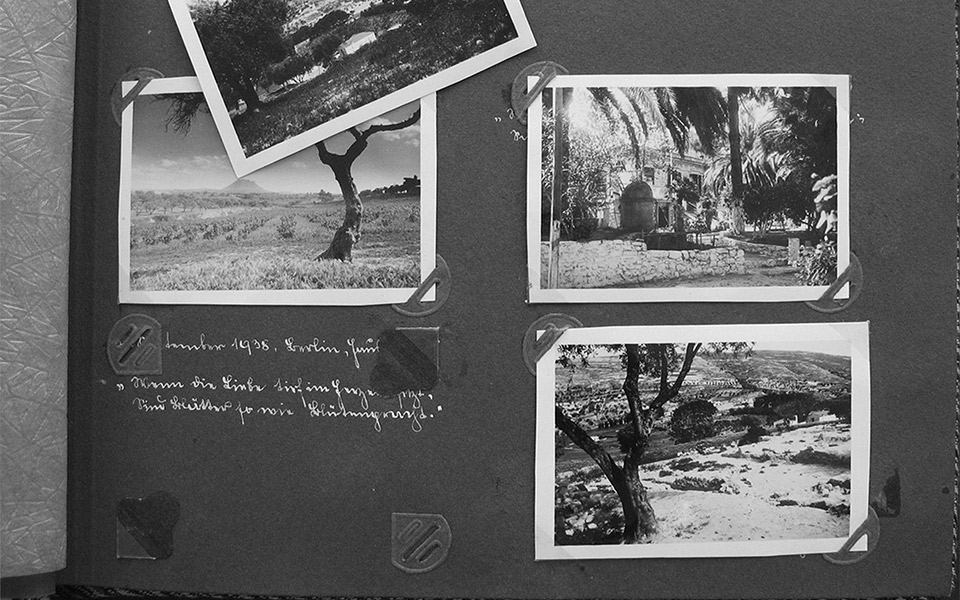

In 2010, Greek archaeologist Dr Georgia Flouda traveled to Austria in search of traces of Wehrmacht activity during World War II and its research on antiquities on occupied Crete. There, she met Gerlinde Schoergendorfer, widow of officer and archaeologist August Schoergendorfer, who worked for the occupying forces. Flouda was hoping Schoergendorfer would have been able to find her late husband’s excavation log, but instead she was given a photo album with 66 black-and-white images. With these, she was to reconstruct part of a turbulent era.

The pictures illustrated Schoergendorfer’s activities on the Greek island. Shortly before his arrival on Crete, dozens of antiquities had already been stolen by the infamous Austrian Major General Julius Ringel.

The research conducted by Flouda, who is curator of Prehistoric and Minoan Antiquities at the Archaeological Museum of Iraklio, recently returned to the fore thanks to an exhibition titled “Cretan Antiquities on Their Way Back” at the museum. Visitors were able to view a total of 34 ancient works taken from Knossos illegally during World War II. Twenty-six of those items were returned last November at the initiative of the University of Graz.

According to Flouda, the precise number of antiquities secreted out of the country by Ringel in a military plane has yet to be determined. Apart from the smaller objects he removed from the Stratigraphic Museum and the storehouse of the Villa Ariadne in Knossos, his obsession extended to larger items. Part of his loot was a headless Hellenistic statue that was sawn in two, the head of a male statue, a section of a sarcophagus with carved representations, a section of a stone burial slab featuring a depiction of a man, and a Minoan vessel carved from steatite.

Last November, on the occasion of the repatriation of objects Ringel had swiped, Kathimerini presented the heroic efforts of a former ephorate of antiquities in Crete, Nikolaos Platon, for the return of the objects.

One explanation for the systematic plunder of antiquities by the Austrian general may be his vanity. As Flouda wrote in her research, Ringel had met with Arnold Schober, professor of archaeology at the University of Graz, in 1941. Later, he would give Schober stolen objects as a gift, to create the “Cretan Collection.”

In her research, Flouda cites a passage from a letter by Schober, who was commenting on the prospect of cooperating with Ringel: “My institute has no ostracon from Crete and of course I did not want to let this favorable opportunity pass me by,” he wrote.

It was at this time that August Schoergendorfer, who was a scientific assistant at the University of Graz, arrived on Crete. From October 27 to December 12, 1941, he undertook the illicit excavations ordered by Ringel at a section of the Roman house, behind the Little Palace at Knossos, along with archaeologist Ulf Jantzen and the help of Greek prisoners.

By now, Schoergendorfer had been appointed Kunstschutz officer (a person in the German army responsible for “art protection”).

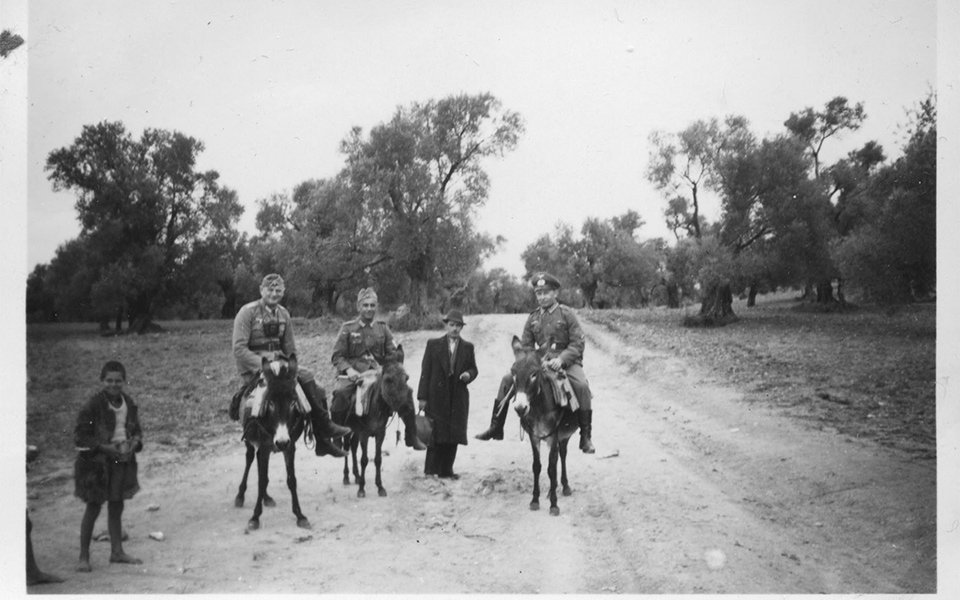

Studying dozens of photos in his album, Flouda documented Schoergendorfer’s archaeological itinerary on occupied Crete. The Austrian participated in surveys in the prefectures of Iraklio, Lasithi and Hania, and carried out excavations at two locations in the village of Apesokari, in Mesara. Flouda also discovered from unpublished reports by Platon that, unlike Ringel, Schoergendorfer handed the antiquities over to the Greek authorities. These findings have been the focus of Flouda’s study since 2009, as they form part of the Iraklio museum’s collection.

In Apesokari

Beyond the photographic documents, the researcher visited the village of Apesokari looking for witness accounts. “The house the archaeologist had requisitioned is still there, on the southern edge of the village,” she told K.

As Flouda mentions in a relevant study published in a British scientific journal, one of the photos in the album shows the family who lived in the house standing next to the soldiers of the Wehrmacht – most likely staged.

Flouda says the excavation at Apesokari may have also served as a cover for other purposes. On the southern coast of Crete, the Germans had set up outposts in a bid to catch any British soldiers landing on the island to help the Greek resistance. One of these outposts was adjacent to the excavation site.

Carefully examining each of the photo album’s 20 pages, she realized that they had been reused after finding notes in white ink dating to before 1941. At any rate, the owner of the album always carried it with him after the war.

This article was first published on ekathimerini.com