It is widely acknowledged that the traditional Greek diet is one of the healthiest in the world. Rich in fruits and vegetables, wholegrains, legumes, oily fish, and a moderate amount of animal protein – mainly from white cheese and yogurt – health experts agree that the Greek diet can lower your risk of cardiovascular disease and even improve your cognition. But how similar was the diet of the ancient Greeks? And was it just as healthy and balanced?

In many ways, the everyday eating habits of the ancient Greeks were quite similar to today’s Greeks. While a number of key ingredients used in the modern cuisine would have been absent from ancient kitchens, including tomatoes, peppers and potatoes, brought from the Americas after the 15th century, and rice from India and China, the diet was still largely based around the “Mediterranean triad” of cereals, olives and grapes, and leaned heavily towards the consumption of beans, lentils and nuts.

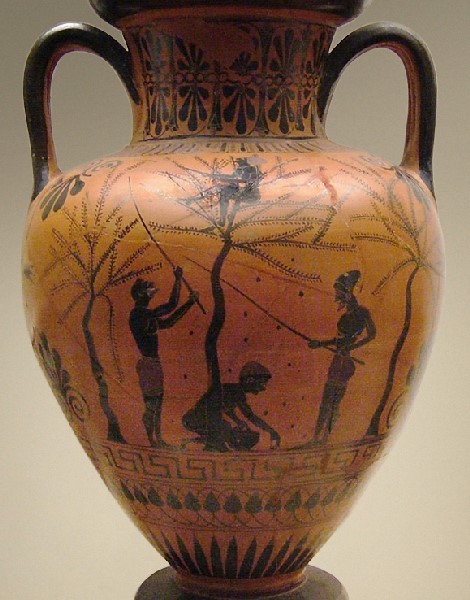

Following the rhythm of the seasons, scholars believe that up to 80 percent of the ancient Greek population would have been employed in agricultural work at any given time. Farmers harvested olives and grapes in the autumn months and cereals in the summer, and, depending on the availability of land, raised livestock (goats and sheep being the most common). But due to the relatively poor quality of the soil – described in ancient texts as “stringy” or “tight” – crop yields were low, which likely explains the rapid expansion of Greek colonialism from the 8th century BC onwards.

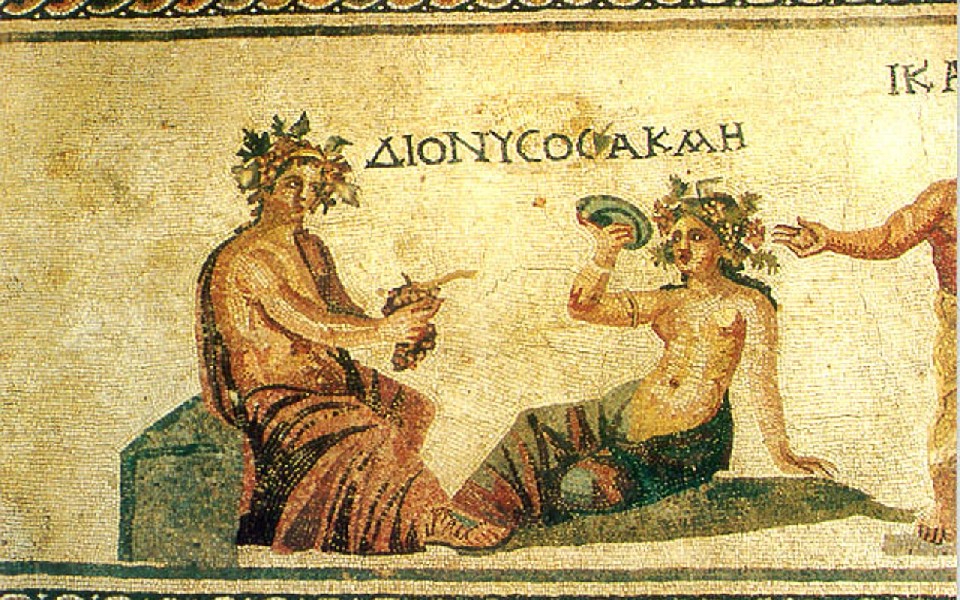

Whilst wealthy Greeks were able to afford elaborate meals and banquets (“symposia” – literally “gathering of drinkers”) that boasted a wide variety of ingredients, including finely selected and prepared meats, the diet of the average Greek would have been relatively simple and frugal.

The Mediterranean triad

Much like today, cereals formed the mainstay of the ancient diet. The two main grains were wheat and barley, baked into loaves or flatbreads, and, for special occasions and religious festivals, into cakes made with oats, chickpeas, sesame and honey. Today’s Christmas cookies, melomakarona, are thought to be derived from the ancient “makaria,” made from flour, olive oil and honey, and eaten at funerals.

Olives and olive oil were also important components of the everyday diet. Olive trees have been grown and harvested in Greece since at least the mid-4th millennium BC, likely earlier, and olive oil was traded across the length and breadth of the Mediterranean throughout antiquity. Besides food, olive oil was used in religious rituals, as fuel for lamps, and for medicinal and cosmetic purposes (Aristotle even recommended it as a form of birth control).

Wine was consumed throughout the day, from breakfast time to the evening meal, and was generally mixed with water. The best wines hailed from Thasos, Lesvos and Chios, and, like olive oil, was a widely traded commodity. The ancient Greeks also sweetened their wine with honey, and made therapeutic concoctions by adding thyme, pennyroyal, and other herbs.

Seafood was also widely consumed, much like today, including squid, octopus, cuttlefish, prawns and crayfish. Island and coastal communities had the best access to fresh fish, but sardines, anchovies and sprats (the cheapest) were oftentimes dried and salted and transported inland. Indeed, dried/salted fish was a cheap source of protein for poorer citizens throughout Greece. Other sources of animal protein included milk and cheese, from sheep and goat, and “oxygala,” an early ancestor of yogurt.

The consumption of meat was much less common than today (except for pork sausages). For many city-dwellers, roasted meat was only consumed at religious festivals and on special occasions. Fresh meat was prohibitively expensive – a piglet, for example, cost three drachmas, which was three days’ wages for a public servant – but for those in the countryside, wild fowl (quail, pheasants, mallards), hares, boar and deer would have been more readily available.

Breakfast, lunch and dinner, and a little light snacking

While modern nutritionists argue that the first meal of the day should be your biggest – “Breakfast like a king; lunch like a prince; dinner like a pauper” – the ancient Greeks believed the opposite was true. Breakfast (“akratisma”) was usually a very simple affair of barley bread, similar to today’s paximadi rusks, dipped in wine, and a side dish of figs or olives. Various sorts of pancake (“tiganites”) were also available, made with wheat flour, olive oil, honey, and curdled milk.

A light lunch (“ariston”) was taken around midday or early afternoon, consisting of salted fish, bread, cheese and olives, and selection of fruits (grapes/raisins, figs, apples, pears and plumes/prunes) and nuts (walnuts and almonds). Some opted for a light afternoon snack (“hesperisma”) of bread and olives and dried fruits.

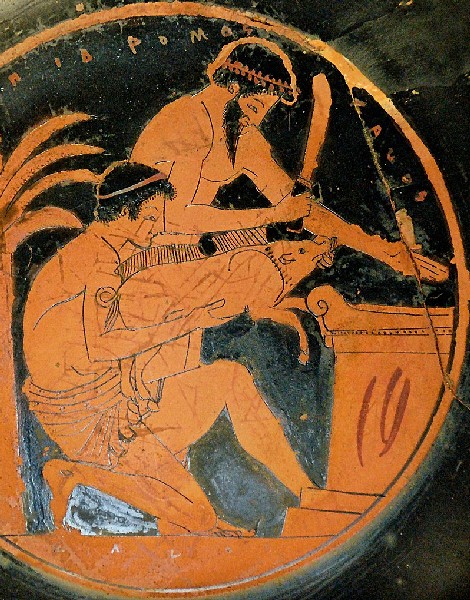

Dinner (“deipnon”), taken at nightfall, was the biggest and most important meal of the day. It was also the time when wealthier Greeks would host dinner parties with extended family and friends, although men and women frequently ate separately. “Meze-style” dishes included a selection of lentils, beans, chickpeas, peas and broad beans, as well as bread, cheese, olives, eggs, fruits and nuts. Fish would have been eaten, too, including sea bream, red mullet, sardines and eels.

Despite the paucity of fresh meat in the ancient Greek diet, pork sausages were nevertheless widely available and affordable to the urban poor. Soups would have also been a regular feature in the diet, made from lentils – the workman’s dish – beans and vegetables (onions, garlic, cabbage and turnips). The most famous soup from ancient Greek antiquity was the Spartan “Black Broth” (“melas zomos”), made with pork, salt, vinegar and blood.

Sweets and desserts were available, too, including “plakous” and “kortoplakous,” possible ancestors of baklava. Similar to the ancient Roman “placenta cake,” a honey-covered baked layered-dough dessert, kortoplakous was made of thin sheets of pastry, almonds, walnuts and honey.