“Our house in Salonika was located in a new and very chic neighborhood not far from the sea called Yalilar in the Hamidiye district. It was heavily planted with fragrant vines and trees. Jasmine, Frangipani, Tuberoses, and roses of all varieties filled the neighborhood gardens…. In the spring and well into the late summer, one would get dizzy walking up to the house from the fragrance that hung in the air like a veil.”

– Esin Eden, writing in “Salonika: A Family Cookbook,” co-authored with Nicholas Stavroulakis.

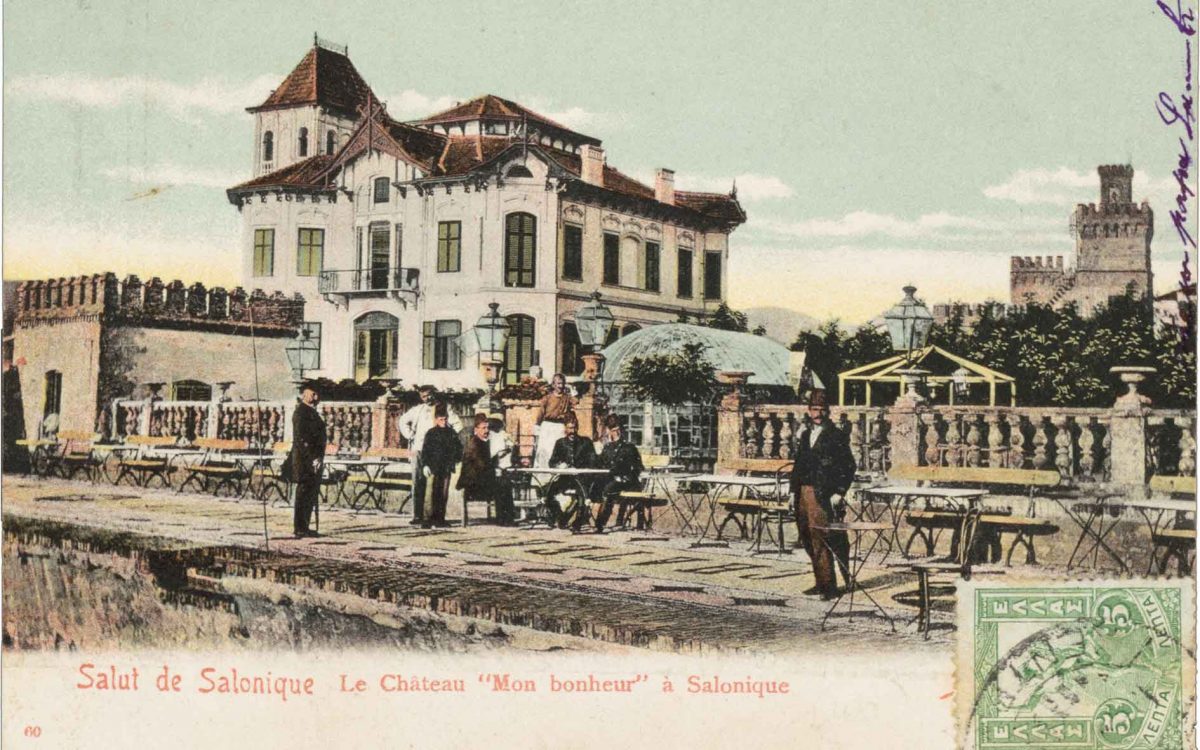

Evocative reminders of the Thessaloniki of her mother’s youth filled the Istanbul childhood of Esin Eden. This paradise of sprawling villas and gardens (“Yalilar” means ‘mansions’) took its name – Hamidiye – from the reigning sultan, Abdul Hamid II, in what were to be the waning days of the Ottoman empire. Called the Exoches in Greek, it stretches eastwards along the shores of the Thermaikos, “exo” (“outside”) of where the old city walls once stood.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

In the Hamidiye, an entirely new type of society flourished. This cosmopolitan upper class was identified primarily neither by faith nor ethnicity, as had been the case for centuries, but rather by their shared refined tastes, level of education, and prosperity. For the first time in the city’s history, Christians, Muslims and Jews lived side by side. They were joined by diplomats, foreign bankers and industrialists, government officials and, later, even by royalty. The sounds of conversation in Greek, Osmanli (Ottoman Turkish), Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) and French filled the gardens and reception halls, and ladies wore the latest European fashions – with the addition of an elegant matching çarşaf and peçe for the Ma’min ladies, like those of the Eden family.

A Wealth of Inspiration

The buildings of Belle Epoque Thessaloniki reflect the city’s unique identity. In contrast to Athens, where neoclassicism served as a stylistic expression of the cohesive identity of the new Greek State, underscoring its cultural and spiritual connection to ancient Greece, Thessaloniki’s eclecticism reflected both the city’s multiculturalism and its European orientation. The style yielded a trove of architectural references and elements – mansard roofs, onion domes, round Art Nouveau windows and the lacy eaves of Swiss chalets – as diverse as the residents’ individual tastes.

There were once over a hundred such buildings here. Some of the finest remain, telling the stories of the residents of the district and of the city itself; along what is today Vasilissis Olgas Avenue, the main artery at the heart of the Exoches, some of the most important events in Thessaloniki’s modern history unfolded.

© ANGELOS PAPAIOANNOU CART POSTAL COLLECTION, E.L.I.A./MIET

The Mosque of the Ma’min

With the mass arrival of Sephardic Jews from the Iberian peninsula, which began in 1492, Thessaloniki’s Jewish community flourished. But in the 17th century, it suffered a sudden reversal. A charismatic mystic named Sabbatai Zevi, claiming to be the messiah, gained an ardent following, especially in Thessaloniki. When the sultan compelled him to convert to Islam, some 300 Sephardic families followed his example. They called themselves the Ma’min, or “the faithful,” although throughout the empire they were also called the Dönmeh, or “the turned.”

The affluent and sophisticated Ma’min community included some of the city’s leading citizens; among these were industrialists from the Kapandji family, the educator Semsi Efendi (Kemal Attaturk’s teacher), and the city’s last Ottoman mayor, Osman Said Bey.

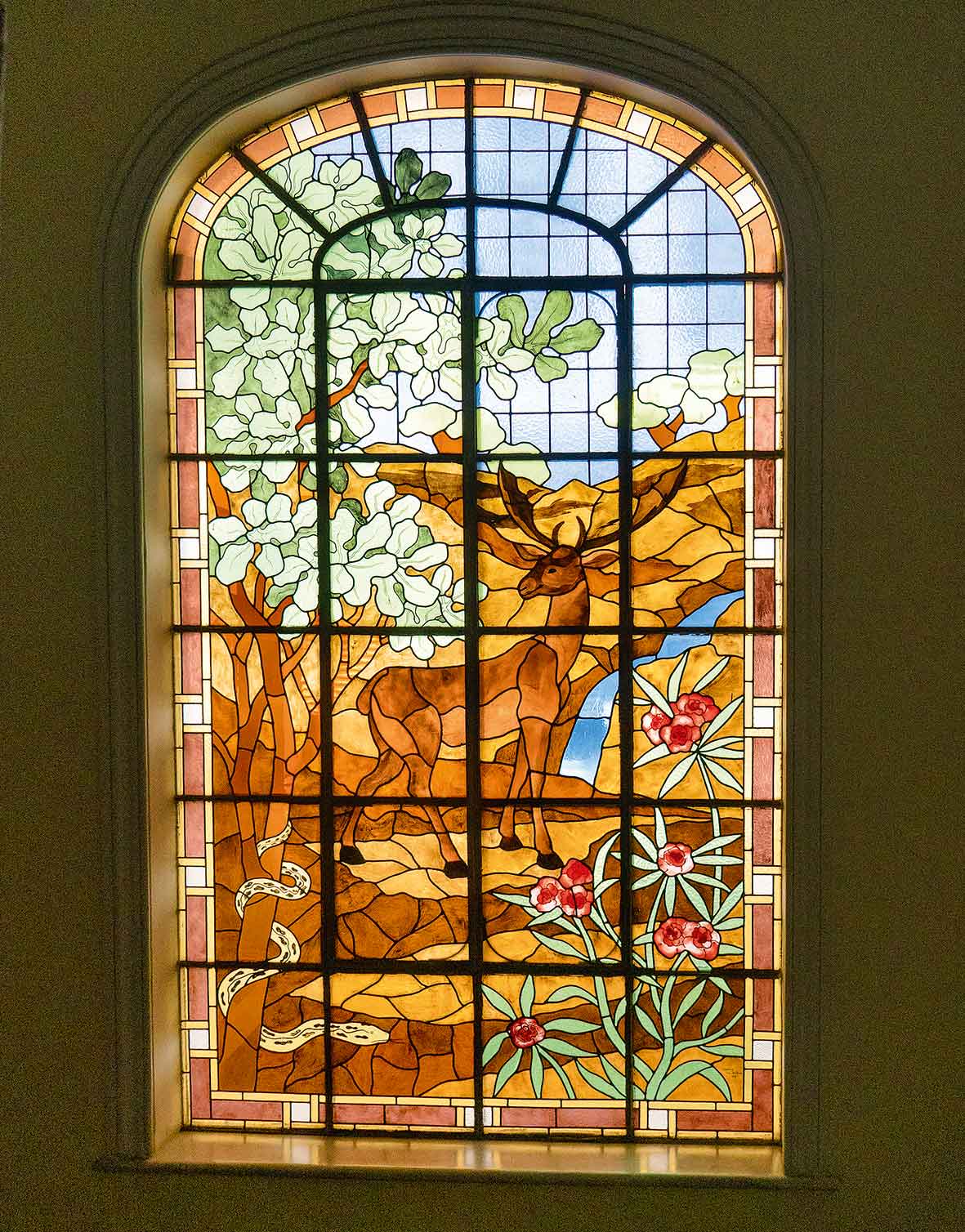

A certain mystery surrounded the community; they married only other Ma’min, and the details of their religious practices were known only unto themselves. The city’s Geni Tzami (“New Mosque”) can be viewed as an architectural expression of the complexity of their identity, uniting a variety of styles, elements, and symbols, including Corinthian columns, Moorish arches, Islamic decorative motifs and an abundance of stars of David.

Info

Geni Tzami: 30 Archeologikou Mouseiou

© Perikles Merakos

The Last Sultan

In early 20th-century Thessaloniki, a movement began that would eventually take down the Ottoman Empire. The Young Turks – the “Salonicans” – eventually gained power in Istanbul, the empire’s capital. In April of 1909, Sultan Abdul Hamid II was deposed and replaced by his brother, a figurehead. Centuries of absolute power for the House of Osman were at an end, and the former sultan was conveyed to the city where the revolution which overthrew him had been born.

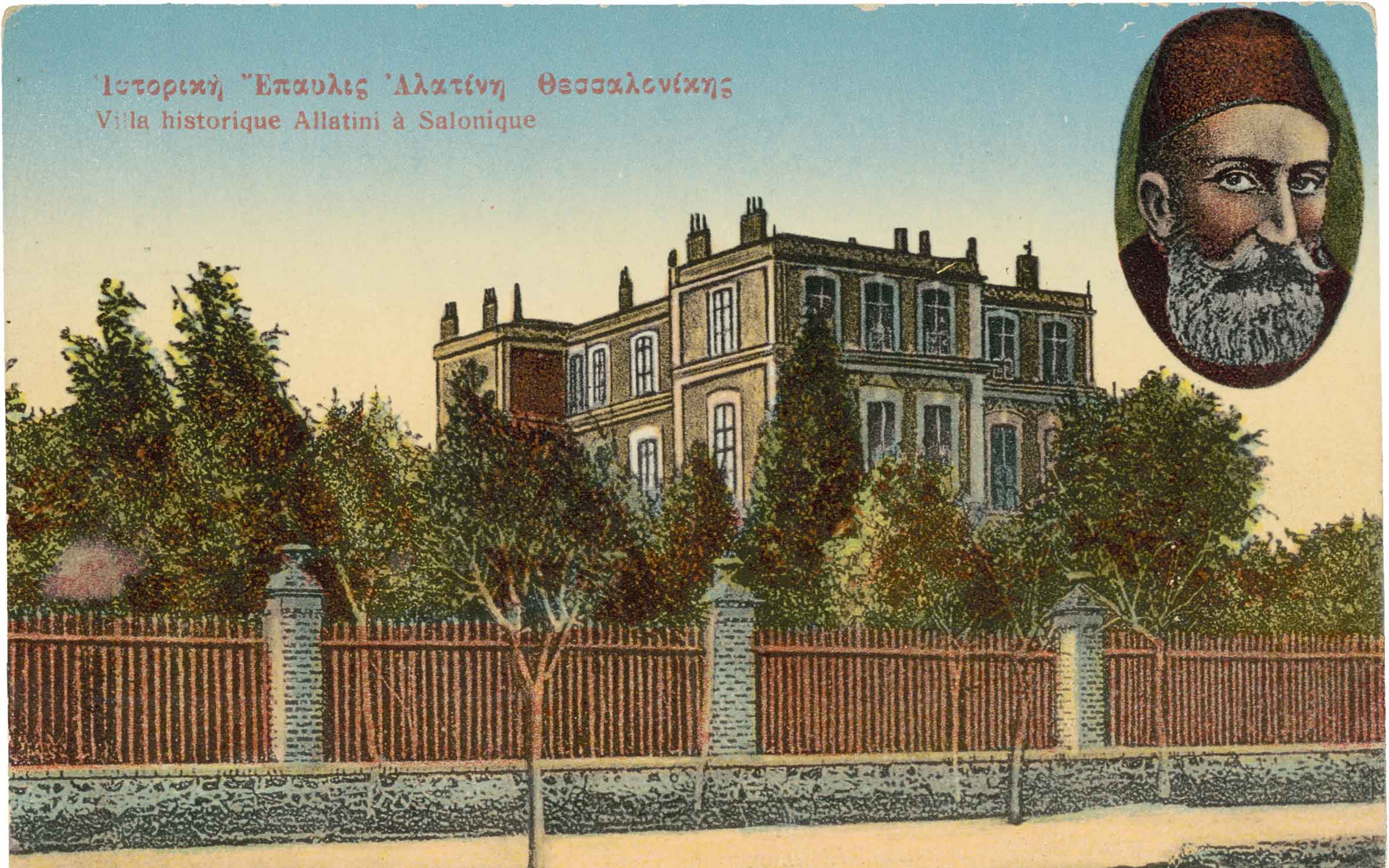

It was an elegant exile; his entourage included three sultanahs, two of his young sons, four eunuchs, and over a dozen servants. Thirty gendarmes on horseback escorted the party to the Hamidiye – the district named after him in the happier days of his reign. He was confined in splendor: with vast gardens and reception rooms that had once hosted formal balls for 700 guests, the Villa Allatini was the grandest in the city. Yet it wouldn’t quite do as it was; the former sultan insisted on the addition of a Turkish bath. It’s said he spent his days working on his carpentry and listening to his wives read the newspaper. His exile in Thessaloniki came to an end in 1912; before the Turks surrendered the city to the advancing Greek army, Abdul Hamid II was taken to Beylerbeyi Palace on the Bosporus to live out his remaining days.

Info

Villa Allatini: 198 Vasilissis Olgas

A Happy Ending

The cosmopolitan outlook of the upper classes of Thessaloniki didn’t extend to interfaith romance. So when, as the story has it, Aline Fernandez-Diaz fell into the arms of Spyros Aliberti on a rollicking tram ride in 1912, things ought not to have gone any further; Aline belonged to a prominent Jewish family whereas Spyros, curator of the Athens observatory and an officer in the Greek army posted to Thessaloniki, was a Christian. But destiny had its say. The couple eloped in Athens before returning to her family’s grand villa, the Casa Bianca, where they lived happily together for half a century.

Info

Casa Bianca: 182 Vasilissis Olgas

© Perikles Merakos

The Other Half

A tram – horse-drawn at first, and then electric-powered from 1908 on – once ran along the main boulevard in the Exoches area. The former tram depot, near the Villa Allatini, is the reason why the surrounding area is still called “Depot”. In the heart of this neighborhood is the charming Ouziel Complex. These 28 homes with their small gardens – commissioned by David Ouziel, a principal shareholder in the tram company – are truly villas in miniature, capturing the grace of their era in every detail.

Info

Ouziel Complex: Between Georgiou Papandreou and Cheronias streets

A Glorious Greek Victory

In 1912, during the First Balkan War, commander-in-chief Crown Prince Constantine led the Greek army into Thessaloniki. The surrender of the Turks was peaceful and dignified. But the victory was precarious; Greek forces had beaten the Bulgarian army to the coveted city by mere hours. Moreover, Greece lacked heartfelt support from the Great Powers, as members of the international community had enjoyed a privileged position under the Ottomans. In order to underscore Greece’s claim to Thessaloniki, King George I and his family moved from their palace in Athens to the newly liberated city. They resided in the Exoches area: Prince Nicholas, as the city’s military commander, at the Villa Mehmet Kapandji; King George I at the Villa Kleon Chatzilazarou (no longer standing); and other members of the royal family at the Villa Pericles Chatzilazarou.

Info

Villa Mehmet Kapandji: 108 Vasilissis Olgas

Villa Pericles Chatzilazarou: 131 Vasilissis Olgas

© Perikles Merakos

A Dark Day

King of the Hellenes for half a century, the much-loved George I was walking along the main boulevard in the Exoches when he was assassinated, shot in the heart by a madman, in March of 1913. The spot is marked by a bust of the king, joined more recently by a statue of his wife, Queen Olga.

The new Greek State had taken shape and flourished under George I. His reign brought significant territorial gains, as well as the inauguration of the Corinth Canal, the construction of the National Archaeological Museum, and the restoration of the Olympic Games. His successor’s reign, conversely, would be divisive: it was the eve of WWI, and Greece’s new king, Constantine I, was married to Kaiser Wilhelm’s sister.

Info

Bust of King George I, Statue of Queen Olga: At the cross street Aghia Triada, where Vasilissis Olgas turns into Vasileos Georgiou.

Intrigue at the Ball

The interlude between the first and second Balkan Wars was brief, and the peace was fragile. The alliance of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria against the Ottomans in the First Balkan War was a resounding success; the empire’s losses – Thessaloniki included – were substantial. But the alliance was an uneasy one; Bulgaria was dissatisfied with the division of the conquests. Anticipating aggression, Greece and Serbia entered into an alliance of their own. With tensions in the Balkans running high, discretion was key. A treaty was drafted. It remained only to bring the parties together without raising suspicion. The elegant solution: a ball at the Villa Mehmet Kapandji. The alliance, made on June 1st, 1913, came just in time; that same month, the Second Balkan war broke out, this time with Bulgaria in opposition to Greece.

© Perikles Merakos

“Lieber Tino…”

So began the telegram sent on March 4, 1915, from Kaiser Wilhelm II to his brother-in-law, King Constantine, advising him that the stability of his nation and his throne would best be served by Greece’s continued neutrality. Opinion in the Royal Family was divided; just days earlier, Prince George had sent a telegram to his brother urging support of the Allies.

Constantine, convinced that Germany was invincible, felt nothing was to be gained by opposing them. Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos believed there was everything to be gained: in supporting the Entente, Greece could obtain territories in Asia Minor, including Smyrna. Moreover, Serbia was under attack. Joining forces with the Entente had the twin advantages for Greece of honoring their alliance with Serbia and offering a potentially glorious outcome, a significant step towards the realization of the Great Idea, a revanchist dream of a Greater Greece encompassing ancient Greek lands.

The two parties soon reached an impasse. Venizelos resigned as Prime Minister and there followed an event known as the National Schism, with royalists centered in Athens, and the Provisional Government of National Defense, a parallel administration, and their followers active in Thessaloniki. Venizelos arrived in early October of 1916 to head a triumvirate formed with Admiral Kountouriotis and General Danglis. He stayed at the Villa Mehmet Kapandji, near the Triumvirate’s headquarters.

© Perikles Merakos

The National Schism

In an interesting twist of fate, the headquarters of the Triumvirate were at the Villa Modiano. The municipality had acquired the building after the city’s liberation, intending it for the use of the Royal Family. Now, it housed the king’s opposition. As the National Defense government prepared to join the Entente, Greece was bitterly divided, culminating in violent clashes in November of 1916 in Athens. In response to this, the Entente blockaded royalist ports until the following June.

King Constantine went into exile, leaving the throne to his son Alexander, and Venizelos returned to Athens. Meanwhile, Thessaloniki, long culturally diverse, was now truly international, hosting the hundreds of thousands of soldiers of the Armée d’Orient – troops from Britain, France, Serbia and as far away as India and colonial French Indochina.

Info

Villa Modiano: 68 Vasilissis Olgas

The Catastrophe in Asia Minor

Shortly after the Allied victory in WWI, the Greco-Turkish War began. By May of 1919, Greece had taken Smyrna and surrounding lands. The Treaty of Sèvres, which validated the claim a year later, proved to be, in the words of American diplomat Philip Marshall Brown, “as fragile as the porcelain of that name, though lacking its charm.” Turkey retaliated, and the 1922 Massacre of Smyrna was decisive; Greece ultimately did not get Asia Minor. Instead, Asia Minor came to Greece: under the Lausanne Convention, the population exchange brought approximately 1.3 million Christian refugees to Greece, far outnumbering the 585,000 Muslims who were compelled to leave the country for Turkey.

A large proportion of the Christian refugees arrived in Thessaloniki. They were housed in every available space, including the Villa Kapandji and the Geni Tzami. The shift in the city’s demographics that this resettlement caused was dramatic. Even as the Muslims departed, the city’s new Christian Greek residents brought some of the essence of Asia Minor back to Thessaloniki.

© Perikles Merakos

The Modern Exoches

In today’s Exoches, historic buildings are far outnumbered by modern apartment blocks, but the storied few that remain are central to the culture of the city.

The Villa Allatini (Vitaliano Poselli, 1898), once the elegant prison of Abdul Hamid II, is now a government building, while the Ouziel Complex (Jacques Moshé, 1925-1927) remains what it’s always been, a collection of charming private homes. The Casa Bianca (Pierro Arrigoni, 1912-13), home to Thessaloniki’s favorite love story, was rescued from near ruin and is now the splendid home of the Municipal Art Gallery, while the Cultural Foundation of the National Bank of Greece has beautifully restored the Villa of Mehmet Kapandji (Pierro Arrigoni, 1893). The Villa Modiano (Eli Modiano, 1906) is currently home to the Folk Life and Ethnological Museum of Macedonia and Thrace.

The Geni Tzami (Vitaliano Poselli, 1902), the mosque of the Ma’min community, housed the archaeological museum for years. It’s now a cultural space, under the auspices of the Municipal Art Gallery. The Exoches was a sociable district, and it still is: there are fine cafés in the gardens of the Villa Modiano and the Casa Bianca, as well as at the Epavli Marokkou by the Villa Chatzilazarou, and at the former Villa Michailidi, near the Geni Tzami. Belle Epoque glamour hasn’t vanished from the Exoches, and it’s doubtful that history has finished with this area yet, either.

Info

Epavli Marokkou (café/bar): 133 Vasilissis Olgas

Casablanca Social Club: 182 Vasilissis Olgas