Thanks to the musicologist Melpo Merlie and her collection, an aural trace, undefeated by the ravages of time, will always remain of Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936). Generation after generation will be able to hear his voice singing “Digenis” and “Death,” including the stirring lines from the latter: “Late last night, I passed by Death’s house and heard his wife nagging, ‘Haven’t I told you, Death, time and time again? Where there are five take three, where there are three, take one, but where there are two, don’t take anyone at all.’”

It wouldn’t be fair to talk about Venizelos, arguably the most influential Greek politician of the 20th century, without mentioning his extraordinary (and revealing) involvement with Greek folk songs and with the people who continued to create work in this genre. In addition to his own enjoyment of folk music, both as a listener and a singer, Venizelos also figured in its more contemporary songs: a hero, praised above all in Cretan songs – but also a negative figure, decried in dirges from Mani, where mothers steeped in grief at the loss of their sons at the front censured him with the candor of incurable sorrow. That split in how the folk song tradition treats Venizelos reflects the fact that he is a historical figure. In other words, it separates him from the space of ideal or idealized heroes, of legends which admit no criticism, and depicts him instead as a historical subject, and therefore something that can be controlled.

© Niki Stavrou/Kazantzakis Editions

In the case of Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957), too, it would be inconceivable, in the attempt to compose even the most cursory biography, to overlook or underestimate his exceptional relationship with folk song: Kazantzakis apprenticed himself to the genre and drank insatiably from its wellspring, just as he fed insatiably from every spiritual or intellectual realm he encountered. His first substantial contribution to letters, the tragedy “The Master Builder” (1910) was a retelling of the famous folk song “The Bridge of Arta.” His volume “Tercets” and his “Odyssey: A Modern Sequel” (which he insisted on spelling with only one “s” in Greek), which is to say the entirety of his poetic production, is diversified and enriched with words borrowed from rhyming folk compositions (Cretan compositions above all) but also with his own creations (usually quite complex), which he shaped in the manner of those anonymous lyrics. In the 33,333 15-syllable lines of the Odyssey – one of the longest poems in the world – Kazantzakis, in order to narrate the adventures of his wily and perpetually spiritually thirsty hero (an obvious alter ego of the poet) after his return to Ithaka, pursues with unbridled enthusiasm elements from the folk tradition in general, and more specifically from the oral tradition, from wherever Greek was spoken, in all its many varieties. Kazantzakis worked in a way akin to a writer of funerary epigrams who wishes to immortalize voices and “tongues.”

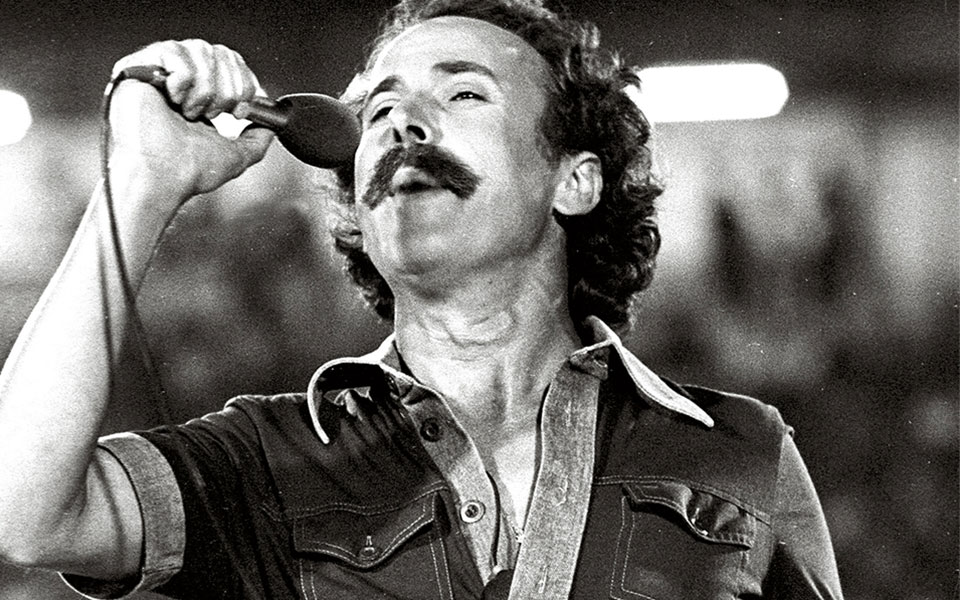

Finally, with Nikos Xylouris (1936-1980), things are simple. They are, in fact, as simple as an unambiguous mathematical equation: Nikos (or Psaronikos, as he was known) = folk songs, and Cretan folk songs in particular. His interpretations of songs in the folk canon are unparalleled. With the chords of his soul, he gave new meaning to a song that probably had a bucolic origin, a hunting song called “When Will the Stars Shine Bright,” and, in the underground nightclubs of Plaka during the years of the dictatorship, transformed it into a war song, something like a hymn to the passion for freedom.

© Eleftherios K. Venizelos Museums, Athens

Is there truly something we might call a “Cretan glance”? Is there a way of conceptualizing and experiencing the things of this earth – in all their aspects, from everyday life to celebrations, weddings or other occasions – which might be claimed to be exclusively Cretan, in addition to being entirely virtuous and good, almost metaphysical? Is there a way of expressing what Dionysios Solomos called the “movements of the soul” – unyielding obstinacy, generous hospitality and pride, which, in the shallowest of characters is transformed into self-adoration – which could also be characterized as exclusively Cretan?

Let’s leave genetics out of it, in part because we’re in danger of slipping into hyperbole and, in the end, insulting the entire island and its unique, long-lived intellectual tradition. And yet Kazantzakis, sure of the unique identity of his birthplace, introduced both the term and the hypothesis concerning a “Cretan glance,” a philosophical way of seeing that looks on chaos or on danger without fear or delusions. References to the “Cretan glance” can be found throughout his extensive and varied writings, while a brief synopsis of the theory can be found in his “Report to Greco, where he writes: “My personal life has some value, extremely relative, for myself and no one else. The sole value I acknowledge in it was its effort to mount from one step to the next and reach the highest point to which its strength and doggedness could bring it: the summit I arbitrarily named the ‘Cretan Glance.’” For Kazantzakis, man sprouts wings and flies only if he reaches the edge of the yawning chasm.

© Dimis Argyropoulos

Venizelos, Kazantzakis and Xylouris were three figures of rare quality, each exceptional in his own realms − since none of this triad was one-dimensional. And while the writer-philosopher in the group may have believed that Crete is shaped primarily by its kouzoulous, its screwballs, rather than its family men, none of those three were screwballs in the least.

The politician in this group, leader of the Cretan Revolution that began in the village of Theriso and the prime minister of the entire country on seven separate occasions, saw Greece from the vantage point of Crete. He saw a greater Greece – geographically, politically, and spiritually – than the one defined by its borders at the end of the 19th and the first quarter of the 20th centuries, and left extraordinarily important marks on the nation’s body, expansive and bloody marks that continue to invite the work of researchers.

Kazantzakis, meanwhile, saw the whole world from Crete. At the same time, during his travels all over the globe, he kept glancing back towards Crete, or perhaps towards the image of Crete he himself had formed. Now, at the end of the second decade of the 21st century, he remains the Greek author with the widest international recognition – even more so than CP Cavafy – and his works, including the difficult “Odyssey: A Modern Sequel,” continue to be translated. (For many Cretans, however, their island appears more authentically, less a thing of myth, in the pages of Ioannis Kondylakis.)

Xylouris’ glance embraced Athens, and from there all of Greece, all while still keeping his Cretan heritage intact. His greatest accomplishment was that his songs transcended the local folk elements within them to become a part of the national cultural heritage of all Greeks. They belong to us all.