ZEUS OR POSEIDON ca. 460 BC

The bronze “Zeus or Poseidon,” a shipwreck survivor and one of the most well-known ancient Greek statues today, was discovered in the Trikiri Channel, off the north coast of Evia, in 1926. At first, only one arm was recovered. Two years later, however, acting on the report of a concerned citizen, the mayor of the village of Istiea, Antonios Skouropoulos, gathered a group of officials, requisitioned a boat, staked out a suspicious-looking fishing trawler anchored near the findspot, and caught a crew of antiquities thieves red-handed as they attempted to wrest the remainder of the statue from the seabed. The would-be thieves were arrested, but not before they broke off the statue’s other arm in their efforts. Officials attempted the statue’s salvage, but were delayed for two days by stormy seas. Finally, on September 26, 1928, they managed to tow the shell-encrusted “Artemision Bronze” to shore. Today, fully cleaned and restored, the 2.09m-tall figure towers majestically above the National Archaeological Museum’s visitors, seemingly aloof to the differing opinions swirling below him concerning his identity and his creator.

He is most likely Zeus, with near-perfect anatomy and a serene composure, preparing to release a hefty thunderbolt, rather than a slim trident – given the now-missing weapon’s large-diameter shaft indicated by his curled, gripping fingers. Fifth-c. BC sculptors who may have created the statue include Kalamis, Onatas, Myron, Kritios and Nesiotes. Further investigation of the Artemision Wreck site in 1928-29 revealed the famous Horse and Jockey statue group as well, along with a lead anchor, bronze nails, a piece of wood, and pottery including Pergamene skyphoi (wine cups). Judging from this, and noting testimony from Pausanias, archaeologist Seán Hemingway concludes the ship was bound for Pergamon, carrying booty from the Roman sack of Corinth in 146 BC.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

MERENDA KOUROS 540-530 BC & PHRASIKLEIA KORE 550-540 BC

Together forever: in 1972, a kore (“maiden”) and a kouros (“naked youth”) were discovered buried side by side in a pit, in an ancient necropolis at Merenda in southeastern Attica. Their story is one of family tragedy, foreign invasion and inspired archaeological detective work. Laid to rest in the late 6th or early 5th c. BC, the pair were long forgotten. In 1730, however, Michel Fourmont, a French Catholic priest and antiquarian, noted an inscribed stone that had been reused as a column capital in Merenda’s Church of the Panaghia. In fact, it was an ancient statue base, which referred to “Phrasikleia,” a young woman who had died before having the chance to wed.

Removed to Athens in 1968, the stone remained in obscurity until the Merenda statues were later unearthed near the chapel. Archaeologist Efthymios Mastrokostas recalled the inscribed base and deduced the kore – holding a lotus bud, symbolic of life and death (the scholar Mary Stieber describes it as a flower “plucked before it could bloom”) – might be the virgin Phrasikleia. Confirming his conclusion was a large lead ring found in the grave, which had originally affixed the kore to her pedestal. It fit the base perfectly.

Who were the deceased? The statue of Phrasikleia, an ornate masterpiece by Aristion of Paros, and the kouros (from a later date), perhaps representing her brother, were thought to commemorate members of the Alcmaeonid clan, political opponents of the Peisistratids, who were exiled and may have buried their family grave markers following an incident of vandalism, or to protect them from one. The kouros, snapped off above the ankles, was later meticulously buried with his broken arms. A 2015 study of four associated black-figure lekythoi, however, has shown that the interment dates no earlier than 480-460 BC. The statues, probably damaged by marauding Persians, were treated as proxies, painstakingly buried in loving memory of unfulfilled youth.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

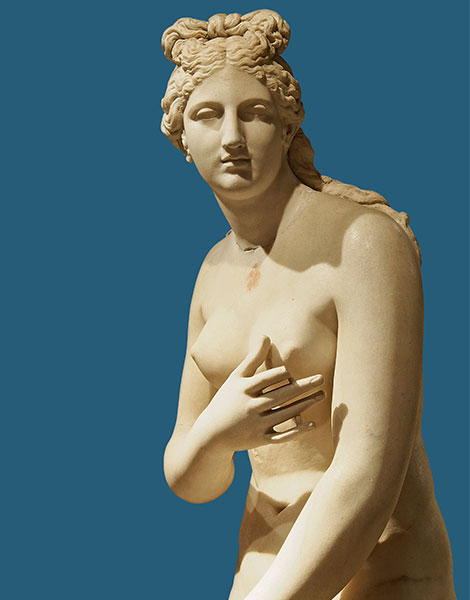

APHRODITE OF SYRACUSE 2nd c. AD

The Aphrodite (Venus) of Syracuse, discovered at Baiae in the Bay of Naples (once a hedonistic seaside playground for ancient Rome’s rich and famous), probably adorned a luxurious bath or garden. Behind this beguiling goddess’ curves and polished surfaces lies an important legacy of artistic revolution. Around 350 BC, the Athenian sculptor Praxiteles pioneered a new perception of nudity in Greek art when he created the first beautifully unclad female figure, the Aphrodite of Knidos – which Pliny the Elder described as “superior to all the statues … of any … artist that ever existed.”

So popular was this statue that many marble or bronze copies – and copies of copies – began to appear. The original sculpture, now lost, depicted Aphrodite standing naked, modestly covering her genitalia with her right hand, while her breasts were left fully exposed. In the 3rd or 2nd c. BC, however, an innovative copyist in Asia Minor showed the goddess shielding one breast in addition to her pudendum.

This new type, known as Venus Pudica (Modest Venus), led to further copies – especially the Capitoline Venus (2nd c. AD) which subsequently inspired the unknown sculptor of the Aphrodite of Syracuse. Appearing more than three centuries after the earliest nude males, Praxiteles’ Knidian Aphrodite was a bold departure. Previously, women’s natural beauty had only been hinted at. Pheidias’ Parthenon sculptures (440s/430s BC) epitomize the High Classical taste for diaphanous, clinging (“wet”) drapery that accentuated the female anatomy. Aphrodite reclines languidly on the east pediment, her chiton slipping off one shoulder and thinly concealing her body’s curves. This is the veiled voluptuousness, self-confidence and innately powerful sexiness that Praxiteles finally reveals, and which later Roman sculptors likewise celebrated.

MARATHON BOY 340-330 BC

Nearly 95 years after being lifted from the sea in a fisherman’s nets, the Marathon Boy is still surrounded by mysteries – who created him, what is he holding and how did he end up where he was found? With graceful, perfectly proportioned anatomy, an exaggeratedly S-curved body and a distinctive positioning of the head, he seems to come from the Praxitelean school, perhaps from the hand of the master himself. But who is this small boy (130cm), with delicate features, undeveloped muscles and a thoughtful gaze? He has variously been identified as an athlete; a contest-winner (indicated by his headband); the god Hermes; or an older man’s companion.

From the early 5th century BC, painted vases depict mature men accompanied by nude boys, who were their apprentices, servants, musicians and lovers. Plato relates that handsome boys often provided men with comfort and amusement, receiving some wise guidance in return. Or is the Marathon Boy an ephebe (adolescent) or perhaps a “servant statue?” What he’s doing might provide a clue. Is he pulling a ribbon from a container? Preparing to pour from one vessel to another? Picking fruit and putting it in a bowl? Or holding a tray of delicacies, possibly to offer guests in a well-to-do home? His extended hip and raised foot result in an unbalanced center of gravity, thus requiring him to be supported, conceivably on a column or against a wall.

Italian archaeologist Brunilde Ridgway has long suspected that the “Marathon Boy may have been such a servant statue, perhaps from Herodes Atticus’ [Marathon] villa,” since such adolescent figures were common in Roman houses. Despite recent searches, the statue’s 1925 findspot, near “some tiny island,” has also remained obscure, leaving us to wonder: was the Boy simply jettisoned, or is there still an important shipwreck to be discovered?

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

THE ANAVYSSOS KOUROS ca. 530 BC

The serene expression of the Anavyssos Kouros, with its silent, powerful bearing, gives little hint of the Archaic statue’s dark past of theft, dismemberment and clandestine exportation. The statue, identified as “Kroisos” from an inscription on its base, was “kidnapped” after its discovery and borne away on a ship in the dead of night. In the early 20th c., antiquity smuggling became a profitable activity in the Greek countryside.

One such area was the Attic village of Keratea. It was here that this statue was unearthed in 1936, deliberately broken into ten pieces and surreptitiously shipped out from the coast of Anavyssos, bound ultimately for France. Thankfully, the Greek police recovered the statue from a Parisian antiquities dealer the following year, according to an account by the National Archaeological Museum’s then director Alexandros Philadelpheus. While investigating the Anavyssos district in 1911, Philadelpheus had heard from locals about “ancient marble remains on a certain hill… and that statues had been smuggled from there.” Apparently, this was the spot where “our Kouros was discovered… and smuggled abroad.” The statue arrived back in Athens in 1937 – in three packing crates – but without a base.

Additional reports in 1938 and 1949 describe two villagers from Keratea wishing to sell a block inscribed with an epigram honoring a young aristocrat, possibly of the Alcmaeonid clan, who died in battle: “Stop and show pity beside the marker of Kroisos, dead, whom, when he was in the front ranks, raging Ares destroyed.” Although now installed beneath the Anavyssos Kouros, the base may not be correct, since some accounts of its discovery place it nearer to the findspot of two other Archaic statues, one now in New York.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

HEAD OF A WARRIOR FROM AEGINA ca. 490 BC

In April 1811, a small group of friends – aspiring young architects, painters and archaeologists on a Grand Tour of Ottoman-ruled Greece – sailed from Piraeus, wishing to explore the ruins of the temple of “Jupiter” in Aegina. Little did they know they were about to make an extraordinary discovery.

Camping in tents within the hilltop sanctuary now understood as belonging to the Aeginitan goddess Aphaia, they set to work excavating and recording the building’s fallen architectural members. On the second day, their leader Charles Cockerell notes, one of their workers “struck on a piece of Parian marble, which … turned out to be … the head of a helmeted warrior, perfect in every feature. It lay with the face turned upward.” Excited, they expanded their search and ultimately found “no less than sixteen statues, thirteen heads, legs, arms, etc., all in the highest preservation,” which once had decorated the temple’s pediments.

Working quickly, Cockerell, along with John Foster, Jakob Linckh and Carl Haller von Hallerstein, packed up the group’s precious finds and quietly shipped them after dark back to Athens – eventually to be displayed as masterpieces of Late Archaic/Early Classical Greek art (ca. 500-490 BC) in Munich’s Glyptothek museum. What they didn’t realize, however, was that below their feet lay many more treasures. A passage in a nearby cave, where Cockerell’s party had unwittingly billeted their workers, led to an adjacent reservoir and underground aqueduct. Here, in 1901, writes archaeologist Adolf Fürtwangler, “another six heads with the fragment of a seventh were … found in the depths of the cistern … and … shaft” – including this Warrior Head. Dating to the same era as the pedimental sculpture, but recovered alongside shattered statue bases, these heads likely belonged to votive dedications that once stood in Aphaia’s sanctuary.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

ANTIKYTHERA YOUTH ca. 340-330 BC

Salvaged from the Antikythera Wreck, one of the most significant ancient shipwrecks ever discovered, the statue known as the Antikythera Youth still lives up to the initial description (1901) given by archaeologist Panagiotis Kavvadias: “This is the most beautiful bronze statue that we possess, and … it gives us, for the first time, an adequate idea of what bronze statuary was in Greece, and in the 4th century BC.”

Standing nearly 2m tall, with a handsome physique and unusually well-preserved inlaid eyes, the Youth’s present appearance belies its less fortunate condition when recovered in 1900 at a depth of more than 50 meters. The cargo of the Antikythera Wreck was first spotted by Ilias Stadiatis, a member of a sponge-diving crew from the island of Symi who had sought refuge from strong winds near Antikythera. Apparently bored with simply waiting out the storm, the divers decided to explore the ocean floor and lowered Stadiatis, in his bulky brass-helmeted diving suit, to a depth to 45m, where a grim sight awaited him: spread out below was what he perceived in the watery gloom to be a heap of rotting corpses of both humans and horses. Later, the Youth was found lying among dozens of other bronze and marble sculptures, its lower body a jumble of fragments.

Today, cleaned and restored, the Antikythera Youth positively seems to glow, with its radiant bronze skin, evocative pose and penetrating stare. This is how the ancients must have seen bronze sculptural masterpieces – the bright material and the outstandingly realistic representations of their subjects doubtless inspired awe in those beholding these works. Variously identified as Apollo, Hermes, Heracles, Perseus, Paris or simply an unknown athlete, the Youth is likely a work of Kleon, a well-known Sicyonian sculptor and Polykleitan successor.

© Dimitris Tsoumplekas

STATUETTE OF A CHILD 1st century BC

This small statuette (63cm) of a boy holding a dog was found in 1922 in the Bouleuterion-Gerontikon (Council House) at the site of the ancient city of Nysa on the Maeander, in western Asia Minor. The figure likely represents a Roman copy of a 3rd-century BC Hellenistic original by an unknown sculptor. The boy’s chubby face, sturdy little legs and hooded cloak, as well as the fact that he is clutching a puppy, imparts a special charm to the artwork.

This modest statuette is an evocative symbol of both the Hellenistic development towards greater naturalism in ancient Greek art and of the turbulent history of early 20th-century Greece. Discovered almost a century ago, in the months prior to the Asia Minor Catastrophe (September 1922), the figure has come to be known as “The Little Refugee” (“Prosfygaki” in Greek). Together with thousands of Greeks and Armenians forced to flee Asia Minor, this ancient object also managed to escape, brought from Smyrna (present-day Izmir) to Greece by the archaeologist Konstantinos Kourouniotis and delivered to the National Archaeological Museum.

The Little Refugee has become a cherished cultural icon, with images of the statuette and stories inspired by its “personal history” used as teaching tools in Greek schools and museums. In antiquity, small statues of children were usually home or garden decorations; or the votive offerings of well-to-do families whose children needed divine protection. Depictions of the young became increasingly common as Hellenistic artists shifted away from classical ideals of physical perfection and began to show more ordinary, naturalistic aspects of people and animals.