The first thing you should know about sports training in ancient Greece is that it wasn’t for gym bunnies. The Greeks of the Classical era believed that physical fitness and mental clarity were two sides of the same coin. A good citizen was virtuous in mind and in body; training was a civic duty, rather than a lifestyle choice.

Training facilities and professional trainers were provided by the city – for ordinary citizens as well as for champion athletes. The biggest names in philosophy devoted extensive passages of their works to laying out the rules for proper training and healthy eating.

Athletic training, what we now know as “sports science,” was considered equal in status to medicine, while the “locker-room talk” of 5th c. BC Athens laid the foundations for Western political thought.

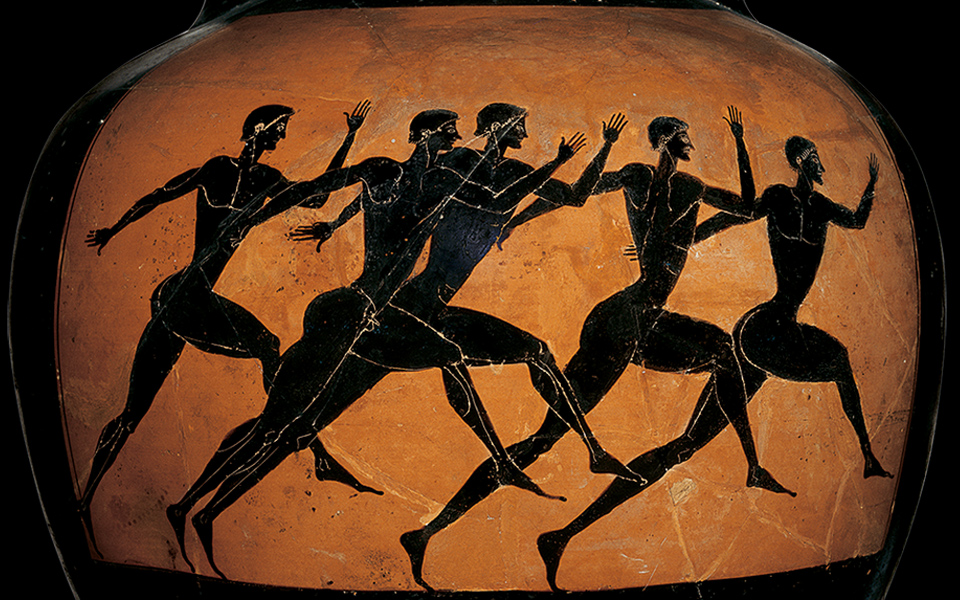

Nevertheless, there was little interest in fancy sporting gear or branded accessories. The gymnasium, now shortened to “gym,” derives its name from the word gymnos, meaning naked. But if you are put off by the idea of your wobbly bits being scrutinized by the opposite sex, fear not. In most places, physical exercise, like politics, was a male-only affair. The one notable exception was the city of Sparta, where both boys and girls were put through a militaristic boot camp from an early age.

Most ancient writers attribute the development of systematic training to the establishment of the Olympic Games in the 8th c. BC, which made the pursuit of sporting excellence one of the ties that bound the Greek world together.

Plato mentions several famous champions-turned-coaches and medics who pioneered the notion of a rules-based training regime as the foundation for sporting success.

© Hellenic Ministry Of Culture And Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund, National Archaeological Museum, Athens/Irene Miari

Hippocrates and Galen, best known for their contributions to medicine, observed athletes while they trained, in order to understand the human body, and developed anatomical and nutritional guides to improve performance.

Aristotle wrote detailed coaching manuals that were embedded in his philosophical works. By the 2nd c. AD, Philostratus was writing treatises devoted entirely to professional training regimes. The exchange between sport and science went both ways: Galen suggested that doctors must train like athletes to achieve excellence in their practice.

Philostratus wrote that systematic training evolved out of the more empirical methods that early Olympic athletes devised to improve their fitness. He describes (Gymnasticus, 44), somewhat imaginatively, how “they lifted weights, raced horses and hares, bent or straightened metal bars, pulled ploughs or carts, lifted bulls and wrestled lions, or swam in the sea so as to exercise their arms and their entire body. Their diet was natural, with whole grain bread and meat from oxen, bulls, goats and deer. They slept on hides or straw mattresses, and anointed themselves with plenty of olive oil. They were healthy and did not get sick easily. They stayed youthful into old age, and competed in many Olympics, some in eight and others in nine.” As sports pundits of any age always seem to maintain, he felt that no athlete of his day could hold a candle to the real champions of yore.

Part of the job of a professional trainer was to design a training regime, taking into account weather conditions, the psychological condition of the athlete, and any pre-existing injuries. There were then, as today, conflicting ideas on the best methods, rival coaching “schools” and sports fads. Galen expends a fair amount of time trashing, on medical grounds, the ideas of popular contemporary trainers.

A structured training regime in ancient Greece included three stages: warm-up, training and cool-down – much in line with current advice from the American Heart Association. However, there were also some extra elements which have not made it into present-day exercise routines.

The warm-up started with a massage, followed by gentle movements to boost blood flow and prepare the muscles for more intense exercise. What followed will be unfamiliar to modern exercisers: a rubdown with olive oil by a professional aleiptes. Oiling was an art because it played a critical role in sports such as wrestling, where a deft application could make it almost impossible for an opponent to perform a hold. To counteract the oiling, the athletes applied dust or sand. A wrestler would throw sand on their opponent tactically, with a view to covering those critical parts of the body that would receive their grip.

“Most impressive is that training was a total discipline, combining elements of biology, physiology, ergometry and sports medicine, and was fully integrated with philosophy and politics.”

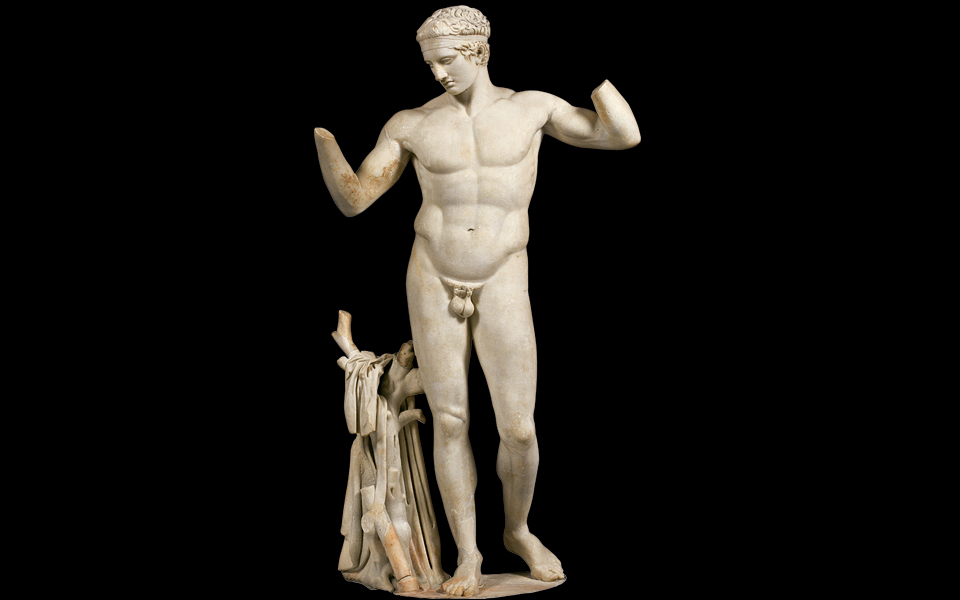

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund, National Archaeological Museum, Athens/J.Patrikianos

In the main workout, a range of options were available: total-body workout, zone workouts, or training geared toward competitive sport. Training could follow the same routine daily or rotate from day to day. There were specialized exercises for boxing, wrestling and the pankration – an ancient mix of martial arts that combined boxing and wrestling. Punching bags were used, as well as shadow-boxing techniques. Bends were used to strengthen the upper body. Various running exercises, including high-resistance running in sand, were employed to improve lower body fitness and aerobic performance. A variety of jumps are also described, while upper body strength was cultivated using rope climbing and other instruments. In addition to repetitive exercises, training also encompassed daily physical activities believed to enhance conditioning, such as digging, horse riding, walking, hunting and fishing. Galen rated most highly those activities that work a variety of muscle groups, including riding and swimming. He distinguished between high-impact and low-impact exercise, also mentioning the principle of circuits or interval training — where bursts of exercise alternate with short rest periods. He differentiated between general exercise and specialized training for professional athletes.

The duration of training sessions was at the discretion of the trainer and determined by the athlete’s physical condition. It continued for as long as the athlete retained a lively color, was able to move steadily and rhythmically, and kept “growing in bulk.” It was time to call it a day when the athlete became more sluggish and started falling to his knees to rest. Different forms of exercise were expected to yield different results on the athlete’s body. Running slimmed the body and inflated the muscles, due to its emphasis on breathing. Wrestling increased body heat, as well as the density and mass of muscles. The pankration was thought to dry out the flesh because it was more intense and shorter in duration. Lifting exercises and running were believed to cleanse the body from toxins through sweating.

The cool-down, or apotherapeia, was considered necessary for the body to return to its natural condition. It started with breathing exercises, which were said to relieve the heart. Next came the cleansing of the body from oil, sand and sweat. A metal strigil was used to scrape the skin; these special implements are found in excavations and depicted in vase paintings and sculptures. A post-workout massage followed, at the hands of a professional who used a variety of techniques described in some detail by Galen. Medical writers also praised the benefits of various types of baths − not only for cleaning but also for soothing tired muscles and inducing euphoria in the athlete: a kind of rejuvenating spa. Athletes took dips in natural springs and rivers, but also bathed in purpose-built facilities adjacent to the gymnasium. Baths could be hot or cold, and steam baths were also popular.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund, National Archaeological Museum, Athens/Irene Miari

When athletes were not training, they rested, as this was part of a total regime also calling for repose and sleep. Sunbathing was similarly recommended – not only to build endurance against the sun, and thus be able to perform in outdoor competitions, but also because solar rays were seen as beneficial to health.

An enormous body of knowledge went into sports training in Classical Greece, much of which remains in use today, or is being rediscovered. Most impressive is that training was a total discipline, combining elements of biology, physiology, ergometry and sports medicine, and was fully integrated with philosophy and politics. The results can be seen in the impressive physiques of ancient statues. Before getting too idealistic, however, it is worth remembering one more thing: if you look at Greek statues and think, “maintaining those abs must have been a full-time job,” you are not far off. Many citizens in ancient Athens were not expected to hold down jobs in the modern sense, as most labor was done by slaves and commerce carried out by resident aliens. When he was not at war or politicking in the agora, an Athenian man had all day to do pull-ups with Plato and sculpt his abs with Aristotle − he did not have to fit his workout into his lunch hour.