The Battle of Marathon, fought in August or September 490 BC, is widely regarded as one of the most significant events in ancient Greek history. The surprise victory of an 11,000-strong force of Athenians and their Boeotian allies, the Plataeans, over a much larger Persian host, played a pivotal role in the decades long conflict known as the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449 BC), immortalized in the epic work of Herodotos (c. 484-c. 425 BC), the “father of history,” and marked the start of the Golden Age of Athens.

The epoch making battle, fought on the coastal plain of Marathon, some 40km northeast of Athens, is best remembered today for two things: the enormous disparity in manpower between the two sides – the Persians outnumbering the Greeks by at least three-to-one – and the legend of the Athenian runner, Pheidippides, who collapsed and died of exhaustion after running from the battle site to Athens to announce the Greek victory – inspiring the creation of the modern long-distance race.

Today, visitors can explore this famous battle site, which is now a mix of marshland and pine forest, and walk around the two burial mounds of the Greek war dead, known as “tumuli,” located in serene parkland. The larger of the two mounds, the “Soros,” containing the cremated remains of the 192 Athenians who fell in the battle, dominates the surrounding landscape. Both monuments serve as a cenotaph, a tangible representation of the ancient Greek tradition of honoring and paying respect to those who sacrificed their lives in the defense of their city-state, and an enduring symbol of Greek resilience against a formidable external threat.

© Public domain

The Gathering Storm

The roots of the Battle of Marathon can be traced back to the start of the Ionian Revolt in 499 BC, an event that triggered the start of the Greco-Persian Wars. Several Greek city-states in the Ionian region of Asia Minor (present-day western Turkey), including Miletos and Ephesos, revolted against Persian rule. One by one, the cities ejected their Persian-appointed tyrant rulers, and declared themselves democracies. In doing so, the Ionian Greeks sought support from other Greek city-states from across the Aegean, primarily the mercantile city of Eretria, on the island of Evia, and Athens, one of the largest and most powerful cities in the Greek world.

Both Eretria and Athens, under the guidance of the experienced general Miltiades (c. 550-489 BC), chose to support the Ionian Revolt by sending a small force of ships and men to aid the Ionian rebels, which led to a direct confrontation with the Achaemenid Persian empire, then ruled by the ambitious and expansionist Darius the Great (c. 550-486 BC). Upon learning of their involvement in the revolt, including the burning of Sardis, the capital of the Persian satrapy of Lydia, Darius set his sights on punishing Athens and Eretria, with the ultimate goal of subjugating all of Greece.

In the summer of 490 BC, Darius sent an invasion force across the Aegean, which, according to Herodotus, consisted of 600 ships “packed with infantry.” Later Greek historians, including Plutarch and Pausanias, writing in the late 1st and 2nd centuries AD respectively, estimated the Persian host to have been around 300,000. Modern historians, on the other hand, put the figure at around 25,000-30,000 infantry and archers, with an additional force of 1,000 cavalry.

© Public domain

© Public domain

Superstitious Spartans

After sacking the city-state of Eretria, the Persian fleet, led by Artaphernes and Datis, sailed south to Marathon Bay in northeast Attica and established a beachhead on the adjacent plain.

Despite being hopelessly outnumbered, Miltiades, the most charismatic of Athens’ ten “strategoi” (generals), convinced the Assembly that passive defense was not the best strategy. Instead, he convinced his fellow citizens that an army of 10,000 hoplites, heavily armored infantrymen, drawn from the ten tribes or administrative divisions of the city, should march north to halt the Persian advance. Bolstered by an additional battalion of a thousand hoplites from the small city-state of Plataea, the combined Greek positioned themselves on the edge of the Plain of Marathon, preventing the Persians from moving inland.

As the two armies faced off, the Athenian commanders dispatched Pheidippides to Sparta to request urgent military support, a journey of 240km, which he completed in two days. He arrived as the deeply superstitious Spartans were celebrating the festival of Carneia, held in honor of Apollo Karneios, and received the unwelcome news that the army could not march before the full moon, still some days ahead.

The Athenians and their Plataean allies stood alone in the defense of Greece.

© Public domain

Men of Bronze

When forming up for battle, Miltiades knew that the Persians positioned their best troops in the center, including their much-feared archers, which were more maneuverable than the heavier Greek infantry, but no match in hand-to-hand combat. In order to succeed, he needed to avoid the Persian arrows and outflank their center. Taking his place in the line that day was a 35-year-old Aeschylus (c. 525/524-456 BC), who went on to win literary fame in Athens as a tragedian. His experiences in this and other battles inspired him to write “The Persians,” part of a now lost trilogy about the Greco-Persian Wars.

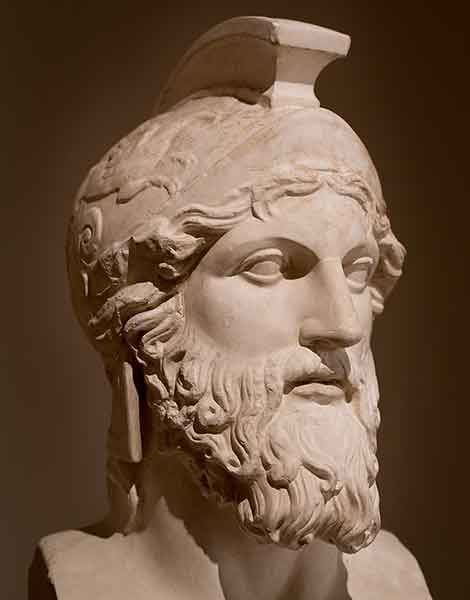

Phalanx formations of hoplites dominated the battlefields of the ancient Greek world, from the 8th/7th century BC to the rise of Rome, when new infantry units and tactics emerged. In stark contrast to their lightly armored Persian adversaries, Greek hoplites carried a large, bronze covered circular shield (“aspis”), wore bronze greaves on their lower legs (shin guards), and donned fully-enclosed Corinthian helmets for protection. Many wore a panoply of linothrax armor, a thick breastplate of linen, which, according to modern research, may have been thick enough to stop arrows fired from long range. In terms of weapons, hoplites carried a 2.5m-long spear and a short sword called a “xiphos,” or a forward-curving blade called a “kopis.” These short swords were especially useful in close quarters combat, when the lines of infantry broke rank.

© Public domain

To deal a decisive blow, Militiades extended his army along the whole length of the opposing Persian line but reinforced his two flanks, with the Plataeans on the left. Despite their heavy armor, the Greeks launched a lightening attack in close formation, quickly closing the gap of “eight stades,” a distance of approximately 1.5km, thus minimizing the time they would be exposed to the barrage of arrows. As they made contact, the weaker Greek center buckled, enabling the Persians to break through, but the Athenian and Plataean wings soon prevailed, encircling the Persian center. In disarray, the Persians stampeded back to their ships at the north end of the plain. In the panic and confusion, many were trampled, while others drowned in the nearby swamp.

The Athenians pursued the Persians back to their ships, and captured seven, at the cost of some of their bravest men, including Aeschylus’ brother, Cynaegirus. Herodotus records that “while taking hold there of the ornament at the stern of a ship, he had his hand cut off with an ax and fell; and many others also of the Athenians who were men of note were killed.”

The battle marked a stunning Greek triumph, boosting Athenian morale, and showcasing the effectiveness of hoplite warfare. It also put an end to the myth of Persian invincibility.

© Public domain

Honoring the Dead

In the immediate aftermath, the exhausted Athenians reorganized themselves and, believing their home city was still under threat, marched to Athens “as fast as their feet could carry them.” A detachment was left behind to bury their fallen comrades, which numbered 192 Athenians and 11 Plataeans. Herodotus records that 6,400 slain Persians were counted on the battlefield, a number which seemed enormous to the Greeks.

In Athens, the victory was celebrated as a major triumph and a source of immense pride. The hoplite warriors were hailed as heroes, and the battle became a symbol of Greek defiance against foreign invaders.

Three monuments were subsequently erected near the battle site: the Athenian tumulus (“Soros”), the Plataean tumulus, and a victory column, erected by the Athenians. What is unusual is that the Athenians traditionally buried their war dead in the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens. Instead, they interred their 192 fallen warriors in a massive, hemispherical mound, 12m high, evoking the burials of Homer’s mythical heroes in the “Iliad.”

Based on Herodotus’ account of the battle, historians believe the Soros marks the site where the charging Greeks encountered the barrage of Persian arrows. Writing in the 2nd century AD, Greek traveler and geographer, Pausanias, recorded that a large stele (stone slab), with the names of the fallen heroes, once adorned the monumental grave. A much smaller tumulus, 3m high and 15m in diameter, was erected for the fallen Plataeans.

© Public domain

© Public domain

Excavations

The Soros was excavated in 1884 by Greek archaeologist Dimitrios Philios, and again in 1890-1891 by Valerios Stais, who went on to become the director of the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. A large layer of ash was found inside, containing charred bone and oil phials, but no inhumations. The excavators concluded that the Athenians had cremated their dead and piled earth on top to create an enormous burial mound.

The area was revisited in 1970 by Spyridon Marinatos, the then Inspector General of Greek Antiquities. Marinatos and his team conducted a partial excavation of the burial trench inside the smaller Plataean tumulus, revealing five perfectly preserved skeletons, carefully placed side by side. Next to each skeleton was a tiny lekythos, a painted oil phial, as well as a large plate, for use in the afterlife. The skull of a sixth warrior was also found, bearing the marks of the spear or sword that likely killed him.

Speaking to the New York Times at the time of the discovery, Marinatos, said: “Many top foreign archeologists and historians believe that if the Persians—who, before Marathon, had conquered Eretria on the island of Euboea, a maritime power at that time—had won, and conquered Athens, whose civilization and culture were then beginning to flourish, Western civilization as we know it today, for better or for worse, could not have existed.”

He added: “The dead we found are the heroes of one battle that saved civilization.”

© Public domain

Archaeological Museum

Today, visitors can explore the two tumuli and pay a visit to the nearby Archaeological Museum of Marathon, which houses findings from the battle site and tumuli, as well as artifacts from the prehistoric cemeteries of Vrana and Tsepi, and the enigmatic 2nd century AD sanctuary of the Egyptian gods in Brexiza.

Open from 08.30-15.30 daily except Tuesdays, the museum is ideally visited after a guided walk around the archaeological site, including the two tumuli, a replica of the Victory Column, erected north of the Soros, a Mycenaean beehive “tholos” tomb, and the remains of an earlier Middle Helladic tumulus.