elusive. A further population shift to the cities resulted in a steep decline in agriculture and food production, while most investments were directed towards the real estate and services markets rather than manufacturing.

However, as Greeks saw their standard of living shoot up in the mid-1980s, the food sector became particularly lucrative, attracting a fresh wave of investment, both of domestic and foreign capital. Several Greek brands were taken over by foreign companies. The Ivi-Panagopoulos soft drinks firm, for example, was acquired by PepsiCo in 1989; the chocolate maker Pavlidis was bought by Kraft and, more recently, by Mondelez; and the coffee company Loumidis was acquired by Nestle in 1987.

Restart

The collapse of communism in the Balkans led to the gradual liberalization of those countries’ economies and increased foreign trade in the region, providing a major boost to the Greek food industry by creating new markets for its products, as well as giving the country a key role in regional development.

In fact, exports to these markets – which grew steadily as living standards improved in the former communist countries – and investments by Greek producers (including the dairy company Olympus and the snack-maker Chipita, among others) have been important sources of revenue in the sector since the start of the current crisis, which saw sales take a serious hit in the domestic market: Central and Eastern Europe account for 68 percent of Chipita’s current annual turnover of €432m, while Olympus has benefited significantly from its activities in Romania, where it first established a presence in the 1990s.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

Crisis Cure

How is the Greek food industry faring today? Shrinking demand and turbulence from bankruptcies, takeovers and mergers have certainly done some damage, but on the other hand, the industry is more technologically advanced and export-oriented than ever before, thanks to a realization that the future depends on two, seemingly opposing, pillars of growth: innovation and investment in high-quality, local products.

Synergies with the tourism sector have been instrumental in reshaping the food industry, as the leaps made in the mass catering sector in the past few years have popularized Greek products among foreign visitors and helped their reputations travel abroad.

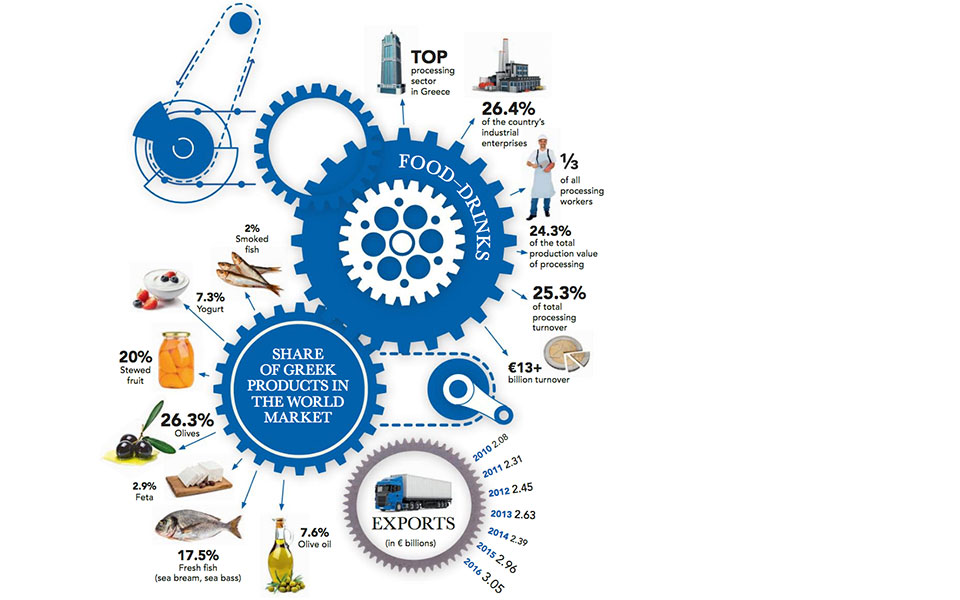

According to a recent report by the Foundation for Economic & Industrial Research (IOBE), carried out on behalf of the Association of Greek Food Industries, food is now the largest sector in Greek manufacturing. Over a quarter of all manufacturing businesses are involved in food and/or beverages (as opposed to an EU average of 12.5 percent), accounting for approximately a quarter of the industrial turnover in the country and likewise producing one quarter of the nation’s gross manufacturing value. The food industry is also the second largest employer in Greek industry, with food and beverage producers providing jobs to one-third of the manufacturing workforce (compared to an average of 13.6 percent across the EU).

The sector saw its revenues increase by an average annual rate of 1.86 percent from 2009 to 2016, despite the economic crisis, thanks to the rise in exports and particularly, albeit at a slower pace, the rise in added-value exports.

From €2.1 billion in 2010, Greek exports of food products shot up to more than €3 billion in 2016, with the trend continuing. Some products, in fact, including olives, fresh fish, olive oil, and processed food goods like fruit preserves and yogurts, are taking over large chunks of the global market.

© Shutterstock

© Shutterstock

Experts argue that the Greek food industry could be even more powerful with further consolidation. Ninety percent of the businesses in the sector are classified as very small, employing a staff of less than 10 people, while only 1 percent are medium-sized businesses, with a workforce of 50 to 249 people.

In 2016, Greece had just 24 big enterprises with 250 or more workers; these accounted for 32 percent of the industry’s annual turnover. Nevertheless, it’s a dynamic sector capable of attracting domestic and foreign investor interest. A recent study by PricewaterhouseCoopers identified 110 food companies in the Greek market that would make promising acquisitions, as well as 20 firms that could play the role of consolidator.

Greek food export figures could rise if more products receive protected designation of origin (PDO) and geographical indication (PGI) status. Such products offer significant added value, offsetting the fact that the country does not have – and may never have – a “heavy” food industry.

The EU’s register of certified food products includes 76 PDOs and 30 PGIs in Greece, while six more are awaiting approval. Furthermore, 116 Greek wines have been granted PGI status and 33 have PDO status, while 16 other alcoholic beverages enjoy PGI status as well.

There’s an important clue to Greek success in these PDO numbers; in the end, the Greek food industry will rise to overcome any challenges it faces because it is based on outstanding products and remarkable raw materials.