Plaka embodies everything that is Athens. The neighborhood has been continuously inhabited since antiquity, so around nearly every corner you stumble across remnants of the ancient Greek, Roman or Ottoman empires.

The meandering, car-free streets boast some of the most charming neoclassical buildings in the city and wind their way whimsically up the slopes toward the Acropolis.

When the frenetic energy of the modern city gets me down, a slow stroll through the timeless streets of Plaka always serves as a reminder of why I fell in love with Athens, and why there’s no other city quite like it.

© Perikles Merakos

© Illustration: Philippos Avramides

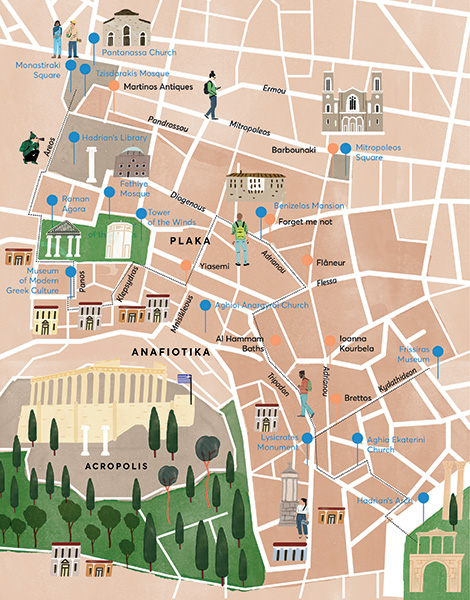

Let’s begin our wanderings at Monastiraki Square, where the Church of the Pantanassa and the Tzisdarakis Mosque stand guard over what has for centuries been a central meeting point and melting pot. Looking towards the Acropolis to guide us, we’ll walk up Areos Street, past the formidable columns of Hadrian’s Library on our left. Turning the corner, the ancient Gate of Athena Archegetis welcomes us to the Roman Agora, where historical eras rub shoulders with one another.

The Agora was constructed by the Romans between 19 and 11 BC. Walking clockwise around the former market complex, past the Roman columns, we’ll come to the Fethiye Mosque, built by the Ottomans in the 17th century, and the Tower of the Winds, built by the ancient Greeks from the same Pentelic marble as the Parthenon around 50 BC (although some sources suggest it dates to the second century BC). The octagonal tower is believed to be the oldest meteorological station in the world; it hosted a combination of sundials, a water clock and a wind vane.

© Perikles Merakos

Also known as the “neighborhood of the gods,” Plaka is built on what was once ancient Athens’ residential district, developing around the ruins of the Ancient Agora. The general area remained at the heart of the city throughout the Roman and Byzantine periods.

Following the arrival of the Ottomans in 1458, Plaka came to be the seat of the Turkish governor and known as the “Turkish quarter” of Athens. During the 1821-1829 Greek War of Independence, many of Plaka’s residents fled the battles that occurred there, and the area fell into decline.

After the newly installed Greek monarch, King Otto (1832-1862), chose to relocate the capital of the fledgling independent Greek state to Athens in 1834, however, Plaka experienced a resurgence.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

© Dimitris Vlaikos

A short walk up Panos Street from the Roman Agora takes you to the small neoclassical building housing the Museum of Modern Greek Culture. The “Man and Tools” exhibition here displays implements used in farming and small industry over the 200 years that preceded the onset of industrialization in Greece, in the 1950s.

A set of sickles caught my eye, made by “Uncle Yiannis,” an ironsmith from Korthi in Andros, who engraved a little bird on each of the sickles he made so that they would “sing” whenever the harvester used them.

Many of the items on display would have been familiar to the thousands of workers and craftspeople who flocked to this area from around Greece in the 19th century to help construct Otto’s new model capital city.

© Perikles Merakos

The top of Panos Street marks the upper limits of Plaka. From here, we could head east and explore the picturesque settlement of Anafiotika, built by stoneworkers who came here from the Cycladic island of Anafi. Instead, as soon as we pass the Old Temple of Athena, we’ll head back towards the center of Plaka, descending the narrow stone stairway onto Klepsydras Street and passing the cute little taverna and bookstall at the crossroads.

It’s magical passageways such as Klepsydras that make meandering through Plaka such a delight. Even after years of living in the city, each walk produces new discoveries: idyllic hidden corners, often with lush greenery overflowing from crumbling buildings, their rustic textures painted with colorful murals, and more often than not, an enticing little taverna lurking close by.

© Dimitris Vlaikos

My advice would be to ignore Google Maps and just get lost, so you can truly experience the wonders of these labyrinthine streets. But if you’re still reading, follow me past Mnisikleous Street, where you’ll see the crowded tables of the café Yiasemi spilling up and down the stairs.

The garden of the Church of Aghioi Anargyroi (Metochi of the Holy Sepulchre) is a verdant oasis of peace. The church is the first place to which the Holy Flame is brought from Jerusalem each Easter; witnessing the start of the Epitaphios procession here on Good Friday, or the celebration of the Resurrection at midnight of the following day, is an unforgettable experience.

© INTIME NEWS

From here, we’ll descend towards Diogenous Street, past the charming arts and craft stores such as the workshop of puppeteer and jeweler Alexis Papachatzis, and onto Adrianou, Plaka’s east-west thoroughfare lined with souvenir shops.

Walking eastwards, you’ll come across the Benizelos Mansion. Built in the first half of the 18th century, it’s the oldest house in Athens and a beautifully preserved example of how the privileged once lived.

Keep walking east towards the Frissiras Museum. Housed in a grand neoclassical townhouse, the museum was opened in 2000 by Vlassis Frissiras’ family; the Frissiras Foundation holds his vast collection of modern Greek and European painting. The museum hosts a regularly changing series of exhibitions, each usually focused around a specific theme.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

We’ll end up between Hadrian’s Arch and the Lysikrates Monument, at Aghia Ekaterini Church. You’ll be able to spot the location easily, as two enormous palm trees towering above time-worn columns mark the spot. The columns are the remains of an ancient temple dedicated to the goddess Artemis.

The church’s grand exterior is the result of 19th century renovations, which partly disguise an 11th-century Byzantine core – Athens’ oldest example of a cross-plan church with a central dome.

Sitting in the serene gardens outside, where many layers of history are literally laid on top of each other, you’ll find it the perfect place to reflect on our journey through Plaka, Athens’ very own time machine.