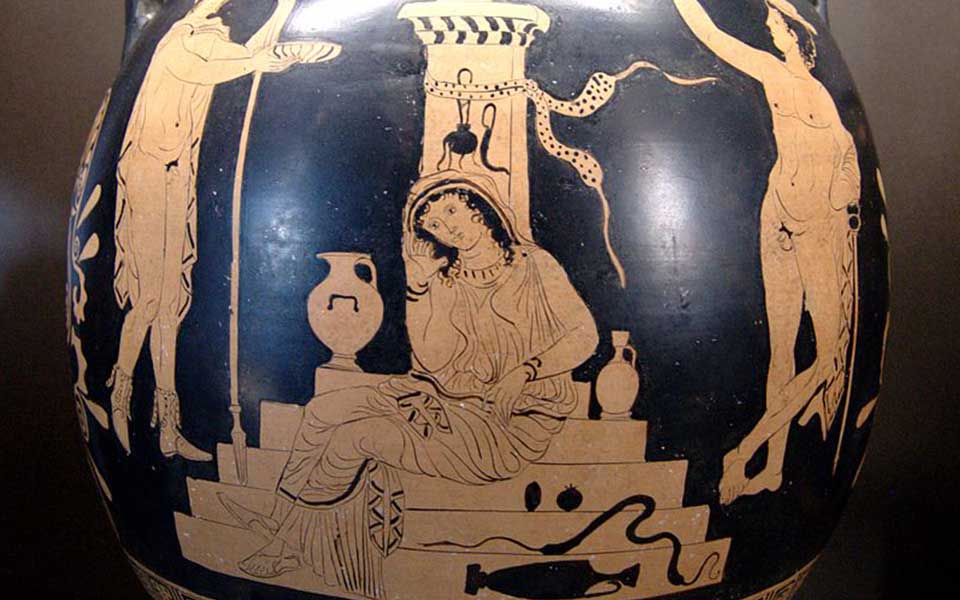

Atop the rocky heights overlooking the bay of Aulis on the coast of Boeotia, king Agamemnon looked down in horror at his young daughter, Iphigenia, bound and blindfolded on the sacrificial altar. It was here that he had assembled the Greek fleet before setting sail for Troy, but there was a problem: there was no wind.

Earlier, boastful of his prowess as a hunter, the king had committed the ultimate sacrilege by killing a deer in the sacred grove of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. As punishment she stopped the wind, preventing the fleet form embarking on their voyage across the Aegean.

© ArchaiOptix

In order to appease the goddess, the seer Calchas tells Agamemnon that he must sacrifice his eldest daughter. Only then would the winds turn.

In some versions of the myth, Artemis takes pity on the poor girl and, at the last minute, before she is sacrificed, replaces her with a deer and whisks her away to her sacred temple at Tauris on the far side of the Black Sea. In other versions, Iphigenia is sacrificed at the hands of her father, setting into motion a series of tragic, brutal and bloodthirsty events that, according to the 5th century BC tragedian and playwright Aeschylus, utterly destroy Agamemnon’s family, the doomed House of Atreus.

A mother scorned

Iphigenia’s sister, Electra, would come to play an important role in the torrid tale after her father returns from the 10-year war in Troy.

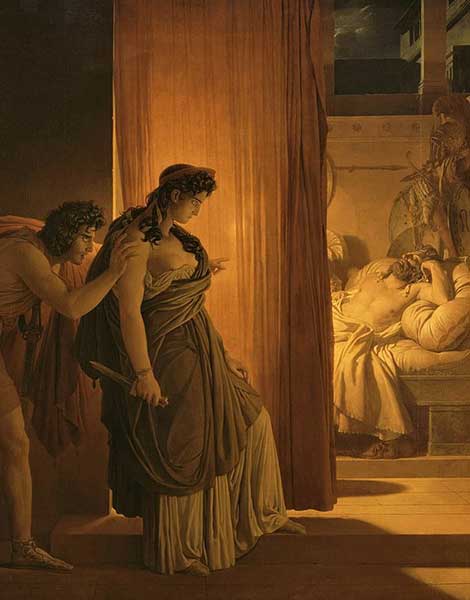

During Agamemnon’s long absence, his wife Clytemnestra, enraged by her daughter’s murder, had taken his cousin Aegisthus for a lover. Together, they plotted his demise and the take-over of Argos, the seat of Agamemnon’s kingdom.

When Agamemnon returned triumphant from Troy, he brought with him a war bride, Cassandra, the most beautiful of the daughters of King Priam of Troy. Cassandra had been given the power of prophecy by the god Apollo, but was then doomed to never to be believed because she refused him her love. In a later Roman tradition, the poet Virgil describes how she tried in vain to warn the Trojans against accepting the Greek gift of the Wooden Horse.

Presented with a double motive for revenge – grief and anger at the sacrifice of her daughter Iphigenia, jealousy at Agamemnon’s flagrant infidelity – Clytemnestra and Aegisthus murder him and his Trojan princess captive in cold blood. In Aeschylus’ particularly gruesome version of the myth, Clytemnestra entangles him in a cloth net while in the bath and butchers him with an axe.

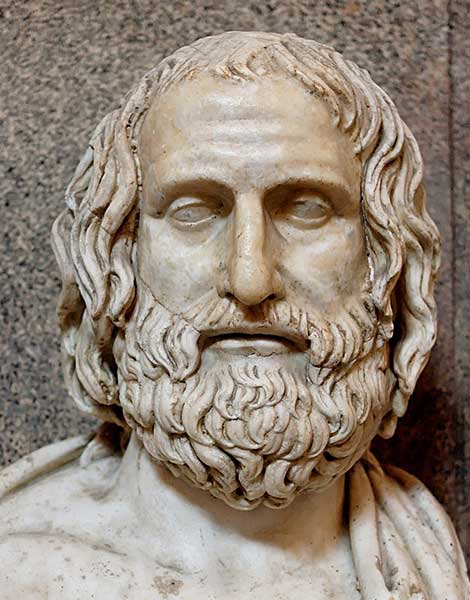

© Wind Group - Jastrow (2006)

Revenge in cold (but worthy) blood

Following the king’s death, Aegisthus assumes the throne and rules Argos with Clytemnestra as his queen for seven years. In the meantime, Agamemnon’s young son, Orestes, in mortal danger, has been smuggled out of the palace by his sister Electra, and raised by the king of Phoics, whose son, Pylades, becomes his close friend and companion.

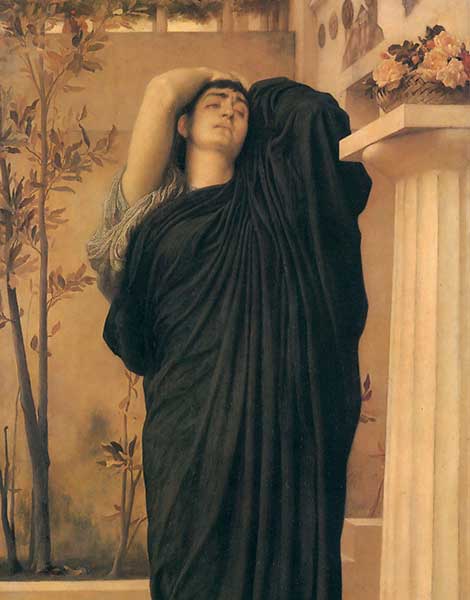

Distraught at the death of her father, Electra and her attendants secretly tend to Agamemnon’s grave – the background to the plot of the play “Libation Bearers,” the second part of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy.

Years later, as she is performing the sacred mourning rites at their father’s graveside, she recognises her brother Orestes returning to Argos with Pylades. Knowing her place in the social and heroic order, Electra encourages him to take vengeance for their father’s murder – “blood must match blood, and wrong with wrong.”

In Aeschylus’ play, this is as close to participating in the murder as she can get; the dirty work is left up to Orestes. In a bid to shock and appall their audiences, the later tragedians, Sophocles and Euripides, writing 40 years after Aeschylus, placed her front and center, in a much more active role.

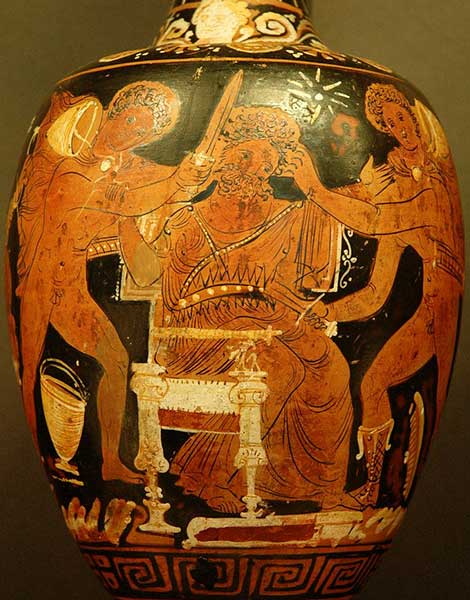

In the popular tradition, Orestes commits the double murder in the palace of Argos, both of his mother (matricide) and Aegisthus, the man sitting on his father’s royal throne. Despite performing a “praiseworthy act of vengeance,” as described in Homer, he is overcome by feelings of guilt and remorse and is pursued by the Furies, old chthonic deities whose duty it is to punish any violation of the ties of family piety.

He is relentlessly pursued by them to the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi where he is instructed to go to Athens to be tried in a fair and just court. In the homicide court of the Areopagus (next to the Acropolis), attended by the goddess Athena, he is tried and absolved of the crime – symbolic of the triumph of Athenian justice over blood-guilt and vengeance.

A playwright’s dream

The story of a sister and brother taking revenge on their mother for the murder of their father is bursting at the seams with dramatic content. Electra herself is a playwright’s dream: she has been wronged, she is bitter, wrathful, erudite, dangerous, righteous and, most terrifyingly of all for Greek audiences two and half thousand years ago, a woman.

All three Athenian tragedians of the 5th century BC, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, present her as fanatically hostile to her mother Clytemnestra, and certainly the main driving force behind her brother Orestes, but there are key differences in their portrayal. In Aeschylus’ version of the myth, Electra’s provocation and hostility is relatively passive, while Sophocles depicts her as more wilful, acting more like a lovelorn widow to her dead father than a respectful daughter going through the more dignified stages of mourning. To the ancient Greeks, this would have suggested incest – a recurring topic in Sophocles’ plays.

Euripides went even further, always seeking to provoke his audiences. His portrayal of Electra is nothing short of a femme fatale: forceful, calculating, and full of guile. She is obsessed with her hatred for her mother, her love for her father, but is nevertheless overcome by guilt and remorse. The impact on Athenian audiences would have have been shocking – yes, Orestes was the one who committed the murder but she was the real killer.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen

“Electra Complex”

The famous Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) proposed the psychoanalytic term “Electra complex”, earlier coined by Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875-1961), to describe a woman’s fixation on her father accompanied by a fierce resentment and jealousy of her mother. Inspired by Electra’s character, who plotted matricidal revenge against her mother, it is the counterpart to the “Oedipus complex”, which refers to a boy’s unconscious or repressed hostility towards his father as a rival for the affection of his mother.

Electra’s character has also been the subject of psychological treatment in the 1909 opera Elektra by Richard Strauss and Hugo von Hofmannsthal. In the retelling of the myth, the opera focuses on Electra’s furious lust for revenge, presenting a raw, brutal and violent horror.

On the modern stage, American playwright Eugene O’Neill presented a retelling of the Oresteia by Aeschylus in his 1931 play cycle “Mourning Becomes Electra.” Set in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the characters parallel characters from the ancient Greek plays. The play was later adapted into a film in 1947, starring Rosalind Russell and Michael Redgrave.

In film, perhaps the most famous production is the one by Greek-Cypriot director Michael Cacoyannis, famous for his Oscar-winning 1974 film “Zorba the Greek”, starring Anthony Quinn and Alan Bates. The first instalment of his “Greek tragedy” trilogy, Cacoyannis’ “Electra”, produced in 1962, is based on the play by Euripides. It starred Irene Papas in the lead role as Elektra, and Giannis Fertis as Orestes.