Delving into the annals of Greek antiquity unveils a tapestry woven with remarkable female figures whose indelible contributions often languish in the shadows of their male counterparts. These unsung heroines, despite the constraints of their era, navigated a complex web of societal norms to leave an enduring impact on politics, science, philosophy, and art.

From the formidable intellect of Hypatia, a pioneering mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher, to the influential political acumen of Olympias, Queen of Macedonia, these women defied convention to help shape the cultural landscape of ancient Greece.

Here, we shine a light on the endeavors of seven trailblazing Greek women, exploring the intricacies of their lives, achievements, and the challenges they overcame in a patriarchal society. By resurrecting their stories, we unravel a richer, more nuanced understanding of Greek history, celebrating the resilience and brilliance of these often-overlooked female luminaries.

© Shutterstock

© ArchaiOptix / Public domain

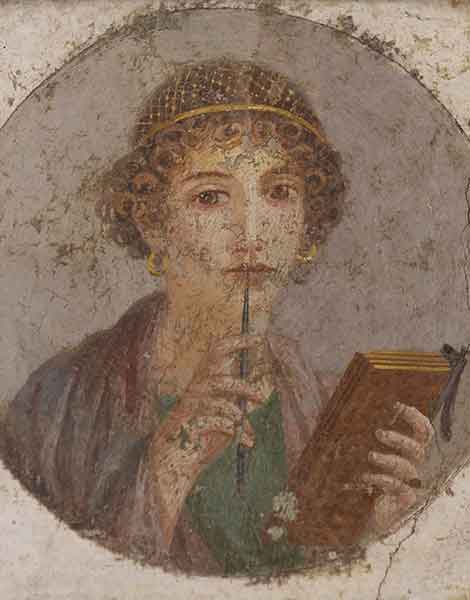

Sappho (c. late 7th century – 570 BC)

Sappho was a highly influential lyric poet from the Greek island of Lesvos, born sometime in the mid- to late 7th century BC (c. 630?). While much of her life remains shrouded in mystery, her impact on the world of poetry and ancient Greek culture is profound. She was widely praised by ancient writers, including the contemporary Athenian lawmaker and poet Solon (c. 630 – c. 560 BC), and philosopher Plato (c. 428/427 or 424/423 – 348 BC), who hailed her as the “Tenth Muse” or, more poignantly, “The Poetess.” Such was her fame, the scholars of Hellenistic Alexandria included Sappho in the canonical list of the Nine Lyric Poets, among those worthy of critical study.

Living during the middle Archaic Period (late 7th and early 6th centuries BC), Sappho’s poetry was both sensual and emotive. Surviving fragments – only around 650 lines, of which just one poem, the “Ode to Aphrodite,” is complete – show that she composed in the first-person, exploring themes of love, desire, beauty, motherhood, and domestic life. Her verses, which were likely accompanied by music and performed in public, also celebrated the complexities of human emotion and same-sex romantic relationships (the word “lesbian” is thought to come from Sappho’s birthplace Lesvos (“Lesbos” in English).

Sappho was associated with the creation of the lyric genre known as the “Sapphic stanza,” characterized by its unique meter and structure, and composed in the provincial Aeolic dialect of Lesvos and the adjacent Greek colonies of Asia Minor. Her work, while often intimate and personal, also delved into broader societal and philosophical themes, shining a light on the otherwise silent realm of womanhood in ancient Greece.

Sappho’s prominence extended beyond her literary prowess. It is widely believed that she was the head of a “thiasos,” a group of unmarried women dedicated to the cult of the goddess Aphrodite. Scholars suggest that she might have also taught young women in an educational setting, imparting her knowledge of poetry, music, and dance. The most famous tradition of Sappho’s tragic death claims that she committed suicide by leaping off the Leucadian cliffs (Cape Lefkada) into the Ionian Sea, due to unrequited love.

© Wilhelm von Kaulbach

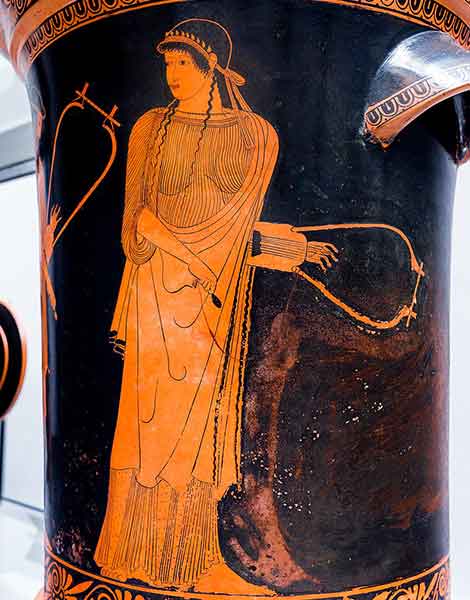

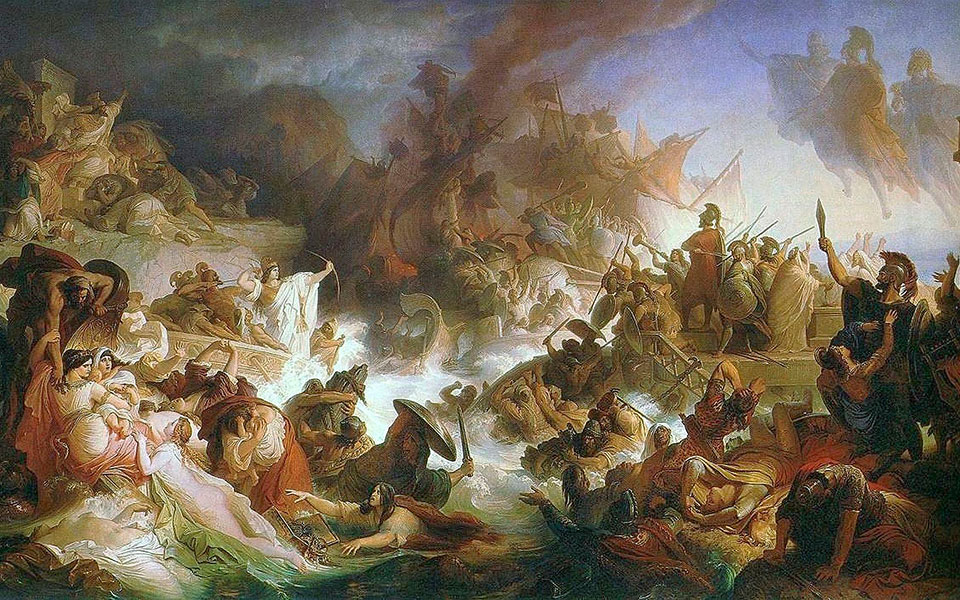

Artemisia I of Caria (5th century BC)

Named after the goddess Artemis, Artemisia I of Caria was a warrior-queen who ruled over the Greek city-state of Halicarnassus on the southwest coast of Asia Minor, present-day Turkey. Despite her Greek ethnicity, she played a prominent role during the Greco-Persian Wars of the early 5th century BC, fighting on the side of the invading Persians.

As a loyal subject of the Persian king Xerxes I, Artemisia commanded a contingent of five ships in the Persian fleet during the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC, a battle that would determine the fate of Greece and the nascent democracy of Athens. Her tactical awareness and bravery were recorded in Herodotus’s famous account of the Wars, published around 430 BC, earning her both respect and notoriety, especially in the eyes of the Athenians.

During the battle, Artemisia found herself trapped in the narrow strait between the floundering Persian fleet and an attacking Athenian ship (oared trireme). To evade capture, she made a strategic decision that showcased her guile. Instead of turning to engage the oncoming trireme, she deliberately attacked and sank a Persian ship, leading the pursuing Greeks to believe she was an ally. This maneuver not only saved her own fleet but also impressed king Xerxes with her skill and ingenuity.

Artemisia’s life and legacy challenge traditional gender roles, as she not only ruled independently for a time in Caria but also held a command position in the male-dominated realm of warfare. According to Herodotus, she convinced Xerxes to retreat to Asia Minor following the Greek victory at Salamis, advising him to leave his general Mardonius in charge of the army. (Mardonius suffered comprehensive defeat a year later at the Battle of Plataea). Little is known about her life after the war except that she was sent to Ephesus to look after Xerxes’ illegitimate sons.

Artemisia’s story offers a glimpse into the complexities of alliances and rivalries in Greek antiquity, emphasizing the agency and capability of women in historical narratives. Like Sappho, it is said that she leapt to her death from the Leucadian cliffs after her love for a man from Abydos (on the Hellespont) was unrequited.

© Nicolas-André Monsiau

Aspasia (c. 470 – after 428 BC)

A prominent and highly influential figure during the Golden Age of Athens in the 5th century BC, Aspasia was born in the Ionian-Greek city of Miletus, on the coast of western Asia Minor. While details of her early life are scarce, Aspasia’s significance lies in her close association with the famous Athenian statesman Pericles (c. 495-429 BC), with whom she had a son, Pericles the Younger (440s-406 BC).

Despite being a “metic” or resident foreigner, Aspasia went on to play a pivotal role in Athenian high society. She was known for her wit, charm, and sharp intellect, attracting the attention of scholars and statesmen alike, and was written about by comic dramatists, Athenian tragedians, and philosophers. Most modern biographies rely on the writings of 2nd century AD Greek historian Plutarch, who featured her in his account of the life of Pericles.

It is commonly believed that Aspasia worked as a “hetaira” (high-class courtesan) and/or a madam, managing a brothel. Some modern scholars, however, contend that she opened an academy for young women that became a popular salon, frequented by some of the most influential thinkers of the day, including Anaxagoras (c. 500 – c. 428 BC) and Socrates (c. 470-399 BC). Her ability to contribute meaningfully to these conversations would have been unusual for a woman at the time. In Athens, as in other city-states in the Greek world, women where often excluded from public life.

Whatever her status, Aspasia became independently wealthy and achieved a degree of notoriety, catching of the eye of the “strategos” (general) and up-and-coming statesman Pericles sometime in the mid-5th century. While little is known about her political influence, and whether they were officially married – some have argued she was his common law wife – Aspasia was undoubtedly a trusted advisor to Pericles, playing an important behind-the-scenes role in shaping his public persona.

Despite her accomplishments, Aspasia faced criticism and scrutiny due to her unconventional role, and, at one point, may have been put on trial for impiety. The comic playwright Aristophanes (c. 446 – c. 386 BC), among others, maligned her in satirical works, portraying her variously as a prostitute and a concubine. Nevertheless, her enduring influence on Greek intellectual life is acknowledged, with some considering her a symbol of the evolving status of women in early Athenian society.

© Fotogeniss / Public domain

Olympias (c. 375 – 316 BC)

Born around 375 BC, Olympias was a formidable and hugely influential figure in ancient Macedonian-Greek history. Known for her forceful personality and sharp intellect, and as the wife of Philip II of Macedon (382-336 BC) and mother of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), she hailed from the ruling Molossian dynasty of Epirus, which claimed descent from Neoptolemus (“new warrior”), son of the mythical hero Achilles.

Olympias married Philip in 357 BC, sealing a strategic alliance between the Molossians and Macedonians. During Philip’s reign, she attracted intrigue as his queen consort by meddling in complex power struggles within the Macedonian court, and was seen by some as a political threat. A passionate devotee of the mystical cult of Dionysus, Olympias’ religious fervor and rumored involvement in strange, esoteric rituals added to her enigmatic reputation.

In 336 BC, tragedy struck when Philip was assassinated at Aigai, capital of the Macedonian kingdom. Some historians have claimed that Olympias was in on the plot to remove her husband. Either way, she was catapulted into a precarious situation. With her 20-year-old son Alexander now on the throne, she faced opposition from rival factions. Her ruthless determination to protect Alexander’s position led to the elimination of potential threats, including political adversaries and other members of the royal family. Most shocking of all, several ancient sources, including 2nd century AD Greek writer Pausanias, report that Olympias oversaw the murder of at least two of Philip’s other children by later marriages: Europa, a girl, and Caranus, a teenage boy.

Olympias’ influence also extended into the military campaigns of her son, who embarked on an invasion of the Achaemenid Persian empire in 334 BC with an army of over 50,000 men. She corresponded with him regularly, offering advice and strategic counsel. However, as Alexander’s conquests expanded, their relationship strained, and Olympias faced political isolation after her son’s marriage to Roxana, a Bactrian princess, in 327 BC.

After Alexander’s untimely death in 323 BC, Olympias continued to navigate the turbulent waters of Macedonian politics. However, the subsequent Wars of the Diadochi (Alexander’s successors) led to her capture by Cassander, resulting in her execution in 316 BC (some sources report that she was stoned to death by the families of her victims).

Olympias’ legacy is complex, reflecting both her political acumen and ruthless ambition. As the mother of one of history’s greatest conquerors, her influence reverberated through the Hellenistic period.

© Jean-Léon Gérôme

Phryne (c. 371 – after 316 BC)

Phryne, a celebrated hetaira (courtesan) from Thespiae in Boeotia, was renowned for beauty and wit. Little is known about her early life except that she was born sometime around 371 BC, at the beginning of the short-lived Theban hegemony (371-362 BC), and grew up in a poor household. Ancient historians claim that her real name was “Mnesarete,” and that the term “Phryne” (meaning “toad”) was used on account of her yellowish complexion. Despite her lowly birth, she spent the majority of her adulthood in Athens, the intellectual and artistic hub of the Greek world, where she became one of the wealthiest women of the age.

Phryne’s physical beauty was renowned, making her a subject of admiration and artistic inspiration. She famously posed for two of the greatest artists of Classical Greece, Praxiteles and Apelles, which contributed to her elevated status in Athenian society. It is alleged that Phryne modelled for Praxiteles’ most famous statue, the “Aphrodite of Knidos,” one of the first three-dimensional and life-sized statues of a female nude in ancient Greek art.

One of the most famous anecdotes about Phryne involves her daring trial for impiety, which took place shortly after 350BC. Accused of “asebeia” (blasphemy) by a former lover profaning the Eleusinian Mysteries, she was defended by the orator Hypereides (c. 390-322 BC), one of Athens’ most gifted logographers. In a dramatic courtroom moment, he bared her naked body to the jury, supposedly swaying them with her beauty and leading to her acquittal.

Phryne managed to accrue considerable wealth during her lifetime. According to one source, when Alexander the Great famously razed the city of Thebes in 335 BC, as punishment for rising up against Macedonian rule, she offered to pay to rebuild the walls, on condition that the words “destroyed by Alexander, restored by Phryne the courtesan” were inscribed upon them.

Phryne’s legacy extends beyond her physical allure and legal drama. While historical details about her life may be scarce, she symbolizes the blurred lines between social classes in ancient Greece and challenges stereotypes about the limited agency of hetairai.

© Shutterstock

Cleopatra VII (69/70-30 BC)

Cleopatra VII, born in Alexandria in 69 or 70 BC, is arguably one of history’s most captivating figures. The last pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the final ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, she was a direct descendent of the first Ptolemy (c. 367-282 BC), a Macedonian-Greek general who served as one of Alexander the Great’s bodyguard companions.

Cleopatra’s tumultuous life, which has served as inspiration for numerous cultural depictions over the centuries, was marked by political intrigue, strategic alliances, and legendary romances with two Roman leaders, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

Cleopatra ascended to the throne at the age of 18, inheriting a kingdom in turmoil. Her intelligence and charisma quickly came to the fore, as she sought to quell internal strife and establish diplomatic relations with the Roman Republic, the most powerful military and political faction in the Mediterranean world. To that end, the Greek writer Plutarch implies that Cleopatra spoke multiple languages, including her native Koine Greek, Egyptian (she was the only Ptolemaic ruler to be conversant in the language), Ethiopian, Aramaic, Arabic, Parthian, and Latin, although her diplomatic dealings with the Romans would have been conducted in Greek.

One of the most notable aspects of Cleopatra’s life was her relationships with Caesar and Antony. Her affair with Caesar, who visited Egypt in 48 BC and with whom she had a son, Caesarion (“Little Caesar”), solidified her political position as a client queen. According to a famous passage in Plutarch on the life of Caesar, she was wrapped inside a bed sack and smuggled into the palace at Alexandria to meet the Roman statesman in secret. She later traveled to Rome in 46 BC, where she resided at Caesar’s villa, causing dismay among the Roman senatorial class. Following Caesar’s infamous assassination in 44 BC, Cleopatra returned to Egypt, and declared her three-year-old son as her co-ruler, Ptolemy XV.

Cleopatra’s subsequent relationship with Mark Antony further intertwined Egyptian and Roman affairs. They formed a powerful alliance and had three children together. However, their union faced opposition in Rome, contributing to the tensions that led to the famous naval Battle of Actium in 31 BC, fought off the west coast of Greece. Following Antony and Cleopatra’s defeat by Octavian (later emperor Augustus), the lovers famously took their lives in 30 BC.

Cleopatra’s legacy is multifaceted. Her ability to navigate the complex power dynamics of the time showcased her as a shrewd leader. Additionally, her romances with Caesar and Antony have solidified her place in history and popular culture, inspiring countless works of literature, art, and film.

© Louis Figuier

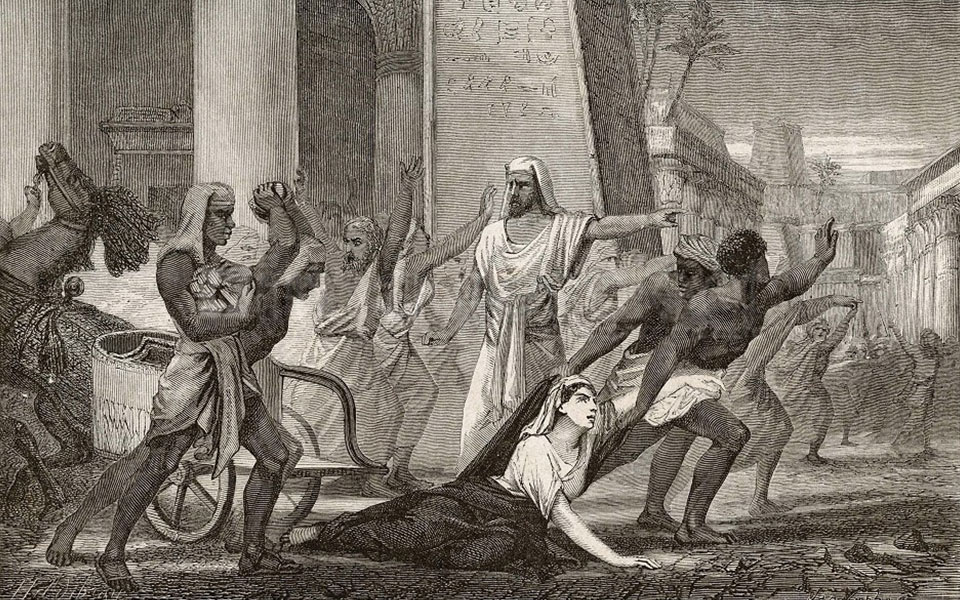

Hypatia (c. 350-370 – 415 AD)

Hypatia, born around 360 AD in Alexandria, Egypt, was a prominent Neoplatonist mathematician, philosopher, and astronomer during the late Roman period. As the daughter of the mathematician Theon of Alexandria (c. 335 – c. 405 AD), Hypatia received a comprehensive education at the highly prestigious “Mouseion” school, where her father was head teacher. She is the first female mathematician in history whose life is well recorded in contemporary texts.

Hypatia became the head of the Neoplatonic school in Alexandria, a position typically held by male scholars. Her lectures and writings covered a broad range of subjects, including geometry, algebra, astronomy, and philosophy. She contributed significantly to the understanding of conic sections and authored commentaries on works by influential Alexandrian mathematicians like Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100 – c. 170 AD) and Diophantus (3rd century AD). She also built astrolabes, used for charting the course of celestial bodies in the night sky.

Tragically, Hypatia’s life was cut short in 415 AD during a period of religious and political turmoil. Her association with the Neoplatonic tradition made her a target for Christian fanatics, who were intolerant of her pagan beliefs. A mob, reportedly aligned with Cyril, the Bishop of Alexandria, attacked Hypatia, leading to her brutal murder.

Stripped naked and violently tortured with “ostraka” (sharp roof tiles or oyster shells), Hypatia was then beaten to death, her limbs torn from her body and dragged through the city. Contemporary Greek Christian church historian Socrates Scholasticus (c. 380 – after 439 AD), author of the “Historia Ecclesiastica” (Church History), condemned the savage killing, declaring, “Surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort.”

Described as a universal genius, Hypatia transcended societal expectations, engaging in public life and contributing to philosophical and scientific discussions at a time when women faced substantial limitations. Her teachings influenced generations of scholars, and her tragic end became a symbol of the clash between reason and religious extremism.

Despite the loss of many of Hyaptia’s written works over time, the fragments and descriptions that remain offer a glimpse into the brilliance of a woman who defied societal norms and became a beacon of knowledge and inspiration in the ancient world.